“Our aim is to conserve every facet of what our vineyards produce. In our opinion, each wine documents its origin, its soil, the efforts of the winegrower, the weather, and the details of an entire year.” — Benedikt Baltes

If you’re looking for the wines of Benedikt Baltes, you’re in the right place. His work, his ideas, his singular focus on the extraordinary Spätburgunder (pinot noir) of Churfranken are as integral to the estate as ever. But in the decade since he took over the old vineyards and cellars of the City of Klingenberg, much has changed. Critically, the conversion to organic farming throughout the terraced, red sandstone vineyards, but also a focus on native yeast fermentations, local oak, an unrelenting quest to define Spätburgunder’s identity — and fatherhood. Benedikt and his partner (fellow Schatzi!) Julia Bertram now have a small son. Their life together is in the Ahr, where Benedikt grew up and where Julia’s family vineyards and future winery are. So, while Benedikt remains the guiding force at Steintal, more hands have come on deck. What hasn’t changed is the attention the estate rivets on Spätburgunder. The wines are singularly cool, slender, taut, and sculpted. This is because Benedikt thinks of them not in terms of other reds, even Burgundy, but of riesling. “Good pH, fine extraction, and reductive methods” are, he says, crucial to achieving the level of finesse and detail that mark out the wines. He’s convinced that Spätburgunder needs an “autonomous identity” and few in Germany are working as thoughtfully or brilliantly as he to resolve that definitively. The wines have an alluring strength, with delicate fruit and aromatics, grip and depth. All reward patience, or at least a good, long decant.

Winemaker

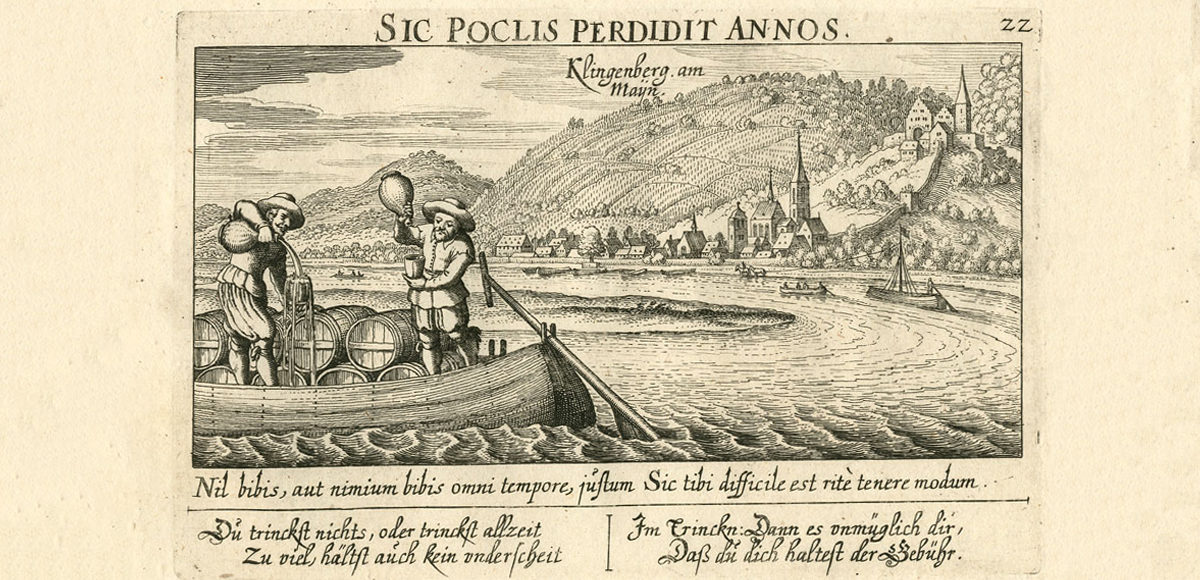

Benedikt was born and raised in the Ahr, where his family has long supplied grapes to the local co-op. He had other ambitions. After studying economics and enology, and interning in Austria, Hungary, and Portugal, Benedikt set out to find vineyards where he could make his own mark and push himself as a vigneron. It was impossible to find land in the Ahr so Benedikt scoured the country for a terroir in which he could drill down on Spätburgunder. He eventually found his way to the historic town of Klingenberg, in Franconia, with the opportunity to buy an ancient “urban winery” (founded in 1601—clearly ahead of its time!), with 10 hectares of old vines on steep, red sandstone terraces. “Life is short. You get maybe 40 vintages, so you need to go a region where the vines are of a certain age, where the previous generation understood where to plant. Old vines, good sites were important to me. I always thought I would start very small, with 2 or 3 hectares. But when I saw what the old Klingenberg winery had to offer me, I knew it was a dream come true.”

Starting fresh offered Benedikt the unique opportunity to enact his vision without being hamstrung by expectation or tradition. He also happened to have the great luck that climate change and improved understanding of Spätburgunder’s specific needs in the vineyard and cellar coincided with his arrival in this special place.

Benedikt brings a questioning spirit and tremendous energy to his pursuit of pinot perfection. “There is no preconceived notion he does not challenge,” notes Master of Wine Anne Krebiehl in her guide, Wines of Germany. “Ripeness? Trellising? Sustainability? He seems to relish challenges, and is actively experimenting, testing, pushing boundaries to see what will work.”

In keeping with this maverick outlook, Benedikt has learned “at least as much about Spätburgunder from Riesling estates as I have from top Pinot estates,” as he told Krebiehl. “Spätburgunder has such a different tannin structure from other red varieties and my winemaking aligns more and more with white wine: good pH, fine extraction, reductive methods. German Riesling is a fine wine with moderate alcohol, its long ripening period affords it enormous saltiness. It has an autonomous identity. Working out that identity is what is happening to Spätburgunder now.” He explains what fascinates him about the variety: “Riesling and Pinot Noir just offer more room for projection, more canvas to portray what happened in a vintage. I grew up in the Ahr with Pinot Noir, so I found my fun in that grape.”

In 2018, Benedikt was joined by Carl-Julius Cromme, who brings an international business background, including studies at Geisenheim, to Steintal. He interned under Benedikt, then returned to take on operations and marketing. He’s now stepped into the role of managing director, with the full intent of furthering Benedikt’s vision for Steintal.

History and Region

Weingut Stadt Klingenberg, founded in 1912, had been a thriving municipal winery with its own lauded vineyards. But by the time Benedikt took it over in 2010, revitalization was in order. He relished the chance. Churfranken, a small red wine oasis in northwestern Franconia, is still quite obscure, even among serious connoisseurs of German wine. The first written mention of viticulture in Klingenberg is from the 12th century. By the 17th, there was evidence of wines from the area being consumed in surrounding cities and exported as far as the Royal Court of Karl Gustav of Sweden. Today, Spätburgunder grows on steep, terraced slopes that soak up the sun — crucially, as Klingenberg sits at nearly 50 degrees north latitude. The brick-colored stone retains heat, insulating the pinot vines when nighttime temperatures plunge while its high iron content gives the wines a dusky minerality.

Vineyards and farming

Steintal now encompasses 12 hectares of terraced sites — all protected historic monuments —primarily on two slopes: Klingenberger Schlossberg (Große Lage / Grand Cru), with 25-60 year old vines, red sandstone in the steep terraces and tremendous diurnal temperature shifts that give the wines a unique combination of elegance, herbal notes, and a cool, minty minerality. Großheubacher Bischofsberg (Erste Lage / Premier Cru), with 20-40 year old vines, again on terraced red sandstone. Unlike the profoundly rocky and stony Schlossberg, this site has a sandier topsoil but the mother rock is still pure, red sandstone. The wines from the Bischofsberg are a bit more fruit-driven and charming in their youth. All sites are planted to French and German clones, propagated by massal selection. In Klingenberg and Großheubach the German “Ritter” clone predominates, while in Bürgstadt, the Dijon clone comes to the fore.

Benedikt started to cultivate the vineyards organically when he took over the winery in 2010, and gained full certification in 2018. He explains his thinking in terms of a trek: “When you go hiking, you are pursuing the joy of it. You don’t look for a way to make the hike shorter or faster. You look for a higher peak, something unusual, that challenges you. And so it is with wine, you don’t look for ways to spray something to make it grow faster or cheaper.” He’s also bothered by the idea of putting materials, e.g., copper, into his vineyards that don’t belong there. “It never goes away — it’s as if every day I left a coffee-to-go cup in my apartment.” He recognizes that this approach comes with costs. “I factor in that 10%-15% of my yield goes to nature — rot, birds. But if I leave all the inputs out of the equation, it works out.”

As Anne Krebiehl notes, even in Churfranken, Benedikt is “the rare Winzer without a tractor.” He insists on hand harvests and relies on Dwarf Breton sheep to manage foliage and aerate and fertilize soils. “In the Schlossberg, we were mowing everything by hand, and it’s almost 5 hectares of steep slope terraces. If you want your vines to live to 100, you can’t take the risk of damaging the vine trunk — fungus, esca, they can get in. Animals, for us, sheep, are the perfect solution.”

His keen interests in permaculture and holistic farming have propelled him toward the closed-system philosophy of biodynamics. The estate now cultivates stinging nettle from which to make anti-fungal teas. “For us, it’s more about making targeted use of the natural resources that we find in the vineyards as a sort of gift of nature,” notes Carl-Julius. “The greatest challenge to farming here is definitely farming on and maintaining the steep terraces. We do it all by hand, from estate wines to GGs. This requires time and intensive physical effort.”

In the cellar

“Our aim is not to ‘create’ wines,” says Benedikt, “but to conserve and preserve every facet of what our vineyards produce. In our opinion, each wine is unique, in which the vine documents its origin, its soil, the efforts of the winegrower, the weather, and the details of an entire year. Authenticity can only be achieved by recognizing the strengths of a special vineyard site and trying to capture them in the wine.” To this end, he relies on native yeasts and careful temperature control. The wines see 16 to 18 months in Halbstück, 300-, and 500-liter casks of wood from oak forests within 50 kilometers of the winery. There are zero chemical additions and the wines are bottled unfiltered. Carl-Julius emphasizes: “Our goal is to make wines that distinguish themselves through their freshness, transparency, precision, and depth of flavor. With age, these qualities become more and more apparent. Our wines need time to mature and fully unfold. However, should patience be a problem, we recommend opening our wines at least 4 hours before drinking and immediately decanting.”