“Less is more.

Stay close to your vines.

Never think you know it all.

Nature decides.” — Nathalie Vignier and Sebastian Nickel

A domaine of “hidden treasures”

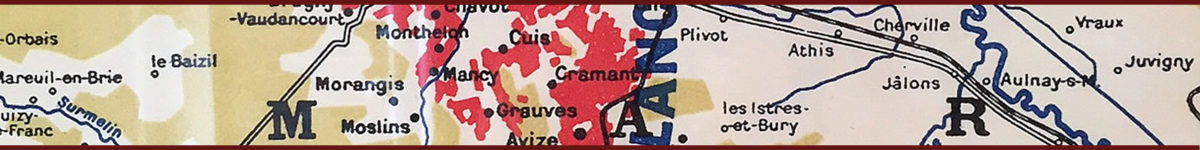

The Vignier family history in Champagne dates to 1530, the time of Nicolas Vignier of Bars sur Seine. Nicolas was a physician, lawyer, theologian, and court historian for Henry III. His descendant, Nathalie Vignier, is now the tenth generation to pursue viticulture and winemaking in Champagne, and the sixth generation to do so in the grand cru village of Cramant, in the Côte des Blancs.

In the early 20th century, Nathalie’s grandfather, Paul LeBrun, had two hectares, taken over from his father, Henri LeBrun. Paul resolved to become an independent vigneron by separating himself from the big négociants after World War I and was among the first to do so in the Côte des Blancs. He established Champagne Paul LeBrun in the 1930s. Frank Schoonmaker — a long-time collaborator with Alexis Lichene in the wine trade, and together two of the most influential figures in shaping American views on European wine in the last century — was the first to import the wines to the U.S.

Nathalie and her brother, Jean, took over the domaine from their parents 12 years ago, with Jean on the business side and Nathalie in the vineyards and cellar. Nathalie’s husband Hubert Soreau (another Schatzi!) is the winemaker at Le Clos l’Abbé in Epernay. Through him, Nathalie and close family friend Sebastian Nickel (whose grandmother’s family farmed land around Sézanne and held plots that became AOC Champagne in the 1960s) made the connections that enabled them to realize a shared vision and dream — one with roots in Nathalie’s father’s profound understanding of the land. He had always told them there were “hidden treasures” in the 16.5 hectares of chardonnay in Côte des Blancs and Côte de Sézanne that constitute the Vignier LeBrun vineyards.

The epiphany

In 2006, Nathalie and Sebastian began their hunt for those treasures, sampling berries before harvest, tasting wines after fermentation, working through small batches of old wines in the cellar. They realized Nathalie’s father was right. That epiphany compelled them to try making a small range of wines from a narrow selection of plots around Cramant, Chouilly, and Oiry, as well as in the Sézannais — all, Sebastian says, “showing a strong personality.”

“The first fruits for the future of J. Vignier were picked in 2007 and 2008 (a fantastic vintage!),” Sebastian explains. “At that time, we did not know that it would lead us to a totally new approach to winemaking and viticulture. We just picked and fermented some selected vineyards separately to see what it would look like.” Since then, Nathalie and Sebastian have been gradually aligning the domaine to their shared philosophy: farming without herbicides or pesticides, focusing on small production, single parcel wines of higher ripeness and extraordinarily long lees aging (up to 12 years), and a foreseeable return of oak to the cellar.

A shared vision

Nathalie says she realized as a child that she wanted to be a winemaker, but the impetus was not wine itself. “I was impressed to hear people talking a foreign language at my grandparent’s place, so I wanted to work abroad. After my studies, I found a training period in Germany and England. During holidays, I came back to help my parents in the winery and vineyards. Finally, I said to myself: This is what I really want to do! Not paperwork, but growing vines, making wine, and selling what we have made. In 1994, my father asked me to come back.” Nathalie did go to business school and worked for a time as the chief agricultural expert for insurance companies, specializing in hail and frost damage to vines. This put her in touch with a range of growers in both Champagne and Burgundy.

Sebastian brings an outside perspective. He’s German and grew up in the Netherlands and Germany. He studied biology, and, crucially, spent a year at the INRA (the French equivalent of the USDA) in Dijon, where his lab was so close to Gevrey-Chambertin, he fell under its spell. Soon he changed course to study winemaking and enology, then went on to work in vineyards and cellars in the Languedoc, Minervois, and Australia.

Nathalie and Sebastian now collaborate closely on the J. Vignier wines. All decisions about blending, dosage, and vineyard selections are shared. Sebastian says he and Nathalie are guided by a deep respect for both the long tradition and the future potential of the domaine, as well as the work and wines of Mignon, Agrapart, Laherte, Dehours, Jacquesson, among others. “But wines and growers from other regions also inspire us. We all love the northern Rhône, Burgundy, Barolo, Gigondas, Malbec from Cahors, and German riesling, of course!”

Wines of two côtes

Many of the small grower-producers who work within Champagne are in the Côte des Blancs, where the big houses traditionally have owned fewer vineyards. Planted between 1950 and 2010, the Vignier vineyards are deeply rooted in the chalky slopes of the grand cru villages of Cramant, Oiry and Chouilly. Nathalie’s family also own parcels in the warmer Côte de Sézanne, about 50 km to south, where Nathalie’s family has been acquiring plots for several decades.

Côte des Blancs

Cramant and Avize constitute what Peter Liem calls “the historical heart of the Côte de Blancs,” noting that these were the first villages of the area to be classified grand cru. The chalky clay soils of Cramant give a richness and power that past winemakers blended with the comparatively spare wines of Le Mesnil-sur-Oger for balance. But today, as Liem points out, “many of the best producers are seeking even narrower distinctions, making wines from individual parcels to produce even finer distinctions of terroir,” precisely what Nathalie and Sebastian are doing.

Côte de Sézanne

Côte de Sézanne is an historically important region some 20 miles southwest of Bergeres-les-Vertus. The Côte is dominated by chardonnay on chalk and marl, like its more famous neighbor to the north. In fact, the subsoil remains Cretaceous chalk throughout the Sézanne before turning to Kimmeridgian chalk as you move toward the Aube. As Liem points out, the more southerly location and heavier soils giver riper, more powerful and fragrantly fruity wines. Four of Nathalie’s 12 hectares here are in a parcel called “Chatet” near the village of Saudoy, and the soil here specifically is silex, a flint- and sand-based soil mixed with chalk, marl, clay and silica. The visually striking silex stones collect solar heat during the day, reradiating it to the vines at night.

What drew us to Nathalie Vignier in the first place was her range of single parcel Champagnes, which we had to wait two years to get. The names of the wines refer to the terroir, like the “Silexus Sezannensis Brut,” named for the silex of the Côte de Sézanne. Nathalie also has pure chalk parcels in Vindey (notably, near oak forests that the domaine is starting to harvest for barrels). Here the vines are planted selection massale from cuttings in Nathalie’s oldest parcels in Cramant. The 2008 Millésime Brut, made from this parcel, thus “reunifies mother and daughter” vines, as Nathalie sees it.

“A viticulture of reason”

Farming is done without pesticides or herbicides. “We practice a viticulture of reason, where common sense is the unit of measure,” Nathalie explains. “We’re practicing a more natural vine growing. We started to plow a couple of years ago, managing the natural growth of herbs and flowers. The aim is to enhance life and energy in the soils and to make the plants stronger, able to use their natural defenses. We try to find a balance and compromises between our imagination and the vineyard’s character and needs.” Sebastian adds, “We believe in sustainable agriculture and we are learning every day to get better, more respectful towards nature and consumers.”

The systematic search for exceptional parcels to vinify individually is also ongoing. “We continue to search for particular terroir expressions in the vineyard. In 2015, we started to work with two more single vineyard selections (one from Cramant and one from the Sézannais). But it will take a couple of years before those wines will leave the cellar,” notes Sebastian.

In the cellar

All J. Vignier bottlings come from grapes hand picked at optimum maturity, whole-cluster pressed, with separation of first and second press juices, using only the first press. There is cold settling for clarification and slow fermentation at low temperatures with various selected yeasts. All base wines are fermented in stainless steel tank and go through malo, with several months of tank aging. Bottling for the second fermentation occurs in spring. An extraordinary minimum of 48 months (up to 8 or 12 years for some cuvées) bottle aging before disgorgement is a house requirement. Dosage is “Extra Brut” (5 g/L) for all wines. Vintage wines are made only in stellar years.

Sebastian notes, “We’ve been hunting down sparkling wines for years. And we’ve found some really great wines in different places. But they didn’t taste like Champagne. So, there must be something special going on here. There is also something about the bottle ageing. The wines really get deeper and more complex after 36 to 48 months of aging. Not many sparkling wines age that long before leaving the cellar.”

The Vignier family motto is “La bonté de l’esprit et la grandeur de courage,” which means “the goodness in spirit, and the courage to greatness.” At the domaine, greatness comes from a singular focus on unique vineyard sites rendered patiently and with great care and understanding. The outcome of this practice and philosophy are wines of exceptional depth and pleasure, joyously ephemeral yet timeless.