“Precision requires human intervention at every stage. Between the earth and the vine, the soil preparation, the choice of varieties as well as their training according to the terroir. All those details, once gathered, make up my sense of balance.” — Yann Alexandre

Yann Alexandre is the eighth generation of his family to grow vines in the Petite Montagne de Reims, the third to make Champagne there. He and his wife, Séverine, share a passion for horticulture that directly informs their viticulture. “We grow the vineyard like a garden,” Yann explains. This is a high bar for two farmers working 6.3 hectares spread over 28 plots in nine villages. But is also essential to their philosophy: “I always try to put forward the characteristics of each plot of land and to reach perfect grape maturity and health.” Vitality is achieved through intensive hand work and regenerative practices to which the Alexandres have been dedicated since 1999. Swaths of bright yellow in the family vineyards signal the restorative impact of this approach: the region’s once ubiquitous tulipe de vigne was eradicated by intensive chemical farming; Yann and Séverine have nurtured the soils back to such health, the delicate flower has returned. As throughout the Petite Montagne, pinot meunier is the star, supported by pinot noir and chardonnay, the grapes matched to soils of calcareous clay, white marls, stones, and flint. Yann declares his aim is “as natural a Champagne as possible,” made from vital grapes, with minimal added sulfites, up to seven years lees aging, hand riddling and disgorgement, and “no detail left to chance.”

Courmas and environs

This 180-inhabitant village, 10 km (6 miles) southwest from Reims, takes its place within the Montagne de Reims, a sweep of low plateau, much of it forested, with vines covering its gentle slopes. Courmas belongs to the Petite Montagne, separated from the Grand Montagne by a main north-south road, the name a reference to the rather lower elevation of the vineyards here. The calcareous clay and stony-flinty soils tend to be shallow and well draining. In Courmas, Yann has 14 parcels, predominantly planted to meunier. These are matched by an equal number scattered to the north in Bouilly, in the 1er Cru villages Villedommange, Coulommes de Montagnes, and Vrigny, and in the sandier soils of Chenay and Merfy in the Massif de Saint Thierry and, to the south, in the stony, calcareous earth of Marfaux and, down in the Vitryat, St.-Lumier-en-Champagne. These sites have been selected for their advantageous “late climate,” as Yann calls it, and their soils, both of which serve to retain acidity and freshness in the wines.

Yann and Séverine Alexandre

Yann can trace his ancestry in the region back to 1690. Désiré Alexandre (Yann’s great-grandfather) vinified still wines and sold them to the big Champagne houses. In 1933, Marcel (Yann’s grandfather) and his brother, Gaston, decided to keep the still wines and in 1966, Yann’s father, Yves, started an eponymous label. Yann follows very much in this tradition, albeit with impressive education to back it up. After studying agronomics, viticulture, and oenology in Beaune, Rouffach, and Avize, and training in Rilly la Montagne, Champagne, in Lutry, Switzerland, and in Saint-Avit-de-Soulège, Bordeaux, he returned to his home village of Courmas. While at the Lycée de Beaune, Yann befriended students from Côte Rôtie, Chablis, Sancerre and he took pleasure in exchanging wines with them. In 1999, he returned to Courmas. Meanwhile, in 1995, he had met Séverine, who was then working in a different field. As Yann says, “I have been sharing my passion for wine with her ever since. We had two particularly successful harvests named Augustin and Tom in 2001 and 2002.” Today the family love cooking, eating, drinking wines, and listening to all types of music. “We love Mozart’s Requiem. We like being at home to take care of our garden. We like skiing with our two boys, now 17 and 18 years old. We like spending time with our friends and our parents. We like our job.” Yann has a long-held interest in growing and a love of plants, particularly roses and bonsais, and a passion for red wines “especially Burgundy” though, his wife points out, “he is open to others, when they are good.”

Vineyards and farming

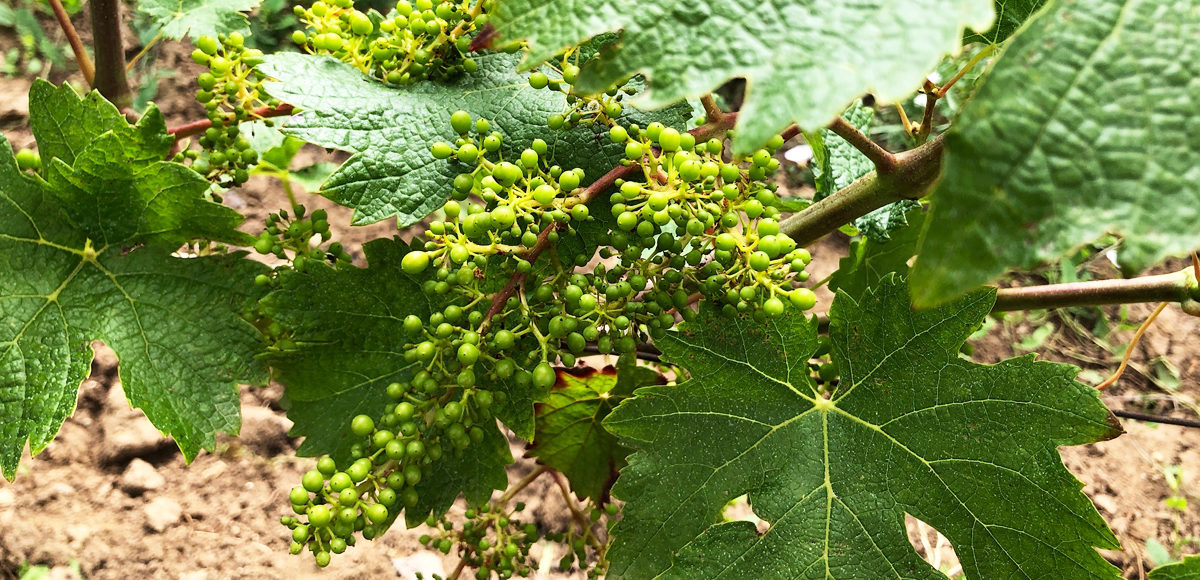

The Alexandre vineyards span 6.3 hectares of parcels with varying soil compositions all carefully matched to their varieties: 55% meunier, 30% chardonnay, 15% pinot noir. The primarily southwest-facing hillside sites encompass yellow tuffe, white marl, calcareous clay, white stone (“pierreux”) with flint. The vines, which are on average 25 years old, are a mix of clonal and massal selections. Yann’s farming is pioneering. His stated goal is “to make as natural a Champagne as possible” achieved through careful plant health strategy, respect for biodiversity, water resource management, cover crops, and plowing. In this way, he says, “the vine deepens its roots and becomes self-sufficient, erosion is stopped and the inputs are held back and made available for the next crop.” The reappearance of the tulipe de vigne, a delicate flower once present everywhere in the region but wiped out by chemical farming, is an encouraging confirmation of Yann’s approach, echoed by a Level Three High-Value Environmental Certification from the French Ministry of Agriculture earned since 2015. “The thorough maintenance of the soil allows for the self-development of the vine, which takes everything it needs,” Yann notes. Vine training, green pruning and shearing of lateral shoots to thin the vine and ensure the ripening of the grapes are all done by hand. Likewise, sequential, selective harvesting of the various plots to ensure perfect grape ripeness.

In the cellar

Each variety and each plot is vinified separately “to ensure the blending is balanced and fresh,” says Yann. Yann selects the most propitious yeasts, adds minimal sulfites (under 50mg/l), relies on temperature-controlled fermentations in stainless steel and oak (“it depends on the plots — for stainless elevage until bottling, seven months, for oak, three months in barrel and then another three to four in stainless until bottling”). Decisions on malo “depend on the wines” though Yann notes he is “doing less” so as to preserve acidity and freshness. Wines remain on the lees in the Alexandres’ cold cellar: five years for the Brut Noir, seven for the Grand Reserve 1er Cru. The wines are a mix of vintage and nonvintage, with the exceptional Sous-les-Roses Blanc de Noirs representing a “late year but great summer giving beautiful matured grapes” from a single parcel in Courmas and the Blanc de Blanc depicting the “early but very well balanced” 2011 vintage. Hand riddling, disgorgement, and three months’ rest post dosage are the rule. “My wines reflect the history of the region and my sense of balance. They also reflect a particular wish at a particular time. No detail is left to chance. I need to be certain that each wine I make will bring pleasure to the one who tastes it and stimulate the desire to share,” Yann summarizes.

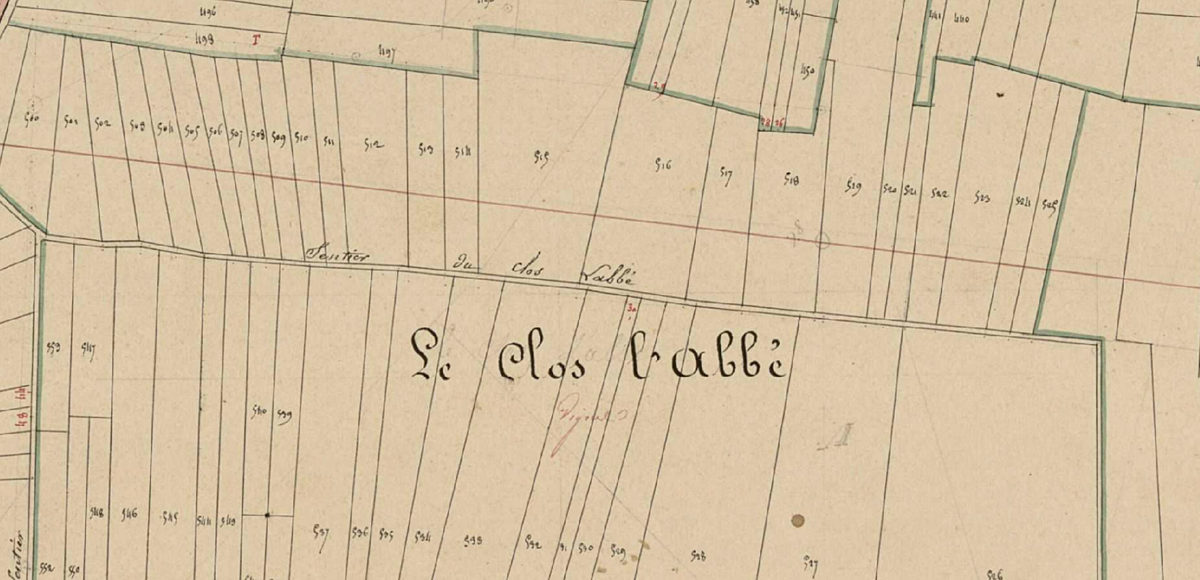

Hubert Soreau is not from Champagne and like many outsiders who have found their way into traditional, European viticultural regions (ref. Tony Bodenstein at Prager, Michi Moosbrugger at Schloss Gobelsburg, Ted Lemon at Dujac), he is making waves. He is part of the single vintage, single parcel, single barrel approach currently utilized by a handful of growers in the region, but he also brings to his work a perspective unencumbered by traditions and conventions. Le Clos l’Abbé is a single parcel outside of Epernay where the Vallée de la Marne and the Côte des Blancs meet. This parcel was originally planted in the 9th Century after the Bishop of Reims ordered it cleared for viticulture. At that time, it was known as Mons Ebbonis and afterward, as Mont de Bon in the 14-17th Centuries when the parcel was predominately planted to red grapes. The Counts of Epernay then purchased the parcel in the 17th Century from the Bishop of Reims, had to build an Abbey on the site in addition to paying remunerations, and it has been used for Champagne production ever since.

Hubert was born in the far north of France, in the town of Maubeuge, on the border of Belgium. His family moved to Champagne, in a house across from Le Clos l’Abbé, where the site essentially served as his back yard. His parents were able to purchase a small parcel in 1993 and Hubert added to that original holding with another purchase in 2003. He never uses pesticides or herbicides and he picks late in the season with an average ripeness of 11° Baumé. Fermentation takes place in both used barriques and neutral 300L Hautvillers oak barrels and is finished with minimal dosage.

The Pouillon family has been growing grapes in the region for over a century, but it wasn’t until 1947 when Fabrice’s grandfather, Roger Pouillon, decided to produce wine from his holdings along with the help of his wife, Bernedette, and his uncle, Louis Baulant, a well-known winemaker and consultant in the region. The estate continued to grow over succeeding decades as grape contracts expired allowing the family terroirs to be reincorporated into the Pouillon estate. James Pouillon, Fabrice’s father, joined the firm in 1964 and modernized the cellar by adding enamel-lined tanks and gyropalletes. Fabrice joined his father in 1998 after finishing degrees in both business and oenology school, and he has taken the winery in an exciting new direction. Working in the grand cru of Aÿ and throughout the Vallée de la Marne and the Montagne de Reims, Fabrice is crafting articulate, expressive, terroir-driven wines that are vibrantly aromatic and intricate on the palate.

Fabrice Pouillon is dedicated to the vitality, energy and health of his vineyards. In 2003, he began the work of conversion to organic viticulture and today he incorporates biodynamic principles into his work including compost management, spraying herbal “teas” and applying 500 and 501 treatments. He currently uses only organic compounds for fertilizer, pheromone confusion to ward off pests, cover crops to restore nutrients in the soil and plows alternating rows to keep vine competition and soil aeration consistent despite varied growing conditions. He is also a member of Lutte Raisonnée.

Fruit is harvested by hand and transferred to an ancient wooden pneumatic press. The juice then falls via gravity into enameled iron fermentation tanks. The wines are aged in a combination of stainless steel and older oak demi-muids and barriques where everything undergoes full malolactic fermention. Reserve wines are aged for up to 18 months in 700 liter, old-oak barrels. There is also a stainless-steel “solera” with wines dating back to the late 90’s. The results are electric, terroir driven wines with high-toned aromatics, fresh acidity, and incredible length. These are wines that are light on their feet yet possess depth and intensity that continually unfold with each sip.

The Pouillon family’s holdings are in Aÿ, Mareuil-sur-Aÿ and Avenay Val d’Or in the Grande Vallée, Epernay and Festigny along the Marne River, and Tauxières-Mutry, just to the north in the Montagne de Reims. The majority of the plantings are to pinot noir (3ha), followed by chardonnay (2ha) and pinot meunier (1ha).

The most exciting recent changes at Champagne Pouillon are the introduction of single parcel cuvées, including the upcoming release of the tête de cuvée, 2008 Chemin du Bois.

With holdings of old vines in some of the greatest terroirs in the Côte des Blancs, Pascal Doquet has emerged over the last decade as one of the premier vignerons in Champagne. After he took over his family estate, Doquet-Jeanmaire, in 1995 when his father retired, Pascal established his eponymous Domaine in 2004. Today he farms just under 9 hectares of vines including prime parcels in Vertus, Le Mont Aimé and Le Mesnil-sur-Oger—including his illustrious old vines in the parcel “Champ d’Aoulettes.” Natural farming and dedication to vineyard health is the driving force for Pascal; in fact, he rarely discusses fermentation—his passion is in the vineyards. The Domaine has been certified Organic since 2010.

Pascal started with his parents in 1982 and his first vintage was 1995 when he was one of the first members of “lutte raisonnée.” He pushed his environmental concerns with his parents further and stopped all chemical treatments in 2000. Ultimately, the company split in 2004 with his sister taking some parcels and Pascal and Laure taking the rest. One can easily see the difference between the farming influence of Pascal and Laure with a tour of the vineyards compared to the parcels they no longer manage.

Pascal employs extensive cover crops and does his work with a special, ultra-light tractor as to avoid any unnecessary compacting of the soil. Plant-based treatments are employed as Pascal seeks to reduce his use of copper and sulfur as much as possible. He is exceptionally focused on vineyard management in order to express the subtleties of his terroir and to make honest wines. As Pascal often says “It’s the viticulture that makes the difference, not the vinification.”

In this spirit, the harvest is done by hand with strict triage taking place in both the vineyards and the cellar. The grapes are pressed pneumatically and only the best parts of the cuvée are used. The must is fermented with indigenous yeast, most often in enamel-lined tanks, but neutral oak is used in parts of the vintage Coeur de terroir cuvées. The vin-clair is left on the gross lees for a minimum of five months and receives minimum bâtonage. Almost all of the wines undergo malolactic fermentation and all cuvées are aged for a minimum of three years before disgorgement and release.

The wines of Pascal Doquet burst with energy and verve and deliver mineral-laden, multi-layered expressions of his terroirs. These are wines for people looking to experience the scintillating flavors of the Côte-des-Blancs “sans maquillage.”

“Less is more.

Stay close to your vines.

Never think you know it all.

Nature decides.” — Nathalie Vignier and Sebastian Nickel

A domaine of “hidden treasures”

The Vignier family history in Champagne dates to 1530, the time of Nicolas Vignier of Bars sur Seine. Nicolas was a physician, lawyer, theologian, and court historian for Henry III. His descendant, Nathalie Vignier, is now the tenth generation to pursue viticulture and winemaking in Champagne, and the sixth generation to do so in the grand cru village of Cramant, in the Côte des Blancs.

In the early 20th century, Nathalie’s grandfather, Paul LeBrun, had two hectares, taken over from his father, Henri LeBrun. Paul resolved to become an independent vigneron by separating himself from the big négociants after World War I and was among the first to do so in the Côte des Blancs. He established Champagne Paul LeBrun in the 1930s. Frank Schoonmaker — a long-time collaborator with Alexis Lichene in the wine trade, and together two of the most influential figures in shaping American views on European wine in the last century — was the first to import the wines to the U.S.

Nathalie and her brother, Jean, took over the domaine from their parents 12 years ago, with Jean on the business side and Nathalie in the vineyards and cellar. Nathalie’s husband Hubert Soreau (another Schatzi!) is the winemaker at Le Clos l’Abbé in Epernay. Through him, Nathalie and close family friend Sebastian Nickel (whose grandmother’s family farmed land around Sézanne and held plots that became AOC Champagne in the 1960s) made the connections that enabled them to realize a shared vision and dream — one with roots in Nathalie’s father’s profound understanding of the land. He had always told them there were “hidden treasures” in the 16.5 hectares of chardonnay in Côte des Blancs and Côte de Sézanne that constitute the Vignier LeBrun vineyards.

The epiphany

In 2006, Nathalie and Sebastian began their hunt for those treasures, sampling berries before harvest, tasting wines after fermentation, working through small batches of old wines in the cellar. They realized Nathalie’s father was right. That epiphany compelled them to try making a small range of wines from a narrow selection of plots around Cramant, Chouilly, and Oiry, as well as in the Sézannais — all, Sebastian says, “showing a strong personality.”

“The first fruits for the future of J. Vignier were picked in 2007 and 2008 (a fantastic vintage!),” Sebastian explains. “At that time, we did not know that it would lead us to a totally new approach to winemaking and viticulture. We just picked and fermented some selected vineyards separately to see what it would look like.” Since then, Nathalie and Sebastian have been gradually aligning the domaine to their shared philosophy: farming without herbicides or pesticides, focusing on small production, single parcel wines of higher ripeness and extraordinarily long lees aging (up to 12 years), and a foreseeable return of oak to the cellar.

A shared vision

Nathalie says she realized as a child that she wanted to be a winemaker, but the impetus was not wine itself. “I was impressed to hear people talking a foreign language at my grandparent’s place, so I wanted to work abroad. After my studies, I found a training period in Germany and England. During holidays, I came back to help my parents in the winery and vineyards. Finally, I said to myself: This is what I really want to do! Not paperwork, but growing vines, making wine, and selling what we have made. In 1994, my father asked me to come back.” Nathalie did go to business school and worked for a time as the chief agricultural expert for insurance companies, specializing in hail and frost damage to vines. This put her in touch with a range of growers in both Champagne and Burgundy.

Sebastian brings an outside perspective. He’s German and grew up in the Netherlands and Germany. He studied biology, and, crucially, spent a year at the INRA (the French equivalent of the USDA) in Dijon, where his lab was so close to Gevrey-Chambertin, he fell under its spell. Soon he changed course to study winemaking and enology, then went on to work in vineyards and cellars in the Languedoc, Minervois, and Australia.

Nathalie and Sebastian now collaborate closely on the J. Vignier wines. All decisions about blending, dosage, and vineyard selections are shared. Sebastian says he and Nathalie are guided by a deep respect for both the long tradition and the future potential of the domaine, as well as the work and wines of Mignon, Agrapart, Laherte, Dehours, Jacquesson, among others. “But wines and growers from other regions also inspire us. We all love the northern Rhône, Burgundy, Barolo, Gigondas, Malbec from Cahors, and German riesling, of course!”

Wines of two côtes

Many of the small grower-producers who work within Champagne are in the Côte des Blancs, where the big houses traditionally have owned fewer vineyards. Planted between 1950 and 2010, the Vignier vineyards are deeply rooted in the chalky slopes of the grand cru villages of Cramant, Oiry and Chouilly. Nathalie’s family also own parcels in the warmer Côte de Sézanne, about 50 km to south, where Nathalie’s family has been acquiring plots for several decades.

Côte des Blancs

Cramant and Avize constitute what Peter Liem calls “the historical heart of the Côte de Blancs,” noting that these were the first villages of the area to be classified grand cru. The chalky clay soils of Cramant give a richness and power that past winemakers blended with the comparatively spare wines of Le Mesnil-sur-Oger for balance. But today, as Liem points out, “many of the best producers are seeking even narrower distinctions, making wines from individual parcels to produce even finer distinctions of terroir,” precisely what Nathalie and Sebastian are doing.

Côte de Sézanne

Côte de Sézanne is an historically important region some 20 miles southwest of Bergeres-les-Vertus. The Côte is dominated by chardonnay on chalk and marl, like its more famous neighbor to the north. In fact, the subsoil remains Cretaceous chalk throughout the Sézanne before turning to Kimmeridgian chalk as you move toward the Aube. As Liem points out, the more southerly location and heavier soils giver riper, more powerful and fragrantly fruity wines. Four of Nathalie’s 12 hectares here are in a parcel called “Chatet” near the village of Saudoy, and the soil here specifically is silex, a flint- and sand-based soil mixed with chalk, marl, clay and silica. The visually striking silex stones collect solar heat during the day, reradiating it to the vines at night.

What drew us to Nathalie Vignier in the first place was her range of single parcel Champagnes, which we had to wait two years to get. The names of the wines refer to the terroir, like the “Silexus Sezannensis Brut,” named for the silex of the Côte de Sézanne. Nathalie also has pure chalk parcels in Vindey (notably, near oak forests that the domaine is starting to harvest for barrels). Here the vines are planted selection massale from cuttings in Nathalie’s oldest parcels in Cramant. The 2008 Millésime Brut, made from this parcel, thus “reunifies mother and daughter” vines, as Nathalie sees it.

“A viticulture of reason”

Farming is done without pesticides or herbicides. “We practice a viticulture of reason, where common sense is the unit of measure,” Nathalie explains. “We’re practicing a more natural vine growing. We started to plow a couple of years ago, managing the natural growth of herbs and flowers. The aim is to enhance life and energy in the soils and to make the plants stronger, able to use their natural defenses. We try to find a balance and compromises between our imagination and the vineyard’s character and needs.” Sebastian adds, “We believe in sustainable agriculture and we are learning every day to get better, more respectful towards nature and consumers.”

The systematic search for exceptional parcels to vinify individually is also ongoing. “We continue to search for particular terroir expressions in the vineyard. In 2015, we started to work with two more single vineyard selections (one from Cramant and one from the Sézannais). But it will take a couple of years before those wines will leave the cellar,” notes Sebastian.

In the cellar

All J. Vignier bottlings come from grapes hand picked at optimum maturity, whole-cluster pressed, with separation of first and second press juices, using only the first press. There is cold settling for clarification and slow fermentation at low temperatures with various selected yeasts. All base wines are fermented in stainless steel tank and go through malo, with several months of tank aging. Bottling for the second fermentation occurs in spring. An extraordinary minimum of 48 months (up to 8 or 12 years for some cuvées) bottle aging before disgorgement is a house requirement. Dosage is “Extra Brut” (5 g/L) for all wines. Vintage wines are made only in stellar years.

Sebastian notes, “We’ve been hunting down sparkling wines for years. And we’ve found some really great wines in different places. But they didn’t taste like Champagne. So, there must be something special going on here. There is also something about the bottle ageing. The wines really get deeper and more complex after 36 to 48 months of aging. Not many sparkling wines age that long before leaving the cellar.”

The Vignier family motto is “La bonté de l’esprit et la grandeur de courage,” which means “the goodness in spirit, and the courage to greatness.” At the domaine, greatness comes from a singular focus on unique vineyard sites rendered patiently and with great care and understanding. The outcome of this practice and philosophy are wines of exceptional depth and pleasure, joyously ephemeral yet timeless.

“Today, I am in the same state of mind as the one that has always animated me. That is to say, placing respect for humans but also for natural resources at the heart of my activity.” —Xavière Hardy

Xavière Hardy (Les Terres Bleues) is the only wine grower in her village of La Chapelle-Glain. It puts her well outside the nearest Loire AOC of Côteaux d’Ancenis in every sense.

After discovering that natural wines were those that challenged and captivated her, she gave up a long career specialized in environmental engineering and plunged into the unknown: In 2013, she began planting 1.5 hectares of uncharted ground, tethered only to the idea of farming pinot gris, pinot noir, and grolleau noir biodynamically and making sulfur-free natural wines that express her connection to the land and the environment. The results are defined by freshness and energy, drawing a direct line to the blue schist and cool oceanic clime of her chosen terroir.

In her deliberate explorations of this uncharted terroir and through her unfettered approach in the cellar, Xavière has uncovered an entirely new character for these varieties.

Region

Xavière was drawn to a specific piece of land, not a region or an ideal. So it is this one place that is relevant: a small plot that had been managed organically for more than 20 years. The location was no accident. “In a context of global warming, vines and winegrowers must adapt,” she reasons. “Planting farther north was of interest in response to these changes, so the wines keep their characteristics.”

But planting vines in La Chapelle-Glain was officially forbidden. With the help of Jacques Carroget of Domaine de la Paonnerie, something of an ambassador for natural wines in the region, Xavière put pressure on local institutions. They ended up giving in. For her, a true terroir study was “an essential prerequisite to ensure the relevance of this project and to choose grape varieties perfectly suited to the local context,” she says, with the analytical precision of her previous profession.

Winemaker

“I had always been interested in vines and wine, but it was when I discovered ‘natural’ wines that I really challenged and captivated,” Xavière says. “‘Natural’ wines have generated, for me, the most beautiful emotions during tastings.” So much so, that in 2017, she left a long career in environmental engineering and gave herself over entirely to their creation and care. “I started from zero. No vines, no cellar, no equipment, no stock,” she points out. She sought the advice of organic and biodynamic winegrowers including Carroget and Guy Bossard of Domaine de l’Ecu. Then she struck out on her own.

“I have a very strong link to the environment, to water, the earth, nature, so it was something that attracted me. I would never have thought of doing that in La Chapelle-Glain. But I had a soil study carried out by the viticultural soil unit and I realized that I had a plot on which it was quite possible to plant vines!,” she explains.

The land itself and the context in which she lives – near her son and daughter, who raise rare Solognote lambs and Longuet pigs for meat, Lacaune sheep for cheese, and work with heritage grains for sourdough breads – “in complete autonomy” dictated the parameters of her micro-estate. In working to honor her family’s products by making wines from the same terroir and values, she is closing a startlingly virtuous circle.

Vineyards and Farming

Les Terres Bleues’ sky-blue Anjou schist is mirrored in the azure-colored stone that makes up a wall of Xavière’s house. Such terroir has a magnetism of its own. But it is not a soil type for just any grape variety.

Every vine at the estate was a deliberate choice, in precise alignment with the schist and climate. No holdovers or accidents here. “I created my estate to be able to initiate vine management on new ‘land’ free from any chemical intervention,” she notes. This raises the beautiful question of what is possible when a grower starts from a clean slate, motivated by land and love but informed by scientific understanding and profound appreciation for the interactions of human, crop, and climate.

Her half-hectares each of massal selected pinot gris, pinot noir, and grolleau noir on carefully selected rootstock are trained quite uncommonly on chestnut stakes in a style Xavière feels respects the original trellising environment of vines: trees.

It almost goes without saying that Xavière sought and gained ECOCERT organic certification from the outset, gaining DEMETER biodynamic certification in 2019. She follows the lunar calendar, works with preps and herbal teas of nettles, comfrey, horsetail, oak bark, willow, and other plants to minimize reliance on copper. “The objective,” she notes, “is to allow the vine to strengthen its own resistance to disease and to improve exchanges between soil microorganisms and its root system.” The ecosystem is as important as the vine itself, in her view. She actively preserves the hedges that surround her plot, creating a multi-species refuge, allowing water to seep into the soil and limiting the risks and effects of drought, protecting the soil from erosion, and generating humus.

Apart from harvest and vine tying, Xavière does everything herself. She works the soils in the spring, but otherwise leaves a cover crop of what she calls “weeds” that grow spontaneously in the vineyard. Her belief is that “if these weeds are present, it is because the soil needs precisely these species. I could never establish a more relevant and adapted vegetation cover.” She does not manage the canopy, allowing it to develop in accord with the grapes’ need for sun protection.

In the Cellar

Working on a very small scale and “without any oenological input,” Xavière’s objective is to create wines that are direct expressions of the land and her own determined character. Spontaneous fermentation in open-topped vats is followed by aging in mixed-age used barrels and vats. The wines are unfined, unfiltered, and receive zero sulfur additions. Bottling is typically done in the spring after harvest. Of critical importance to Xavière is that she has free reign to adapt her vinifications to the characteristics of each vintage.

“Today, I am in the same state of mind as the one that has always animated me,” Xavière reflects. “That is to say, placing respect for humans but also for natural resources at the heart of my activity.”

“Muscadet is and will remain our iconic wine.” — Cyrille and Sylvain Paquereau

Muscadet. The bracing, salt-stung essence of the North Atlantic in a glass. A classic and still affordable pleasure. But also, in recent decades, a wine of diluted identity. Alexis Lichine, in his masterly Wines of France, saw fit to accord Muscadet a scant paragraph. Fortunately, a new wave of producers in the Pays Nantais is reviving a true understanding of both their variety, melon de bourgogne, and the precise set of soils in which it thrives. Cyrille and Sylvain Paquereau of Domaine de l’Epinay are of this movement. They represent the fifth generation of their family to work a 16th-century estate in the heart of Clisson, now an established Muscadet cru. Conversion to organics and concentration on the precise match of grape to terroir distinguish their tenure. Though we may think of Muscadet as a wine of acid-driven freshness, this is not inherent in melon, but rather a quality only brought out by high pH soils—notably, gabbro and the gravelly granite of this southernmost part of the Sevre et Maine appellation. The range at Domaine de l’Epinay focuses on melon’s terroir transparency, aided by spontaneous fermentations, minimal added sulphites, and up to 36 months lees aging in underground cement tanks. Cyrille and Sylvain’s wines urge us to look at Muscadet in the light of terroir and tradition, underscoring the wine’s capacity both for refreshing directness and more powerful, age-worthy expressions.

History

In the 16th century, Domaine de l’Epinay belonged to the Espinozas, a wealthy Spanish trading family. After the French Revolution, a local civil conflict known as the Vendée Wars resulted in the burning and destruction of many buildings and archives in and around Nantes, leaving few records. “But, we know that the culture of the vine already existed,” note Cyrille and Sylvain. “It started at the end of the 17th century, thanks to monks from Burgundy. They brought with them their grapes—especially the melon de bourgogne.” The Pays Nantais had, in fact, been a red wine region until the lethal winter of 1709. Replanting was to prolific white varieties; high-yielding melon de bourgogne, in particular, satisfied Dutch traders’ appetites for neutral base wines for their brandies. The grape flourished in the cool, damp climate and granitic soils around these parts while the presence of small, navigable rivers, all connected to the Loire and the Atlantic, facilitated the wine’s transport and trade.

Fast forward to 1900, the year the Paquereau family took over the domaine. For much of the 20th century, they managed it as a typical mixed farm of dairy, cereals, and vines. In the early 1970s, Albert and Odile Paquereau narrowed their focus to wine while expanding their holdings from 5 to 30 hectares. In 2000, Cyrille, their elder son, returned to the estate from a range of apprenticeships and trainings, and in 2006, younger son Sylvain followed, at which point the brothers took over from their parents. In 2011, Cyrille and Sylvain began the conversion to organic farming, starting with the Clisson cru holdings. Today, the domaine stretches to 52 hectares, nearly half of which are devoted to melon.

Region

Domaine de l’Epinay is a scant 40 miles inland from the sea and the quintessential maritime climate is decisive for melon de bourgogne. It is well adapted to the combination of cool, steady sea breezes and just-adequate sun. Critically, the grapes ripen fully by early September, before the arrival of the rain-bearing equinox tides.

Melon is a natural crossing of pinot blanc and gouais blanc, making it kin to both gamay, which shares melon’s famous predilection for granite, and chardonnay. David Schildknecht has pointed out that its “discreet charms easily morph into vapidity and thinness at high yields” and that “like a white tablecloth, it registers even tiny phenolic imperfections.” Therefore, scrupulous farming and strictly controlled yields are essential to coaxing melon into greater expressiveness.

Geologically, the brothers explain, “we are on the Armorican massif, an old, eroded mountain full of geological faults. This mosaic of granite, schist, mica schist, and gabbro [an intrusive igneous rock chemically similar to basalt] can make one think of Burgundian vineyards by its great diversity.” Soils are shallow, sandy, and poor but retain heat well and fracture easily to allow deep root penetration. They also tend to be basic, which elevates acidity in the grapes.

The introduction of a cru communaux (communal cru) system for Muscadet was an important step in defining terroirs and imposing new standards for yields and sur lie elevage. Clisson was among the first three cru to be classified in 2011, in recognition of its exceptional well-drained, granitic soils and the potential wines grown here have to age into power and richness.

The winemakers

“Since we were very young, we participated in the work of the family farm,” say Cyrille and Sylvain. Cyrille studied viticulture and enological technology at the local winemaking school, then added further studies, notably at Pessac Léognan (Château Pape Clement) and on San Juan Island, in Washington. Sylvain pursued degrees in science and agricultural engineering, specializing in viticulture and oenology, at schools in Angers, Toulouse, Montpelliers, and Geisenheim, Germany. To balance this with practical experience, he worked for a wine merchant in the Loire Valley for several years. Today, the domaine consists of Cyrille, Sylvain and his wife, Anne Gaëlle, their children, and a small crew. “We chose an exciting job, always surprising and rich with beautiful encounters. Wine is a link between people who like to chat and discover each other. It is in this spirit that we like to work and that we flourish,” the brothers note. They find surprising satisfaction in meeting the tests of farming in an era of climate change. “It is a reality that we winemakers notice every day. We must adapt and produce our wines in the best possible environment and try to keep the character of our wines. A real challenge for us: exciting and motivating!”

Vineyards and farming

“Muscadet is and will remain our iconic wine,” Cyrille and Sylvain assert. “We are very attached to it. We like to work its different expressions on our soils that have a lot of identity. The crucial point is harvesting at the optimal moment, adapted to varietal and terroir. Since the end of the ‘90s, we have changed many things. Our first year of organic conversion was 2011, with Muscadet. Since then, we have gradually expanded and 2018 was our first vintage grown entirely organically.”

The main idea for Muscadet at the domaine is old vines, low yields, hand harvests. The Sélection bottling comes from 25- to 30-year-old vines grown on sandy-silty soils over gabbro. Cyrille and Sylvain point out that “the cycle of melon de bourgogne on these lands is rather ‘Tardif’ and these parcels are often picked towards the end of the harvest.”

Esprit is grown on plots of similar age on more granitic bedrock, with gravel-silt topsoils. But, the brothers note, melon comes to ripeness much earlier here, so these plots are often picked from the first week of harvest.

Clisson, Epinay’s great vin de garde, hails from 2.5 hectares within the eponymous cru. Soils are gravel and silt over “granite de Clisson” bedrock. It is a warm, early-ripening site with vines planted more than a half-century ago. Harvests are pushed to optimal maturity, typically at least three weeks later than Sélection (“to be at the limit, just before the stage of overmaturity,” the brothers say) and yields are tightly delimited at 40 hl/ha to maximize terroir expression.

There is also a set of traditional method sparkling wines from chardonnay, pinot noir, cab franc and other varieties, all estate fruit, that bring a charming ease.

In the cellar

“Our cellar work is classic,” say Cyrille and Sylvain, meaning temperature-controlled spontaneous fermentations and sur lie aging in buried tanks. Lees aging is, of course, synonymous with Muscadet. Cyrille and Sylvain explain its importance: “Melon de bourgogne is an aromatically discrete variety, which expresses its differences only after aging on lees.” Yeast autolysis, they note, “protects the wine from oxidation and gives it a freshness and a characteristic beading, thanks to a significant presence of carbon dioxide.”

“In our region,” they continue, “the wine is stored underground in concrete tanks, the interior walls covered with glass or grès [a type of ceramic stoneware]. The tanks are a depth of 2 meters, the volume between 30 hl and 120 hl. They are accessed from the top through a hatch, through which we proceed to batonnage. We move the lees, which fall naturally by gravity to the bottom of the tank and are regularly resuspended in the wine, avoiding oxidation of the wines and preserving their aromatic freshness.”

The Sélection wines are bottled in the spring following harvest, preserving their vibrance and the characteristics of the gabbro terroir. Esprit stays on its lees for nine months without any racking.

For Clisson, Cyrille and Sylvain explain, “the juice is put directly in vats for a fermentation of two to three weeks. The wine is then racked and stays on its fine lees for nearly 36 months. It can ripen slowly and enrich itself on its deposit until it is bottled.” It is a powerful wine of character, with an intense and complex nose of acacia and quince, revealing the rich texture and fine balance of a great terroir of Muscadet on a relatively light alcoholic frame.

The traditional method sparkling wines are from base wines blended early in the winter following harvest and can vary slightly each year. The Blanc is typically a blend of 50% chardonnay, 35% folle blanche, and 15% pinot noir. The Rose is a blend of 60% pinot noir, 25% abouriou, and 15% cabernet franc.

“The right gesture at the right time in permanent awareness of respect for nature.” — Xavier Cailleau

Château de Bois-Brinçon

In the heart of Anjou stands Château de Bois-Brinçon, a domaine founded in 1219 by the Saint Jean d’Angers hospital. The domaine remained church property until 1791, when it was confiscated by the state and sold as a national asset. Xavier Cailleau is now the fifth generation of his family to own and work some of the oldest plantings of chenin, grolleau, and cab franc — 125 years and older — in the Loire. Xavier and his wife Géraldine, along with a small team, farm their 24 hectares biodynamically, out of profound conviction and in perpetuation of tradition, to offer “the true face of the soil.”

Reconnecting with tradition

Despite this venerable history, the domaine went through a difficult period in the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ’80s, when winemaking ceased and grapes were sold off. It was during this time that Xavier, then a boy, took a harvest visit to a vigneron uncle and began to wonder why wine was no longer made at Bois-Brinçon. He found harvest to be a time filled “with lots of happy and festive memories,” he recalls. More than this, “at the age of 12, I understood that we have a unique place with an exceptional history.”

Xavier Cailleau

Xavier went on to study first arboriculture, like his father Jean, then viticulture and oenology, at Libourne. His education included practical training in Saint Émilion with Pascal Delbeck at Château Belair and in Alsace with Jean-Michel Deiss at Marcel Deiss. Equipped with this knowledge and experience, Xavier set out to revive winemaking at Bois-Brinçon in 1991. “At the beginning, it was a real challenge to return to winemaking and the desire to make wines with a terroir identity,” Xavier acknowledges. A steady evolution, first to organics, then biodynamics, ensued. Xavier noted how quickly the vines responded to this approach, as the grapes began to offer “the true face of the soil.”

“Vinification by terroir”

“The Anjou region is a mosaic of very varied and rich terroirs,” Xavier explains. “Being at the junction of the Armorican Massif and the Paris Basin, the Bois-Brinçon vineyards offer a rare diversity of soils and landscapes spread over six communes and eight different terroirs.” The domaine’s key soils include several types that are quite specific to this part of the Loire: volcanic rhyolite and spilite; marne à ostracées, primarily composed of fossilized oyster shells interspersed with clay and limestone; and grès, consisting of fossilized coral and sponge-like rock atop pure Anjou tuffeau. Xavier is convinced that “vinification by terroir” is essential to the transcription of soil to wine.

Beyond the diversity of soils, Xavier believes a key advantage of Bois-Brinçon’s location is its climate, moderated by the Loire. What makes it unique is “the historical presence” of chenin, pineau d’aunis, grolleau, and cabernet franc. He is acutely aware of the value of his densely planted old-vine parcels, which average 50 years for his single-vineyard bottlings, with some vines as old as 125 years. Yields are also remarkably low. Bois-Brinçon’s 0.8 hectare of the famed Montbenault vineyard is harvested at just 20 hectoliters per hectare. Everything is in service to his ideal: “to transcribe the notion of landscapes that we discover plot by plot in the wines.”

Xavier and Géraldine’s philosophy of farming biodynamically “requires having the right gesture at the right time in permanent awareness of respect for nature.” They continually evaluate new and alternative practices to this end. Their commitment extends to a regional initiative to plant hedges and develop natural areas so birds and beneficial insects can restore the balance of nature in and around the vineyards.

In the cellar

“We accompany the wines without useless and traumatic interventions,” Xavier says, “like a parent who sees his children grow up and accompanies them so they take the right path.” In the cellar, his focus is on a long, slow, gentle “infusion” style, with an eye to elegance and freshness. The reds are all de-stemmed, do not undergo pigeage, are fermented in cement tank, and raised in neutral wood and stainless steel. The whites are strictly selected in the vineyard to remove botrytis (healthy, botrytized grapes are only chosen for the Coteaux du Layon), and whole clusters are given long, slow, gentle press cycles, with fermentation in neutral wood. Crémant is sourced from a tiny parcel of pure tuffeau topped with grès, tuned specifically for this wine. Primary fermentation occurs in temperature-controlled stainless steel tanks. The crémant is bottled with a percentage of natural grape sugar left in and secondary fermentation takes place in bottle, followed by two years of elevage sur latte.

“An ambition: respect for the vines, the soil and people.” — Jean-François Regnier

The Regnier-David estate

The Régnier family has been established in Meigné-sous-Doué since at least the Revolution. I found a certain Urbain Rainier (the current spelling dates from 1820) in the municipal archives! underlines Maurice Régnier, who created the family winery more than 60 years ago on an agricultural structure that was already producing wine. Very concerned about respecting the soil and the environment, Maurice Régnier and his wife Monique David wanted to direct their estate from 1973 towards less treatment, more attention to the natural cycle of the vine: a pioneering approach which may seem original to neighborhood at the time! The conversion to organic was launched in 1994 and the bottles could finally bear the label of the label in 1997. Today, Jean-François, their son, works in non-certified biodynamics and maintains this concern for a deep understanding of the vine and the terroir inspired by his ancestors.

Jean-François Regnier

Jean-François developed a passion for working the vines from childhood and accompanied his parents as soon as he could in the rows and on the machines. After a viticulture/oenology BTS at the Lycée Edgard Pisani in Montreuil-Bellay, he wanted to take over from his father, who retired in 1999. He officially settled in in 2002. He started new Saumur cuvées and above all created his own wines by practicing parcel vinification while his parents were assembling their harvest. He currently manages the estate with 3 year-round employees and seasonal workers. In 2005, he began to age Chenins in barrels and then in 2017, he acquired sandstone jars to diversify his winemaking methods.

The vineyard is “a living, autonomous and diversified organism”.

The estate comprises 16 cultivated hectares, half of the vines in place being over 60 years old. They are spread over 5 hectares in the commune of Forges in the Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée Saumur area and 2.5 hectares in Les Ulmes and the other plots in the commune of Meigné-sous-Doué under the AOC Saumur Puy-Notre- Lady. Clay-limestone and clay-loamy soils, “which give more freshness and minerality to the grapes than other soils such as shale for example.”

9 different grape varieties are grown on the estate: chenin, chardonnay, sauvignon, cabernet franc, cabernet sauvignon, gamay, grolleau noir, grolleau gris and pineau d’Aunis. A diversity also chosen in order to diversify the result of the wines each year.

Honey flowers in the vines to attract insects and promote the diversity of yeasts, green manures, earthworm juice… All the care given to the vines is done with respect for nature and following the latest innovative research and conclusive.

In the cellar

“Agrobiology is for us a way of extracting from each terroir its typicality and its natural richness.”

From the cultivation of the vines, to the vinification and the sale of the cuvées, everything is done at the estate. Breeding is done without input. The real taste of wine, without artifice! It is only at bottling that a little sulphites are added. The wines undergo gentle vinification. With the exception of the crémant, the wine is vinified on the plot, which gives the 17 wines produced at the estate a character and an authentic originality which allows us to have a very diversified clientele. Stainless steel vats, barrels and sandstone jars also make it possible to vary the aging period of each wine, which can go up to 18 months.

A philosophy of innovation

On land that has not received insecticides for more than 40 years, and constantly questioning the work of the winegrower and the vine, Jean-François Régnier frequently participates in new projects for the development of wine specifications. or techniques that aim to improve the relationship of the winemaker to his vineyard and produce wines suitable for all palates. In his practice, he very regularly anticipates the reactions of the wine, he dialogues with the vines… “I like to experiment, to try to get the best out of the vineyard and to renew and develop my practices. The climate and our environment are constantly changing, the winemaker must adapt to these variations.”

“I was born on a barrel.” — Fabien Duveau

Fabien Duveau

Fabien says this with a wink. But it acknowledges his position as the 8th generation of the family to make wine in Saumur-Champigny and his dedication to his profession. Fabien regards his region, distinguished by its tuffeau bedrock and singular microclimate, as “one of the jewels of the Loire.” Here he holds some 40 parcels of chenin blanc and cabernet franc, a pair of varieties that enthrall him. As Fabien observes, “We always do better and with rigor the things that fascinate us.” Lately, that has meant drilling into the character of his single parcels.

Having worked among these parcels his whole life, he intuits the temperament and inclinations of each. Since taking over the domaine from his father in 2008, he has converted all of the family holdings to organics, a move he regards as his decisive thumbprint on the domaine. His “desire for clean farming and the preservation of the natural heritage” extends to his cultivation of biodiversity in and around the vineyards. In the cellar, his minimalist approach results in wines that express “the complex nature of the land and the know-how of its winemakers.” His intuition, dedication, and innovative perspectives infuse his wines with a freshness and delicacy that mark them as vibrant, eloquent examples of what Saumur-Champigny wines are at heart.

Growing up, Fabien “always knew” he wanted to be a winemaker. Since childhood, he worked alongside his father and grandfather since childhood. He studied at the nearby lycée, then left home for a stage in Bergerac, four years at Château Grand Corbin-Despagne in St. Émilion, and later a harvest internship at Rutherford Hill in Napa. He returned to Saumur-Champigny to take over winemaking from his father, guided by a shared view that “wine is first and foremost a pleasure and a generosity.” Now Fabien and his wife, Emmanuelle, jointly manage the domaine, supported by a two-person vineyard crew. Beyond wine, Fabien is ardent about Latin American dance. He feels “dancing and wine are two passions that have no connection except passion itself. Our profession is above all our passion.”

Saumur-Champigny

Fabien makes his wines in a cave dug in the 14th century from the same stone that later went to build the great Loire chateaux. The caves were first used as dwellings for the Saumurois, but the constant chill and humidity levels they harbor are friendlier to winemaking and storage than human habitation. The domaine, in Fabien’s family since the late 18th century, now spreads over 20 hectares within the roughly bounded triangle of Saumur-Champigny — to the north by the Loire, to the west by its tributary the Thouet, and to the east by the Fontevraud forest. The appellation is divided into communes, “very precisely grouped, according to strict geological criteria,” Fabien notes. He and Emmanuelle live in Chacé, and their vines are there and in the communes of Varraind and Saint-Cyr-en-Bourg.

The name Champigny derives from the Latin Campus Ignis (fields of fire), a reference to the relative heat of the microclimate, the warmest in Saumur. Crucial to the freshness of the wines is, Fabien notes, “the land’s ability to store this heat by day and diffuse it by night.” Being positioned at the eastern edge of the maritime zone tempers extreme heat during the growing season, but raises temperatures substantially in the winter. Protected from Atlantic moisture by the Mauges hills to the west, Saumur-Champigny vineyards see some of the driest conditions in the region, with Saint-Cyr-en-Bourg the most arid.

A low plateau of tuffeau, the yellow-white calcareous rock so distinctive of the central Loire, rises at the eastern edge of the town of Saumur and continues southeast, running under Fabien’s holdings. Tuffeau retains water as other limestones do, but drains more effectively, protecting against hydric stress while releasing water to the vines as needed. Overlaying the tuffeau is a mix of clay and limestone. Fabien attributes the velvet tannins, vivid fruit, and arresting freshness of his cab francs and the radiant intensity of his chenins to this soil composition. His aim is to allow the personality of each parcel to come through clearly in his wines.

Vineyards and farming

Farming organically and encouraging biodiversity in and around the vineyards are integral to Fabien’s approach. At about the time Fabien converted the family holdings to organics, Saumur-Champigny growers were banding together to establish Ecological Zone Reservoirs (EZR) — border areas of bushes, trees, and creepers, designed to provide year-round shelter, food, and breeding sites for helpful insects, birds, and animals. “Proximity to the plot encourages exchanges between the EZR and the vine. Grasses around the plot and the presence of vegetation between the rows accentuate these exchanges,” Fabien explains.

In the vineyards, Fabien has a mix of clones, though his oldest plots are of massal selections. All training is guyot and yields are carefully controlled. Vine age varies considerably from plot to plot. For his two single-vineyard bottlings, Clos de la Côte cabernet franc and Poyeux chenin blanc, vines are 60 and 25 years old, respectively.

Fabien is the first producer to differentiate between Upper and Lower Poyeux. (Clos Rougeard made this site famous, but they have only ever bottled Poyeux.) Fabien makes a distinction based on soil composition, elevation, and orientation, which leads him to take a different course in the cellar as well. (He’s also the only producer we know of that releases a chenin from Poyeux.)

Les Hauts Poyeux sports the famous Poyeux sand, which runs to a depth of 60 cm before hitting the first clays. Fabien gives this wine a long maceration, or as he says, ”essentially an infusion” allowing the aromatics to be linked to this soil texture. Aging for 12 to 18 months further sublimates the aromatics and refines the fine tannins of the terroir.

Les Bas Poyeux is lower, with shallow (20 cm) sandy soils over clay and limestone. This gives the limestone an opportunity to shine through. Fabien uses concrete vats and barrels to tease out the depth and complexity of this site.

The richness of this terroir is also expressed in the Duveau chenin. The successive soil layers (sand, clay, limestone) give the white Poyeux its roundness, complexity, and minerality.

Fabien calls himself “the most ardent believer in cabernet franc,” for the variety’s characteristic flavors and complexity, “always fruity, with varying degrees of smooth tannins, offering a delicate bouquet of red fruits with notes of violet and iris.” Some parcels give wines like Origine, which has such freshness Fabien thinks of it in terms of light and air. Others give more powerfully built wines that confound expectations of Saumur-Champigny. Fabien is also obviously a partisan for chenin, “the best grape variety in the world because we can make all kinds of wine, but always with a lot of subtlety.”

In the cellar

“If we have good grapes,” Fabien explains, “the most essential work is done. I’m just here to control my fermentation.” He strives to minimize sulfites and use only wild yeasts “because I am convinced that the yeasts naturally present on the grapes give the complexity and the originality to my different wines.” He matures his wines in the constant cool (12°C/53°F) of his cellar, using barrique: one-third new, one-third one-year, and one-third two years. For his single-vineyard Clos de la Côte, he picks at “big maturity,” with fermentation lasting between four and six weeks. For his Episode cuvée, he selects grapes with more pronounced tannins, then softens them with 18 months barrique elevage. Fabien believes correct serving temperature is essential to the appreciation of his wines: “Neither too cool nor at room temperature: 13°C [55°F] to 16°C [60°F] is ideal.”