Under the direction of Johannes Leitz, Weingut Josef Leitz has earned the reputation of being one of Rheingau’s top growers and moreover, one of the finest producers in Germany. Since taking over his family estate in 1985, Johannes has grown his holdings from 2.6 hectares to over 40, most of which are Grand Cru sites on the slopes of the Rüdesheimer Berg. Once the home of some of the world’s most sought after and expensive wines, the region fell to mediocrity in the years following the Second World War. Josi has made it his life’s work to reclaim the intrinsic quality of his native terroir and introduce the world to the true potential of the Rheingau.

The Rheingau is a small region, stretching only 20 miles from east to west. It is marked by a course change in the Rhein River’s flow to the North Sea from its origins in the Swiss Alps. As the Rhein flows north along the eastern edge of the Pfalz and Rheinhessen, it runs directly into the Taunus Mountain range which has a subsoil comprised of pure crystalline quartzite. Rivers, no matter how mighty, are lazy and the Rhine has yet to break through the quartz infrastructure surrounding the town of Mainz. At Mainz, the Rhein turns west and the 30 km stretch between Mainz and Rüdesheim makes up the majority of the Rheingau. Even though the region is further north than the middle Mosel, its south facing slopes get hotter than the narrow Mosel Valley which therefore provides important diurnal temperature variation.

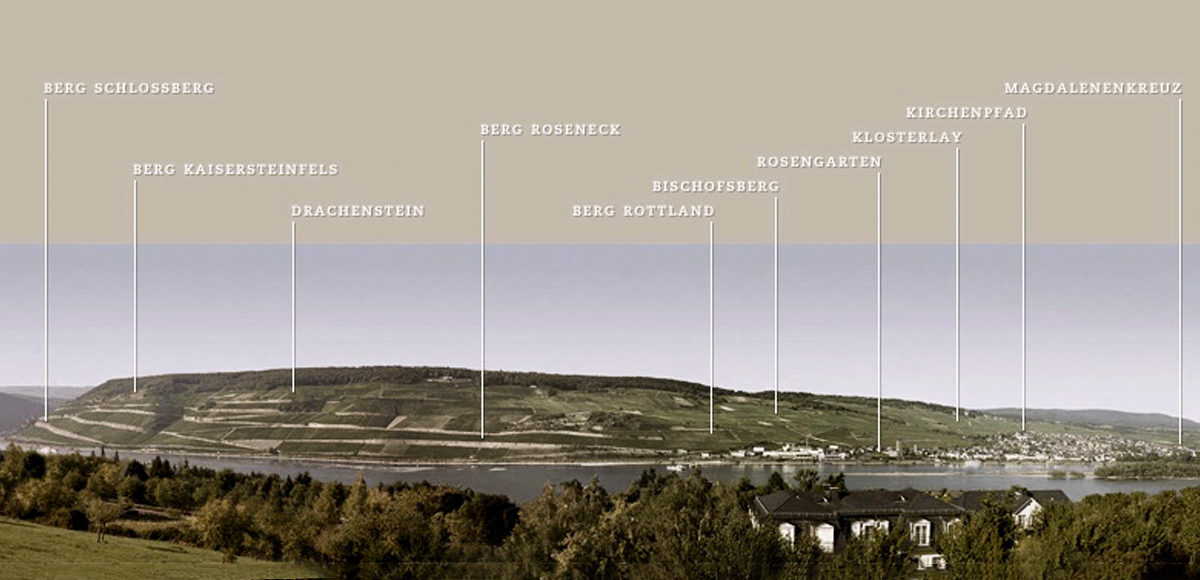

Leitz’s estate vineyards lie entirely on the westernmost part of the Rheingau on the Rüdesheimer Berg—a steep, south-facing hillside of extremely old slate and quartzite—planted entirely to riesling, encompassing the Grand Crus of Schlossberg, Rottland, and Roseneck. Leitz trains his vines in a single-cane, cordon system to improve the quality and character of the fruit, differing from the majority of Rheingau growers where the practice has long been to prioritize yield via a double-cane system. Johannes is a firm believer that the crucial work of the vigneron takes place in the vineyards. Focused on farming as sustainably as possible and working by hand, the grueling hours of labor on the ultra-steep slopes allow these ancient vineyards to reach their maximum potential.

After harvest, Josi is equally focused on working gently in the press house and ageing the wines on their gross lees. Johannes selects bottle closures to reflect, and more crucially serve, the individual cellar practices employed for each wine; Stelvin closures are used for wines raised in stainless steel to preserve freshness while wines raised in cask are bottled under cork to allow for a long development in the cellar.

With the 2011 vintage, Leitz began to designate the pre-1971 parcel names on select bottlings, reviving the individual voices of “Hinterhaus” (Rottland), “Ehrenfels” (Schlossberg), and “Katerloch” (Roseneck). He has also resurrected the once neglected site of Kaisersteinfels, which has become one of the most sought-after wines of the Rheingau. “Der Kaiser” sits high, just beneath the forest line of the Rüdesheimer-Berg, with a spectacular view overlooking the confluence of the Nahe and Rhein Rivers. The singular terroir on the westernmost point of the Rheingau is composed of quartzite, very old grey slate, as well as some iron-rich red slate and produces wines with incredible complexity and length.

In 2011 Johannes was recognized by the esteemed Gault Millau as “Winemaker of the Year.” We could not be more excited to be a small part of the Leitz project. We believe that these are some of the finest white wines in the world.