La Boussole : A franco-german wine project,

to reveal majestic but still unknown terroirs

promoting the spirit of adventure

happily connecting people

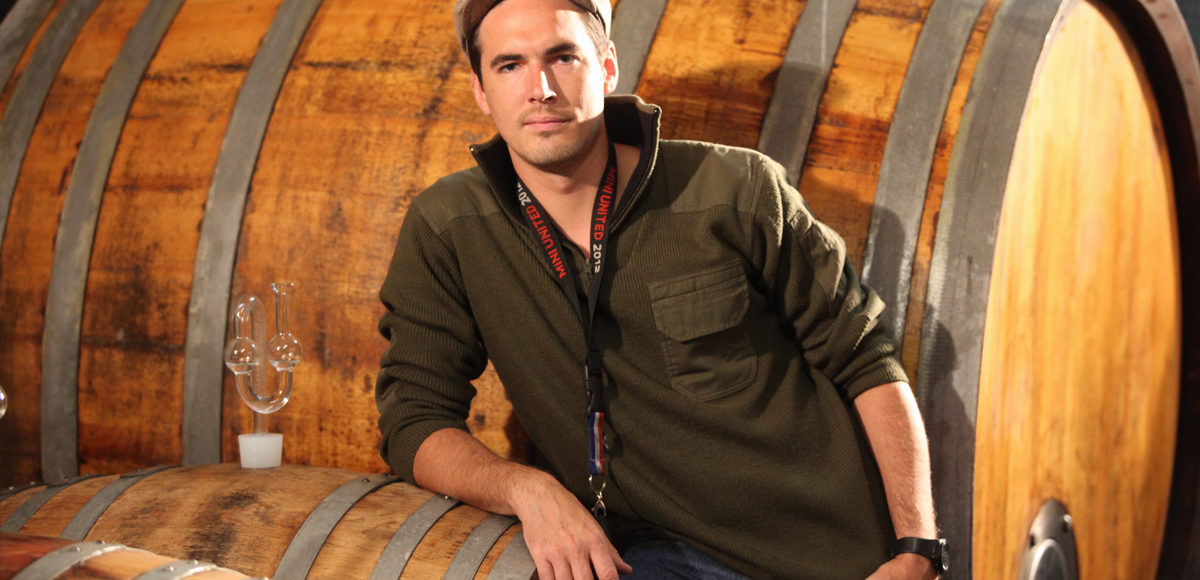

The idea of making our wine started a long time ago, when vinifying in Oregon for the crazy and impressive 00 Wines project. It had to be focusing on wine we love to drink, fine and elegant pinot and chardonnay, or cab franc and chenin, related to places we are in connection with. Above all, we wanted to make wine in a place in connection with the people we love, with charming and good terroirs, in a region where we could imagine set roots. As you know, roots are what a tree needs to grow and explore the sky.

In 2020, during my time working as cellar master – vigneron – man to do everything at Enderle & Moll, I met an amazing wine grower from Kippenheim, Thomas Kindle. He has heard about my self and was looking for someone able to support and help him to get out of the big local cooperative and start farming organic. The contact was excellent between us, his terroir in Kippenheim planted with chardonnay was looking amazing, and I loved the idea to support a global movement to more sustainable and healthy practices in vineyards.

This first time we met set the first stone of the project, and naturally gave the name. As a sailor – sail instructor- I am particularly sensitive to the idea of orientation, how navigation works, and how important a compass is to find a way at seas, or in life. The Name La Boussole was found.

Working at the same time for Enderle & Moll with the amazing human Manfred Enderle, an exceptional vine grower, farming pinot varietals on the huge limestone site of Frostberg in Münchweier, I could get from him a well selected plot to start my pinot noir production alongside the chardonnay.

With this two wines, I had the chance to continue experimenting in a more personal direction, inspired by my previous experiences full of Burgundian inspirations. Enderle & Moll was offering a full nature wine program, in which I wanted to bring clarity and better definition of the wines by working on some keys points in the processes. The Boussole wines where offering me a completing an different approach of winemaking.

2022 was the continuum of 2021, with an addition of a chardonnay from Lukas Krauß on a beautiful limestone soil site in the Pfalz, Osterberg. As an experiment, as a collaboration with a friend, wishing to learn and discover more about the german terroirs.

2023 was the end of the workrelationship at Enderle&Moll, and the opportunity to focus 100% on the Boussole project.

Life being what it is, I could start to work again with 00 Wines, as a winemaker-consultant this time, for their project in Burgundy and in Champagne.

Really engaged there, I am personally making most of the winemaking in Burgundy, and making sure the Grand Crus and Premiers crus of the project are made with the excellent and original methods we are using for the house of 00.

La Boussole is now in resonance with all the accumulated experiences and the dynamic learning process of being active on both German exceptional sites and atomic terroirs in Burgundy and the Cote des Blancs in Champagne.

The First trial in production are one chardonnay and one pinot noir from the 2021 vintage, called respectively NORD and SUD, which are the most important directions to know when you’re looking for a new path, at seas and in real life.

As second lecture level, we want the Boussole project to carry the values of humanity and to carry the spirit of adventure.

Humanity because wine is all about humanity. Connection between people, with nature and culture..

Spirit of adventure because life is all about that. Being open to the unknown, accept it and make the best to respect and understand what’s going on, on the terroir, in the cellar and in the world. Accept to try and take the risk to fail, and try again.

In a time of great challenges coming among all of us – climate change, politic & economic instabilities, paralyzing fear of a scary future in our occidental societies, we try to stay active and aware of the world, having clear views of what we want to live and try to do it.

“To grow up along the Ahr is to be infected early with the passion for Spätburgunder.” — Julia Bertram

“Nothing fascinates me like mature wines!,” exclaims Julia Bertram, herself vintage 1989. “The development, the changes, the complexity of aromas. This is why my wines are made for a long life. Old vines, low yields, carefully hand harvested (and not too late), with native yeasts and a long, gentle elevage in wood are important to me for this reason.” For more than a century, Julia’s family, most recently her mother and aunt, have grown and made wine in the tiny, marginal Ahr Valley. When Julia took over the estate in 2017, she directed her focus first toward the cherished old family sites, then on gradually stringing together an intricate necklace of what are now 11 sites along the River Ahr. She organically farms a total of 6.8 hectares of precipitous slopes, on soils mainly of greywacke, loess, loam, and slate, all planted to Spätburgunder (pinot noir, in German). Julia is fortunate to have a mix of rare old Ahr, Swiss, and French clones, including some planted by her grandfather. “What makes our wines unique,” Julia explains, “is the combination of slate and Spätburgunder in such a northerly region.” Single vineyard bottlings showcase Spätburgunder’s capacity for complex, long-lived statements of what this noble grape can achieve at upper latitudes. Across the board, Julia’s wines impress with their slender elegance, their arresting coolness and clarity, and above all a precisely mapped sense of place.

Region

The Ahr is one of Germany’s tiniest (560 hectares) and — critically — most northerly (50° N) wine regions, long held to be, as one writer would have it, “the winegrowing North Pole.” Yet the region offers vines an exceptionally warm, dry growing climate, with ample sunshine and little precipitation. “Even the Romans understood the special climatic conditions in the Ahr Valley: the little river flows west to east and so creates many south-facing steep slopes, the perfect exposition, protected from bad weather by the Eifel mountains,” Julia explains. The slopes, ranging between 100 and 260 meters [330 and 850 feet] above sea level, are predominantly of slate and greywacke. The dark soils readily absorb and reradiate heat, while the Ahr itself tempers the cold and circulates air to protect vines from spring frosts and deter botrytis — a major struggle in most steep vineyards, where vines are so difficult to access. Against this background, the Ahr’s relative obscurity comes as something of a surprise, particularly its derogation to the category of “lesser districts” in classic works on German wine. But relative obscurity only enhances the excitement of exploring such a singular corner of the wine world.

It is thought that red varieties came to the Ahr as early as the Middle Ages and that Pinot varieties came later still, some time after the Thirty Years War. Today, the Ahr is planted almost exclusively to red grapes (despite its tiny size, this is Germany’s largest contiguous red wine region), predominantly Spätburgunder as well as an earlier-ripening pinot strain called Frühburgunder. In the 19th century, political and economic instability, coupled with phylloxera, forced many Ahr Winzern to emigrate, and the area under vine was nearly halved between 1883 and 1925. The demands of heroic viticulture became insurmountable for many, until Flurbereinigung (vineyard reorganization) arrived in the 1950s, and with it the widespread planting of high-yielding pinot clones to shore up the Ahr’s flagging fortunes.

History

“The estate was founded in 1910 by my great-grandfather,” Julia relates. “At the time, the family farmed 2 hectares of vines, but even the previous generation had been engaged in wine growing as members of the local cooperative. My grandparents focused their work on the steep slopes of old vine Spätburgunder. In 2014, I decided to follow in the footsteps of my mother and aunt and become the fifth generation of our family to lead our little estate in the heart of the village of Dernau. In this way, I founded my ‘own company’ with just 1.3 hectares of vines that my parents made available to me. Each year, I’ve expanded a little so that we can have generational change of a different kind. In 2017, I took over the organization and leadership of the entire operation. Our team is mostly made up of family members: my aunt is in charge of direct sales, my parents are often out in the vineyards and my husband Benedikt supports me in the cellar,” Julia explains. Benedikt, it should be noted, is Benedikt Baltes, one of the most acclaimed Spätburgunder producers in Germany (also a Schatzi!). He, like Julia, grew up in the Ahr, but then followed his pinot passion east to Churfranken, where he took over the crumbling Weingut der Stadt Klingenberg, whose terraced slopes are home to legendary Spätburgunder terrain. Benedikt now splits his time between his estate and with Julia in Dernau — even more so since the recent birth of their son. Their combined experience and shared focus on a single variety exponentially increase the expertise of these young talents.

Winemaker

“Growing up in the family business,” notes Julia, “I was often in the vineyards and cellar, always with my finger on the pulse of the estate. But the real passion for wine and viticulture came with my first glass, when I was about 15.” Inspired, she interned at Dernau’s iconic Meyer-Näkel, pioneers of the great dry Spätburgunder largely responsible for elevating the Ahr’s profile over the past decade or so. Julia went on to study viticulture and oenology at Geisenheim, graduating in 2012. The following year, Julia was named German Wine Queen, an honor reserved for charismatic, intelligent women who typically come from winemaking backgrounds and are on track for a future in wine themselves. Wearing this crown, Julia spent a year representing German wines around the world. “That was when I first realized a wish to lead the family business into the next generation.” In 2014, Julia returned home and started to make a small amount of wine under her own name. Around the same time, she started helping Benedikt to establish his estate in Klingenberg, Churfranken — more than 200 kilometers away — while simultaneously building up her own. “The Ahr is where my roots and the foundation of my estate lie. Thanks to my parents, I have the opportunity to live out my fascination with Spätburgunder from the old vines in the best sites here. Working in and with nature, the different challenges in each year, and the versatility make the job unique for me. For us, it’s all about Spätburgunder, not just professionally, but personally as well. We also enjoy trying wines from around the world. Our second passion is riesling and since we have good friends in the Mosel, we are always well cared for in that department,” Julia adds.

Vineyards and farming

Julia has holdings in some of the Ahr’s most privileged vineyards. Among the Ahrweiler sites, the Rosenthal is regarded as a grand cru, with a south-/southwest exposition and grade of up to 45%. Soils are mostly of greywacke (a course, dense sandstone), with high proportions of clay, quartz, and feldspar, dating to at least 250 million years ago. The neighboring Forstberg is more southwesterly facing, nearly as steep, with soils that are a mix of sandstone and loess with a proportion of greywacke. Around Dernau, there is a greater concentration of Devonian slate, which comes to the fore in sites like the Schieferlay (Schiefer = slate, Lay = cliff) and the Goldkaul, the latter tucked into a small, very narrow side valley with a full southern exposure, extremely steep terraces, and soils of an exceptionally fine conglomerate of slate and greywacke — all untouched by Flurbereinigung.

“Our vineyards are planted exclusively to Spätburgunder. We have a very wide variety of old German clones as well as Swiss and French clonal material and vines from massal selection. The vines are almost entirely Guyot, with a small portion in single-stake training, as well as a trial with gobelet.” Julia’s intensive focus on one variety across a range of micro terroirs gives her an exceptional understanding of Spätburgunder’s proclivities and expressions in the Ahr. “Due to the steep slopes, this is mostly accomplished through hand work and thus a very close connection to the vines,” she recognizes.

Relative to her parents’ and grandparents’ approaches, Julia says “today we place a bit more emphasis on preserving the old vine parcels, consistent yield reduction, an even earlier harvest to retain more freshness and acidity in the wines, planting cover crops throughout the vineyards and, with that, sustaining great biodiversity as well as conversion to organic viticulture. In recent years, we opted against sowing cover crop seed mixtures, in order to give the natural growth the possibility to establish itself. Of course, we try to adjust our work to climatic conditions. It quickly becomes clear that there is no patented formula, that every vintage is different. To respond to the somewhat warmer vintages, we undertake less deleafing, or when we do, only on the shaded side, and are making trials with truncated canopies to delay ripening. In the past years, we have worked very closely along organic lines. But in 2019 we decided to convert all our vineyards systematically to organic viticulture.”

In the cellar

“For me,” says Julia, “90% of the quality is grown out on the steep slopes and our task in the cellar is to help express the elegance and complexity of the vines in the best way. By working very gently and without any additions (chemical or otherwise) we give our wines the opportunity to develop themselves. In the cellar, we work to capture and convey the quality we achieve in the vineyard with as much purity and authenticity as possible.”

As a rule, all of the wines are made in the same way: cold soak for three to four days, followed by spontaneous fermentation in open wood or stainless steel tanks, in contact with the skins for approximately 10 days (depending on the vintage), very gentle pressing, and with the wine then moved by gravity into cask, where it typically spends a minimum of 12 months. For the Handwerk bottling, the wines generally see six additional months in stainless on the fine lees. The Ahrweiler and Dernauer Spätburgunder see 75% neutral wood (300L and 500L casks) and 25% first- and second-use casks. Julia is very particular about her casks. She sources them from wood grown in the forests of Churfranken and made by coopers she knows personally, favoring a selection of ages and sizes. “The wood cask is always the means to an end, never a transmitter of flavor,” Julia makes clear. “Pinot from slate is unforgiving of the incorrect use of wood.”

“The various soils of the Ahr Valley, above all the slates in all their forms, determine the particular style of my wines,” notes Julia. “My pinots often have very fine, almost floral aromas and show an elegant minerality and a cool, elegantly juicy acid bite, which leads to very sensual and long-lived wines.” Julia’s philosophy is: “the closer the origins, the higher the quality. This is why we have categorized our sites into Erste (premier) and Große Lagen (grand cru) sites, although we are not part of any association or controlled system.”

“That things would be hard for us was clear. What we hadn’t expected was that they would also bring so much joy.” — Angelina and Kilian Franzen

Angelina and Kilian Franzen’s story is every bit as moving as their wines. It begins in the Mosel’s Bremmer Calmont. After millennia of cultivation, these sheer vertical vineyards — among the world’s steepest — had, by the 1980s, been abandoned. One wine grower embraced the daunting prospect of recultivation: Ulrich Franzen. “His vision was to bring the Mosel Terraces, especially the Bremmer Calmont, back to where it once was: at the top of German wines,” explains his son, Kilian. Tragically, in the middle of this heroic project, Ulrich lost his life. Kilian and his future wife, Angelina, then still students, returned home to take over the estate. Today, the Franzens have 5 hectares in the Calmont and holdings in the venerated Neefer Frauenberg and Kloster Stuben vineyards nearby. The focus is, naturally, riesling, with small plantings of elbling and pinot varieties. Vines are up to 90 years old, their roots driven into the terraced slate, giving immense concentration to the wines. Perhaps because so much has been forced in the vineyards and in the Franzens’ young lives, nothing is in the cellar. Fermentations are spontaneous, some taking nearly two years to complete. The wines go through malo and GGs are bottled late. All this accounts for wines that are as much about texture, herbaceousness, and salinity as they are fruit. They display remarkable freshness and animation as well as power and echoing length. Because so little wine is made from the Calmont, the wines have largely remained a secret, even among riesling connoisseurs. Through pure dedication and heart, the Franzens have made it the source for some of the most arresting wines in all the Mosel.

History

Wine growing in the Mosel valley dates to around 280 AD, when Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius Probus lifted the ban on cultivation outside what is now Italy, and cultivation spread throughout the Rhine and the Mosel. The Mosel Terraces form a unique landscape, very different from that of the more famous Middle Mosel. Topography and soils are paramount here. The microclimate is warmer, the vineyards more vertiginous, and viticulture more difficult here. The hand-built terraces that give the region its name have always been essential to enabling vines to grow in the cold macroclimate and steep terrain.

Even the Romans called the Bremmer Calmont mons calidus, hot mountain. By the 19th century, the Calmont’s suitability to riesling had become obvious: the entire mountainside was planted to riesling. The upper portion, known as the Fachkaul, was awarded the highest classification on tax maps of the time. Yet after WWII, lack of manpower and will to meet the intensive demands of the vineyards led to abandonment of these parcels, one by one. By the 1980s, the mountain was covered in roses and wild vines; only the parcels along the road and river remained under cultivation.

The Franzen family has been rooted in Bremm for centuries. Kilian’s grandparents had parcels in the Calmont. Kilian says it was always the dream of his father, Ulrich, to have productive vines up there again. “When my father took over operations from my grandparents in the early ‘80s, he changed the orientation of the estate and put the emphasis on the production of dry, lower-acid wines. Beyond that, the preservation of the steep sites was dearest to his heart.” In 1999, Ulrich resolved to buy all the contiguous Calmont plots he could. Napoleonic law had long since splintered the vineyards into tiny parcels, all with different owners. The only way to find out who owned what was to comb through town records. It took Ulrich three years to track down 112 different owners — from Australia to China to the U.S. — and purchase their plots. This enormous effort yielded a glorious prize: the steepest parcels, united in a magnificent, south-facing amphitheater in the very heart of the Calmont.

Painstakingly, Ulrich and a small team cleared and replanted the vineyards, all by hand. Within three years, they had anchored nearly 8,000 riesling vines in the obstinate slopes. The only concession to mechanization was the installation and operation of vineyard monorail lines — 500 meters of track ascending from the Mosel’s edge to the top of the Fachkaul.

This work “was my father’s life’s dream,” Kilian recalls. But before it could be fully realized, a tractor accident claimed Ulrich’s life in 2010. “Completely overwhelmed after the death of my father,” Kilian recounts, “Angelina and I took over the winery from my parents. We were in the middle of our studies and would have loved to travel after finishing. Instead, we came directly from Geisenheim to Bremm.” But the last thing you’ll hear from Kilian and Angelina are complaints: “Even though the maintenance of the steepest vineyards in Europe is one of the most physically demanding and intensive tasks we have, the preservation of this cultural landscape and continuation of hundreds of years of tradition fills us with pride and motivation every day. We tumbled into the adventure of our lives and know to treasure every moment of it.”

Winemakers

Angelina and Kilian were childhood sweethearts who went on to be classmates at Geisenheim, a winemaking team, husband and wife, and now parents to a young daughter who, in Kilian’s words, “is our life.”

Angelina is from Bullay, two villages downriver from Bremm, and her connection with winemaking runs just as deep as Kilian’s: “My family has also been involved in viticulture for many generations,” she explains. “My father has a winery a few miles away. My father’s cousin is Rita Busch, the wife of Clemens. It was many years after I decided to become a winemaker that I realized what an important role Clemens and Rita Busch play in German viticulture. But it was my parents and brother who shaped my path. My father has always mastered the profession of winemaker with 100% passion and rarely showed me the difficult sides. My brother went the same way and I saw every day how happy he was with it. My mother and stepfather have always supported me. I was always free in what I do and I chose the most beautiful profession in the world.”

At first, Kilian seemed set to tread a different course: “My parents put a lot of energy into the recultivation and suffered a lot. For me it was clear that this work is not just sunshine. So I decided to study something else. But when my parents reaped the first fruits after recultivation, I knew: that will be my life, too. I did not have to ask my wife if she was going this way with me: there would never have been another way for her.”

When Kilian and Angelina were called home to take over the estate, Kilian says, “For a while, we tried to balance study and the winery. Unfortunately, that did not work very long.” They hired Angelina’s brother and asked Kilian’s uncle and other winemakers to “show us how everything works.” It was a very difficult time. “The sadness, the terrible autumn of 2010, the setbacks.”

Little by little, Kilian says, “We learned and we grew in our tasks. We exchanged views with many winegrower colleagues. No matter if Reinhard Löwenstein, Clemens Busch, Johannes Leitz, Julia Bertram or Benedikt Baltes. Everyone stood by us in word and deed.” They have now made Franzen truly their own — though they are the first to give credit to everyone else.

“Today we have a job that requires a lot of time,” Kilian explains. “If we make some free time, then for our daughter. She is our happiness. She explains the world to us and opens our eyes every day. We are the fifth generation to make wine here, and hopefully she is the sixth.”

Region

Bremm sits about midway between Bernkastel and Winningen, at a point where the Mosel pulls into a tight bend and the Calmont rises imperiously above its north bank. The Calmont itself stretches some 2 kilometers (1.2 miles), forming what is essentially an enormous concave mirror, open to the south. The mountain rises some 400 meters (1,300 feet) above sea level, and its summit, covered in trees and shrubs, shelters the valley from northern winds and cold. To stand at the Mosel’s edge and look up at the Calmont, the cliff appears “almost threatening,” Kilian acknowledges. “Many passages, even steeper than 65 degrees, rise almost vertically. The steepness can only be grasped once you climb into its terraces. There is no single contained vineyard, but rather sections of earth, intermingled with steep rock walls and rough ledges. To make the cliff useful for cultivation, growers built terraces with support walls. However, these walls, unable to withstand the pressure of the mountain for long, collapse, and must be constantly repaired or rebuilt.” The terraces are also essential for retaining the sun’s warmth to moderate diurnal shifts and for guiding the vines’ root systems into the slope.

You would think such terrain would have earned the wines of this region renown, not obscurity. But, as Kilian explains, “the Calmont remains a secret among wine connoisseurs, partly because its size yields tightly limited quantities. Everywhere in the world, the Mosel is known for its steep slopes and riesling grown on slate. However, Mosel does not equal Mosel. There are countless flat areas on the Mosel with hardly any slate. But if there is a place that is 100% steep slopes and Mosel slates, it is the Calmont. There is no better situation for riesling.”

Vineyards and farming

The Franzens’ vineyards are concentrated in the Calmont, with additional holdings in the Neefer Frauenberg and Kloster Stuben just opposite. The Frauenberg and Kloster Stuben (the former Augustine monastery that thrived here for six centuries before secularization) are sited on a hilly peninsula formed by the Mosel’s hairpin bend, offering a second, though less dramatic, bank of south-facing vineyards.

“We now have a little more than 10 hectares in total — about 5 just in the Bremmer Calmont. The largest single parcel is the Fachkaul, with its now 1.8 hectares. Bremmer Calmont has about 12 hectares in cultivation. The remaining seven hectares are shared by about 20 other winemakers,” Kilian notes.

The Calmont vineyards are dominated by quartzite and red slate, the color coming from oxidized iron content. The ground here warms faster and stores heat better than elsewhere in the Mosel due to the optimal exposition, numerous rocks and walls, and high percentage of stone in the soil. Kilian points out: “The slate stores the sunshine during the day and releases it to the vines at night. Throughout the terraces, the foliage walls cast no shadow so each leaf can absorb the heat.” The vines’ root systems struggle for water and cope with limited supply by giving lower yields and smaller berries, making the Calmont wines in Kilian’s words, “a bit more powerful, a bit wider, and with a little more character.”

By comparison, the Frauenberg has more weathered gray slate, with more humus and smaller rock fractions, making the Frauenberg wines, as Kilian sees it, “finer, with slightly more fruit and finesse.” This is also where the Franzens have their oldest vines, ranging from 60 to 90 years old. For the estate wines, such as Quarzit Schiefer, Kilian “likes to take the vineyards from the part of the Calmont exposed a bit east. The wines are a bit clearer, a little less complicated, and a bit easier to drink.” Kloster Stuben is a lower, sandier site, well suited to the earlier-ripening traditional variety of the Lower Mosel: age-old elbling.

“We spend a lot of time and work in the vineyards. It all starts with well thought out pruning, lots of foliage and ground work,” explains Kilian. “In older vineyards, we still have a lot of single pole training. In the newer vineyards, we have moved to wire frames.” For the moment, Kilian says, “climate change is still OK for us. Every year we adapt to the current weather. If it is hotter and drier, we leave more leaves on the sunny side and take them away on the shaded side. If it rains a lot, we give the vines more possibility to dry quickly by more defoliation.”

No roads lead through the Calmont, only narrow paths that wind across the mountain and stairways that climb over the terraces. “Machines could never be used. On the back of the wine grower, fertilizer is transported up in the spring and grapes carried down in the fall,” Kilian makes clear. “The effort of the wine growers is arduous and the expenses involved with the cultivation and preservation of the vineyards on the Calmont have always been high.” To do this work is truly a calling. “We prune, tie, harvest, then fill about 60,000 bottles of wine each year — and love every single one of them. Our life is a succession of many small and some larger, often dramatic, events, which the vines store as information in their grapes,” Kilian muses. “These moments leave traces in our riesling.”

In the cellar

“When we took over the winery, we wanted to do everything differently. We saw only what we had newly learned at Geisenheim and wanted to upset everything. We had to realize that much of what was old was good. We did not stick to old data for the perfect reading time, but turned to the grapes. We reap maturity rather than time. We want lighter, clearer wines that retain their character, not feel heavy. The wines should decide in which direction they develop — not us,” notes Kilian.

In the cellar, grapes are foot-crushed in large boxes and macerated for two to four hours. After that, Kilian explains, “we really try not to interfere in the fermentation. In healthy years, we like to work with mash time, press very gently, and allow the must to settle for one night. Then the clear must is poured into stainless steel tank and we wait until fermentation starts with the wild yeasts. It challenges us, requires patience and time. Of course it can go wrong -– and sometimes does. Our riesling “Zeit” is the best example of this. A wine can bubble for almost two years. But that’s OK for us. Sometimes the wines also taste difficult, my wife would say ‘awful.’ But so far, these have come to be really great wines.” Beyond this, there is no fining and SO2 is used to prevent oxidation. The estate wines are usually bottled between February and April, the vineyard wines between May and July. The GGs only after the vintage. “But even there,” Kilian cautions, “we do not always go to the calendar, but to the feeling. And the wine.”

The wines are nearly always dry. But, Kilian explains, “Every year, one tank takes forever, and what can we do? We wait and wait and if it doesn’t get dry, it must be where the wine wants to be.” In 2015, they decided to start bottling the results as “Zeit” (“time,” in English). Though extraordinary today, the wine harkens to a time when this kind of élevage was normal. The 2016 version fermented for more than 400 days.

A key element to this overall approach is allowing the wines to go through malolactic fermentation as well.

Malo in riesling

If you talk malolactic fermentation with 10 riesling producers, nine will say, “That’s not what we want in our wines. We like purity and finesse.” One will tell you, “Yes, our wines go through malo — if it’s what nature wants.”

Malo in riesling is completely misunderstood in the U.S. and possibly nearly everywhere else. People tend to think it dulls the precision for which riesling — above all of the Mosel — is cherished. Many also believe riesling’s high acidity to be inimical to the lactic acid bacteria that cause malo. You’ll hear a pH of 3 bandied about as the number below which malo “doesn’t happen.”

In fact, malo can and does. It is part of some producers’ expression of terroir and can contribute a rounder acid profile and richer texture to riesling. It’s also quite possible that malo occurs in riesling far more often than we or even the winemakers — not all of whom control for malo — know.

Malo is not a true fermentation at all, but a bacterial conversion of malic acid to lactic acid. The lactic acid bacteria are typically on the grapes when they come into the cellar from the vineyard. But, as in the Franzens’ case, they can also be in the cellar. Primary alcoholic fermentation and the addition of SO2 at crushing significantly reduce the bacteria population. But by spring following harvest, nutrient and free SO2 levels typically have tipped back in favor of the resurgent bacteria, just as cellar temperatures begin to climb to a hospitable degree, allowing malo to occur.

There is much more at play than pH alone: Temperature and rate of fermentation. Timing of malo relative to primary alcoholic fermentation. Lees exposure. Early versus late bottling. And of course, timing and levels of SO2 additions. These factors can partially or fully block malo or alter the perceptible sensory effects of malo on the wine.

In discussions of malo in riesling, most consideration is given to its effects on acidity. According to research reported by Jamie Goode, malo increases pH by 0.1 to 0.3 units and reduces total acidity by 1 to 3 grams per liter. There are also concerns that it may add nutty or buttery aromas. But when managed correctly, malo can offer a desirable roundness of acidity and textural complexity. And malo’s characteristic aroma and flavor impacts, it turns out, can be absorbed by the lees, given adequate exposure.

(To be clear, here we’re only talking about spontaneous malo in dry riesling. Off-dry styles generally require SO2 additions for stability at levels that block malo.)

The Franzens are not the only Schatzis who let their dry rieslings go through full or partial malo: Stagård, Dreissigacker, and Knebel do the same. For their part, Kilian and Angelina say, “We work with malo. This is not really typical for Mosel riesling, but exactly what makes our style. Our spontaneous fermentation is very slow (up to 23 months). Our malolactic fermentation runs parallel to the alcoholic fermentation. It is part of our philosophy of giving the wines space and time. Ph is certainly one of the reasons for the malo. The other is the flora of lactic acid bacteria in our cellar. We have been doing malo for 30 years. The malo tastes and aromas are absorbed by the yeast. For us, the best case is if you do not smell or taste the malo at all.”

There is debate as to whether malo belongs to the historical style of the Mosel. Some argue that up until the 1890s, this was the norm for the dry wines. Others contend acidity levels of the time would have made this impossible. What matters to the Franzens is that malo is inherent to their terroir and style. They wouldn’t have it any other way.

“We want every vineyard, every site, each vintage, and even each cask to be allowed to show its own character and to observe its development. That means accepting what we have been given. In this way, we’re committed to the ideas of natural wine.” — Matthias Knebel

If you reach the Mosel Terraces by train, you’ll find your face involuntarily pressed to the window, staring in disbelief as you make the slow bend around the base of an impossibly sheer wall of slate and vines, rising almost from the track edge itself. This is where the Knebel family has been growing grapes since 1642. And over the centuries, it hasn’t gotten measurably easier to do so. Today, Matthias Knebel’s fidelity to painstaking, handwrought viticulture is yielding extraordinary results across his range, from a ridiculously undervalued village bottling to the magnificent GGs. The wines deliver the unadulterated intensity of these warm, slate-packed terraces, with an emphasis on texture, minerality, purity, and supreme finesse.

Region

The Mosel Terraces are distinctly warmer and even more formidable than the Middle Mosel just a few river bends away. Here the river valley narrows and the terraces climb, chiseled step-like into the slate and quartzite banks. The terraces make it possible for grapes to grow where it would otherwise be too sheer and stony to farm, while their form helps ensure the vines’ development by guiding their root systems into the slope. However, they are also quick-drying heat traps. This aspect was once a vital asset, but these days, they pose a danger of encouraging excessive ripeness. Ripeness can lead to the roundness and high alcohol levels that are anathema to Mosel riesling. Matthias and an influx of younger producers are countering this, in part with a serious commitment to sensitive farming wherever possible. It’s a movement that is transforming the region from almost moribund to kinetic right before our eyes. “Respect for a wine culture that has melded the slate, the steep slope, the river landscape, and the grape variety into a single entity in a centuries-long process,” says Matthias, and it is this philosophy that sets the Knebel wines apart.

Matthias Knebel

As a child, there was no doubt in Matthias’ mind that he would become a winegrower like his father, Rheinhard. But as a teenager, Matthias had second thoughts. He saw first hand just how grinding the work could be. Ultimately, he was convinced by the magic of wine itself and made the decision to follow family tradition. Rheinhard passed away unexpectedly in 2004, just as Matthias was to begin his studies at Germany’s top wine school, Geisenheim. These were sad, difficult times for his mother, Beate, for Matthias, and for everyone who had known Rheinhard. Being the strong woman that she is, Beate carried on in Rheinhard’s absence and took charge of the estate for the next four years. In 2008, Matthias returned from his studies and, together with interns and temporary staff, began carrying out Rheinhard’s legacy. By 2016, his work and vision had earned the estate VDP membership.

The total focus at Knebel is riesling. And the particular joy of the wines comes from Matthias’ feel for allowing the grape to translate the specific idioms of each of his parcels. Within these sites, every terrace has its own microterroir, influenced by a high variation in soil composition, exposition, and vine age. From Hamm come wines of herbal spiciness; Brückstück, concentration and elegance, Röttgen, fruity forcefulness, and Uhlen, succulent density. These sites are legendary among lovers of steep-slope riesling. From vintage to vintage, the wines have vaulted in complexity and finesse, resonance and vibrance as Matthias attunes himself to the character of each parcel and the demands of farming these sites in a warming world.

Vineyards and farming

Blessed with a collection of old vines, some un-grafted, Matthias relies on fewer canes, natural competition, lower yields, and rigorous selection. In 2012, he gave up all chemical herbicides in the terraces and the estate hasn’t used fertilizer in decades. “My parents did a great job, so I didn’t need to reinvent the wheel,” says Matthias. Because holdings in Winningen tend to be smaller and more scattered even than elsewhere in the Mosel Terraces, the handwork these sites demand is monumental — easily double the number of man hours needed to tend flatter vineyards.

In the cellar

Matthias’ objective — “deep Mosel rieslings with fine elegance and powerful expression” — is realized across the range: even his basic riesling is sourced entirely from the terraces. Only perfectly healthy, ripe grapes are used for the top wines. This serious selection process is the reason hardly any wine was made in the 2013 vintage, for instance. Preferment skin contact is occasionally employed depending on the site and quality of the vintage. All of the wines are fermented spontaneously.

Matthias prefers stainless steel as the primary vessel for vinification and aging as he feels it best expresses his nuanced terroirs (and for a guy working on his own, are, helpfully, very easy to clean). Generally speaking, malolactic fermentation is avoided, but much like maceration, is determined on a case-by-case basis. Extended lees aging completes the depth and balance of the wines.

“We see ourselves as accompanists to our wines,” says Matthias. “Accompanying an idea, an objective, a concept of style. But we like to allow singularities, edginess, particularities to come through. We want every vineyard, every site, each vintage, and even each cask to be allowed to show its own character, to observe its development. That means accepting what we have been given: not making a big vintage leaner or a lean one heavier. In this way we’re committed to the ideas of natural wine.”

Konz could be seen as a quaint, sleepy valley village in the Saar, surrounded by rolling vineyard hills, pastures and small houses with one modest church steeple–though it is anything but old-fashioned when Max von Kunow is around. Since assuming the estate in 2010, Max has nearly doubled von Hövel’s vineyard holdings, converted the estate to organic practices (including an intensive compost program) and he is in the process of transforming not only the viticulture, but also the style of the wines. Max’s father, Eberhard, preferred swift pressing of the grapes; Max is now working with some skin maceration, especially for the drier range, and a slower, gentler crush for the fruity range. In fact, a dry range really did not exist at this estate until Max arrived because his father did not prefer them. The wines destined to be fruity are less opulent than in vintages past; they are more crystalline and crunchy. In keeping with the organics practiced in the vineyards and the longer hang time prior to harvest, Max encourages indigenous yeast fermentations for all of his wines.

That’s a lot of change for such an iconic Saar estate in a short period of time, but Max is like a Tasmanian devil, wanting everything to evolve as quickly as possible. He seems up to the challenge! “Saar wines could be the best riesling on planet earth,” Max will tell you directly without any hint of irony or sarcasm. He is serious and he’s also a schatzi.

The 21-hectare von Hövel estate operates out of a manor house that was completed in the 12th century, where it initially served as an abbey retreat for the famous wine monastery of St. Maximin in Trier. Located in Konz-Oberemmel in a side valley of the Saar, which is known as Konzer Tälchen (“little valley” of Konz), the old cellar is today as it was over 800 years ago. The winery was inducted into what is now the von Kunow family in 1806 when it was purchased by Emmerich Grach—son of a well-to-do chandler and the great-great grandfather to Max von Kunow—the estate’s current proprietor. Grach was an assistant and deputy mayor of Trier, an influential businessman, and a well-known Weingutsbesitzer, or wine estate owner. In 1803 he purchased Maximinerhof in Oberemmel and renamed it Weingut Grach, alongside several other well-known estates in the region after Napoleon secularized the vineyards of the Saar and Mosel from the churches and monasteries. Grach’s son Johann Georg became owner of Maximinerhofgut, which later went to his grandson-in-law Forstmeister Balduin von Hövel, a head forester from Prussia and good friend of Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Von Hövel’s great-grandson is Eberhard von Kunow, whose parents bought the estate in the 1950s, at which point the winery began operating under the von Hövel family name. Eberhard von Kunow, Max’s father, owned and operated the von Hövel estate from 1973 until 2010 when Max (the 7th generation) took over the estate with an impressive debut vintage. While Eberhard produced fruity-styled Prädikat wines, Max slowly began to increase the dry range of riesling in hope to round out a classic Saar portfolio; he seeks to produce gastronomy-driven wines.

After finishing secondary school in 1997, Max took an apprenticeship with Kruger-Rumpf in the Nahe region where he decided to follow in his family’s footsteps and pursue a career in winemaking. The following year he worked for Lucashof in Forst (Pfalz), spent time working in Burgundy and returned to Germany where he interned at the Salway estate in Baden; Max completed four apprenticeships before beginning his winemaking studies in 2002. For two years he studied oenology in Veitschöchheim and afterward went on to pursue an International Wine Business degree at Geisenheim. During his time at Geisenheim, Max worked for his family’s estate as well as for Karthäuserhof and Fürst Löwenstein. He graduated from Geisenheim in 2007 where he worked as an export manager for the Wirsching estate in Iphofen (Franken) and in 2008, moved to Luxembourg where he consulted for 34 private winemakers. He returned to the family estate in 2010, when his father suffered an unfortunate stroke, jumped right in and as it turned out, achieved great success with his inaugural vintage; he was recognized by Gault-Millau as producing one of the top three Kabinetts (Oberemmeler Hütte) and the top Feinherb Riesling from the Scharzhofberg, both from the 2010 vintage. He took ownership of the estate the following year and has since nearly doubled their holdings.

Farming organically was a necessary transition for Max and he has taken it seriously. In addition to completely eliminating the use of herbicides, he propagates regional plants and herbs, prepares his own compost and spreads local straw, marc and raw fertilizer throughout his vineyards. As is the goal of most mindful growers, Max lets the grapes hang as long as possible to ensure they reach—and in some cases exceed—physiological ripeness, or as Max refers to it, “mineral ripeness”; the Saar is the coolest and most windy region in Germany and often requires a longer hang-time than in warmer regions of the world. He avoids botrytis for the dry range but sometimes includes it for the Prädikat bottlings.

When the grapes enter the cellar, Max separates the fruit that he feels is destined for skin maceration (anywhere between 18-36 hours) from the rest in which undergoes gentle crushing before entering the press. Wines are fermented in either stainless steel tanks or neutral wooden 1000 liter Mosel fuder casks. All of the wines ferment spontaneously.

The von Hövel estate has ownership in the following vineyards, all of which are planted exclusively to riesling: Oberemmeler Hütte (5.8 ha), the famed Scharzhofberg (2.8 ha), Kanzemer Hörecker (0.6 ha), Oberemmeler Rosenberg + Rosenkamm, Krettnach Silberberg and Niedermenniger Euchariusberg. Hütte, Herrenberg and Hörecker are all monopoles of the estate.

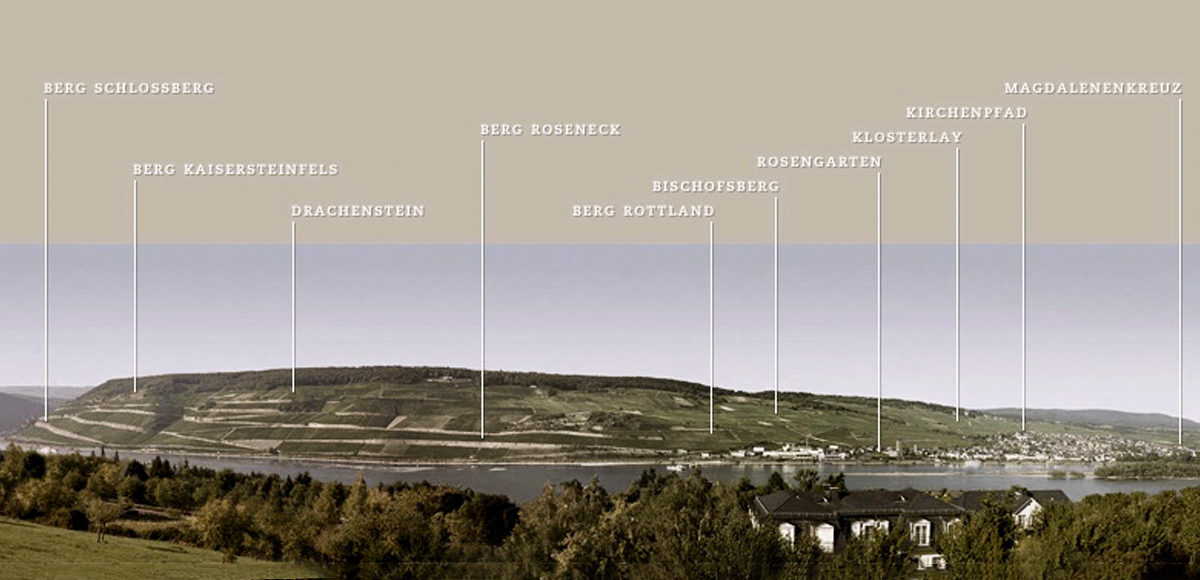

Under the direction of Johannes Leitz, Weingut Josef Leitz has earned the reputation of being one of Rheingau’s top growers and moreover, one of the finest producers in Germany. Since taking over his family estate in 1985, Johannes has grown his holdings from 2.6 hectares to over 40, most of which are Grand Cru sites on the slopes of the Rüdesheimer Berg. Once the home of some of the world’s most sought after and expensive wines, the region fell to mediocrity in the years following the Second World War. Josi has made it his life’s work to reclaim the intrinsic quality of his native terroir and introduce the world to the true potential of the Rheingau.

The Rheingau is a small region, stretching only 20 miles from east to west. It is marked by a course change in the Rhein River’s flow to the North Sea from its origins in the Swiss Alps. As the Rhein flows north along the eastern edge of the Pfalz and Rheinhessen, it runs directly into the Taunus Mountain range which has a subsoil comprised of pure crystalline quartzite. Rivers, no matter how mighty, are lazy and the Rhine has yet to break through the quartz infrastructure surrounding the town of Mainz. At Mainz, the Rhein turns west and the 30 km stretch between Mainz and Rüdesheim makes up the majority of the Rheingau. Even though the region is further north than the middle Mosel, its south facing slopes get hotter than the narrow Mosel Valley which therefore provides important diurnal temperature variation.

Leitz’s estate vineyards lie entirely on the westernmost part of the Rheingau on the Rüdesheimer Berg—a steep, south-facing hillside of extremely old slate and quartzite—planted entirely to riesling, encompassing the Grand Crus of Schlossberg, Rottland, and Roseneck. Leitz trains his vines in a single-cane, cordon system to improve the quality and character of the fruit, differing from the majority of Rheingau growers where the practice has long been to prioritize yield via a double-cane system. Johannes is a firm believer that the crucial work of the vigneron takes place in the vineyards. Focused on farming as sustainably as possible and working by hand, the grueling hours of labor on the ultra-steep slopes allow these ancient vineyards to reach their maximum potential.

After harvest, Josi is equally focused on working gently in the press house and ageing the wines on their gross lees. Johannes selects bottle closures to reflect, and more crucially serve, the individual cellar practices employed for each wine; Stelvin closures are used for wines raised in stainless steel to preserve freshness while wines raised in cask are bottled under cork to allow for a long development in the cellar.

With the 2011 vintage, Leitz began to designate the pre-1971 parcel names on select bottlings, reviving the individual voices of “Hinterhaus” (Rottland), “Ehrenfels” (Schlossberg), and “Katerloch” (Roseneck). He has also resurrected the once neglected site of Kaisersteinfels, which has become one of the most sought-after wines of the Rheingau. “Der Kaiser” sits high, just beneath the forest line of the Rüdesheimer-Berg, with a spectacular view overlooking the confluence of the Nahe and Rhein Rivers. The singular terroir on the westernmost point of the Rheingau is composed of quartzite, very old grey slate, as well as some iron-rich red slate and produces wines with incredible complexity and length.

In 2011 Johannes was recognized by the esteemed Gault Millau as “Winemaker of the Year.” We could not be more excited to be a small part of the Leitz project. We believe that these are some of the finest white wines in the world.

“I see the strengths of German wine as the finesse, depth, minerality, and precision of its aromas.” — Markus Spindler

In 1620, Sontag Spindler left Burgundy for the Pfalz — just as the Thirty Years War was making this a uniquely inauspicious time to resettle in the Palatinate. Almost impossibly, Spindler took the long view. He began to purchase vineyards and by the war’s end was able to acquire one of Germany’s most revered parcels, the Kirchenstück. In 1828, Spindler’s foresight was confirmed when this site was assessed at the highest tax rate in the land. But Napoleonic law splintered Spindler’s descendants’ holdings and the estate was evenly divided among three brothers. Since that time, Weingut Heinrich Spindler has taken its place among the great estates of Forst, with parcels in the Jesuitengarten, Pechstein, and Ungeheuer. None of this is lost on Markus Spindler, great-grandson of Heinrich. He carries forward the 20-hectare, certified organic estate with a level of skill and respect equal to the heritage and holdings entrusted to him. From his everyday bottlings to his top riesling crus, the wines are tactile, focused, detailed, and decidedly dry. They are about nuance and purity over power, grace and precision over opulence. Above all, they are meticulously wrought portraits of legendary terroir.

Region

With a startlingly Mediterranean climate, palm, fig, and citrus trees flourish alongside a wide range of grape varieties in the Pfalz. In and around the village of Forst, however, riesling reigns supreme. Here, a narrow swath of gentle south and east facing slopes rises behind the village to meet the Palatinate Forest, part of the largest contiguous woodland area in Western Europe and a designated UNESCO biosphere reserve. The Haardt Mountains, an extension of Alsace’s Vosges, shelter the vineyards from cold and curtain them from rain.

Forst’s top vineyards — Markus is blessed with tiny parcels in each — are some 120 to 150 meters [390 to 490 feet] above sea level, benefitting from morning sun and rising breezes. The sites are distinguished by their varying microclimates and soil compositions: colored sandstone, shell limestone, and basalt — deep, layered, and rich enough in clay to protect vines from hydric stress in this very warm, very dry region.

Colored sandstone defines the Pfalz, from the great red and yellow blocks of it that form the walls of Speyer Cathedral to the soils of the Mittelhaardt. The sandstone was formed some 250 million years ago, when ancient rivers laid down their sediment in a then desert-like landscape. Oxidized iron accounts for the red variant; thermal waters that washed out the iron account for the yellow.

Forst’s least expected feature is its outcrop of basalt. We can’t exactly call the Pfalz a volcanic region, but when the Rhine valley collapsed some 50 million years ago, magma was forced to the surface and cooled to produce black basalt stone. Basalt is a notable component of several sites here, most crucially Pechstein. Forst’s growers haven’t left it entirely to nature to distribute this prized element, though. For centuries, they’ve collected, then scattered basalt shards through their vineyards to help retain heat and capture the opulence and smoky salinity basalt can impart to riesling.

Although Forst’s vineyards seem predestined for riesling, until the early to mid-20th century, these sites (as with the rest of Germany) were largely planted as field blends. But, according to Markus, in Forst, the percentages of other varieties, mostly silvaner and gewürztraminer, were uncommonly low and by the 20th century, riesling was varietally labeled. More recently, sauvignon blanc has also made its mark on the region and Markus takes it every bit as seriously as his riesling.

Winemaker

Family life is the heart of the winery, where Markus and his wife, Lola, live with their three young children. Aside from family outings in the Pfalz Forest, Markus’ passion is for Alpine sports – climbing, mountaineering, and biking – which, he says, comes from his grandfather. “Beyond that, nature is very important to me. I draw a great deal of energy from it.”

Markus wasn’t always sure he wanted the life his ancestry indicated for him. In 1996, he started off with apprenticeships close to home at Dr. Deinhard (now von Winning) and Friedrich Becker, and in the Saar with the legendary Egon Müller. He went on to fulfill a civil service tour, then did a year-long stage at Schug in Sonoma. Putting some time and space between him and the family estate gave Markus perspective: “I needed the distance to realize what a treasure we have at home.” He returned to Germany and enrolled in the country’s top wine school, Geisenheim. “I have always been fascinated by the aging potential of the riesling grape. So I asked the wine chemistry department if I could do my thesis in this area. This led to a study of approximately 30 wines from eight vintages, with particular emphasis on the analysis of volatile aromatic compounds.” He also undertook further apprenticeships, most notably with F.X. Pichler in the Wachau.

In 2007, he graduated and returned to Forst, to work alongside his father, Hans. Eleven years later, Markus took full responsibility for the estate, which includes a well-regarded Gutsausschank (“like a taproom, but for wine,” Markus modestly translates) in which his brother Florian’s acclaimed cooking is matched with bottles from the Spindler cellar.

Vineyards and farming

To walk the Spindler parcels is to hear the echo of history and feel the power of terroir. It is best to start with the Kirchenstück, a 3.7 hectare clos directly behind the village church (Kirche); of which, Markus has a 0.28 hectare sliver. The low sandstone walls around it absorb the sun’s warmth and gradually release it at night, gathering warmth and ensuring air movement that safeguards the vines from frost. The soils here are sandstone scree, sandy clay, and basalt, all planted strictly to riesling. The best wines from the Kirchenstück are a dialectic of finesse and complexity, elegance and power, succulence and structure.

The origins of the name Ungeheuer (“monstrous” in English) have long been debated, but Markus cites the most convincing: “The vineyard was first mentioned in official documents in 1470, as the ‘an dem Ungehuwern.’ In the parlance of the time, this referred to the ‘unsettled and unsettling’ nature of this area west of Forst.” Wild no longer, this vineyard rests on a wide range of soils, dominated by clay and limestone. It is one of the largest Forst sites as well as one of the driest and warmest, but thanks to a significant proportion of deep clay, vines stay cool and hydrated. Markus has a choice 1.5 hectares in a steeper, limestone reef section. “Cool air flows in nightly from the woods,” Markus explains, “extending the ripening period for the grapes and boosting aromatic development.”

The Spindlers have under a hectare in the vineyard that, as Markus says, “riesling lovers love”: Pechstein. The name means “pitch stone,” referring to the basalt in this 17-hectare site, which translates into rieslings of density, with an unmissable smoky-salty intensity. There is a phenolic component — “like quince or grapefruit” — to the rieslings grown here, but they are “always clear and deep in their minerality,” Markus notes.

According to the famed 1828 tax classification, the second-best site in the Pfalz is the little Jesuitengarten. Here Markus has just 0.26 hectares on rich loam, colored sandstone, and basalt. A slate layer ensures a healthy channeling of water from the mountains to this site.

Markus regards the 8.6-hectare Musenhang as “one of the best vineyards of this category,” an Erste rather than Grosse Lage. He has a 0.33 hectare slice that he prizes for “its cooler microclimate, strongly influenced by the nearby forest, where ripeness is good but never excessive, and where limestone soils show more structure and minerality.”

The Spindlers have been committed to farming without herbicides, pesticides, or synthetic fertilizers for nearly 20 years. Markus officially converted to organic viticulture in 2012, an easy and natural transition as all the groundwork had already been laid by his father.

“I think if you want to make top-level wines with character, the basis is healthy soil with a great variety of microorganisms, insects, and a high humus. It’s important to me to have an ecosystem in my vineyards with variety, both above and below the soil,” Markus explains. “Homemade compost, diverse cover crops, and strictly biological plant management techniques are essential for us. Our intensive use of compost — including pomace, straw, and horse manure — allows us to deal with heat and drought when they come.”

Markus is responding to climate change with more sensitive canopy management, removing leaves only on the north side of the plant, and making a very thoughtful, focused use of cover crops. “This is really important,” he notes. “We have a mix of 50 different crops to give the soil a nice structure and to protect it from tractor compaction. We only cover every other row due to competition for water and mow the cover crops only in case of drought.”

All the top sites are hand harvested with multiple pickings.

In the cellar

Markus’s highest objective — “to make wine with filigree depth” — may sound like a paradox. But it is that tension that makes the wines so arresting. “In the vinification, we use maceration, skin fermentation, native yeasts, battonage and new wood. However, we approach all of these enological steps with Fingerspitzengefühl” he says, using a German term that encompasses instinct and touch. “Precision, minerality, and fruit character are not to be lost.”

Not surprisingly for someone who wrote his thesis on the evolution of aromatics in aging rieslings, Markus sees his greatest challenge in the cellar as “preserving the full range of natural aromas.” To achieve this, grapes are pressed gently, at low pressure, with limited use of pumps and maximal reliance on gravity. Macerations are short, fermentations start with ambient yeast, though cultured yeast may be added to ensure the rieslings finish fully dry. Markus prefers long, cool ferments in stainless steel and neutral Stück (1200L) and Doppelstück (2400L) oak casks. The wines remain on the fine lees, with occasional batonnage, until they are bottled between February and June after harvest. Attention to every facet of the process is obvious from the everyday estate riesling, sourced from holdings in and around Forst, to the arresting and expressive single vineyards. While his village-level Forster Riesling is raised in 80% stainless, 20% neutral cask, the single vineyards vary, dependent on site, but tend to be fermented and raised entirely in stainless, again with the emphasis on capturing the panoply of nuanced aromas. Markus wants his sauvignon blancs to be of a drinkable, fruit-driven style. “By staggering the harvest in various stages of ripeness, we get a sauvignon blanc of complexity and variation, on the one hand with green, very fresh aromas, and on the other, ripe, complex fruit, leading to an incisive wine of structure and length.”

“My passion for wine and what is connected to wine has not changed. Solely my imagination, to go from young, innovative winegrower to a classic, has grown.” — Joachim Heger

Just a few miles from the French border, in Germany’s southernmost region of Baden, Joachim Heger farms a pair of extraordinary volcanic grand crus (Grosses Gewächs): Ihringer Winklerberg and Achkarrer Schlossberg. The vineyards here are on steep, sun-soaked slopes, places of startling intensity. Joachim gives voice to this terroir through classic varieties, foremost the pinot family, riesling, and silvaner. In recent years, German pinot noir (Spätburgunder) has come into much sharper focus. There’s no getting around the work Joachim has done — over close to 40 vintages — to revolutionize the way we interpret this variety and its potential on these unique volcanic, loess, and limestone soils. The results are wines of unmistakable depth and deliciousness, age-worthy benchmarks for Baden and for Germany.

History

Joachim’s grandfather, Dr. Max Heger, was a country physician with the luck to live in the little wine paradise of Ihringen. His patients, primarily local wine growers, sparked his interest in making wine himself. The vineyards he acquired on the Achkarrer Schlossberg and Ihringer Winklerberg were, even then, widely acknowledged as the top sites of the Kaiserstuhl. In 1935, he founded the Dr. Heger estate. Fourteen years later, his son Wolfgang, known as Mimus, took over. It was he who brought the estate to the forefront of German winemaking — thanks to his world-class sites and dedication to quality at a time when this was not the rule for Baden’s wines. In 1981, Mimus handed the job of cellar master to his son, Joachim, who has brought great imagination, inquiry, and spirit to the role ever since.

In 1986, Joachim and his wife, Silvia, faced a fresh challenge. Joachim explains: “Wine prices in those days were very low. It was not possible to realize a profit from the steep slopes and small terraces. The techniques and winery equipment were outmoded. We had to act to carry out necessary investments and changes and to employ skilled staff.” In response, they founded a second estate, Weinhaus Heger.

Today, the Grosses Gewächs and Erste Lage wines are made under the Dr. Heger label, while Weinhaus Heger is larger and includes long-term partnerships with other growers, to give it a more flexible scope. Taken together, the Heger estates produce a remarkable spectrum of wines. As a Schatzi, Joachim has worked with us to find the best range to offer in the U.S.

Winemaker

Joachim was born in Ihringen in 1958. Growing up, wine played a decisive role in family life, and Mimus’s quality philosophy deeply influenced his son: “My father had a profound knowledge of winemaking, but also very good tasting skills.” Everything was in place for Joachim to assume the family profession — except Joachim himself. He intended “to become a country doctor, like my grandfather.” Though he started his enology studies at Geisenheim, his heart was still set on medicine. His wife, Silvia, was “the one person asking me: ‘Do you want to be the last in the family tradition?’ She encouraged me to think over the situation and finally find my vocation as a winegrower. Her dauntlessness and her down-to-earthness were a great motivation for me.” He returned to Ihringen, “and informed my grandma that I would become a winegrower and winemaker. I went back to Geisenheim to continue my studies with ambition.”

After graduation, Joachim gained hands-on experience at several estates. In addition to the crucial influence of his father, he was shaped by his friends, winemaking legends Helmut Dönnhoff and Wolf Salwey, and Herbert Krebs, head of the “Qualitätsweinprüfung” department at the State Research Station Freiburg.

Quite unusually for a winemaker of his generation, Joachim says travel and connections with peers from other regions have been key to his professional education. “A decisive role in my life as a winegrower has always been to be in a circle of close friends, all of them winegrowers. We have travelled to all important wine regions of the world. On these trips were Georg Breuer, Bernd Phillipi, Werner Näkel, Paul Fürst, Werner Knipser, Helmut Dönnhoff, Christoph Tyrell, Wilhelm Haag, just to name these. Those journeys were extremely fruitful and broadened the horizons of all of us. Helmut Dönnhoff said they were like school excursions. We were like pupils, insisting and curious. We tasted and exchanged our impressions and information with each other. We returned home with newer and deeper insights. It was most interesting for me to learn how different the international world of wine is from our Kaiserstuhl area.”

Most influential were the trips to Burgundy Joachim made with Franconian Spätburgunder pioneer Paul Fürst: “Burgundy opened a completely new perspective. We learned that all is about terroir, soil, and aspects. But also the importance of the growers’ absolute commitment to manual work and the steady and deep look into these components.” Joachim learned from the New World, too, with trips to the International Pinot Noir Celebration in Oregon, where he met, among others, Au Bon Climat’s Jim Clendenen, with whom Joachim enjoys “a great and inspiring friendship” to this day.

The Heger estates now bear the marks of this vast and sundry experience. Walking the vines with Joachim, you feel his passion for the land as he breaks down his terroir for you not just parcel by parcel but vine by vine. He is a gregarious, quick-witted, and intensely spirited guide. “My passion for wine and what is connected with wine has not changed,” Joachim muses. “Solely my imagination, to go from young, innovative winegrower to a classic, has grown.” Now Joachim and Silvia’s two grown daughters, Katharina and Rebecca, are both pursuing wine studies. “Every time I follow their engagement in wine and see how they form their views, I am happy,” says Joachim. “I am sure they will bring new elements and influence.”

Region

“Pinot noir has a very long tradition in Baden,” explains Joachim. “The first vines were planted in the year 884 by Emperor Karl III at Lake Constance. The production of high quality wines was interrupted and set back again and again in several wars during the last centuries. Yields were quite high and there were few outstanding wines.”

The Kaiserstuhl (named for its resemblance to an emperor’s throne) is a compact zone of some 4,000 hectares of vines planted around the stump of an extinct volcano. It rises above the Rhine river valley, just east of Alsace. Geologically speaking, it is a rare place indeed. Volcanoes formed here during the late Tertiary period, at the end of a long succession of eruptions, starting in the Cretaceous. Heavily eroded volcanic vents mark the landscape and the rocks that remain are of the Miocene, dating 16 to 19 million years before the present. These volcanic rocks are of alkali-carbonate structure and contain elements of magnesium iron silicate, which can be found here as the gem peridot, a crystalline material that weathers slowly and provides good drainage.

Adding to the uniqueness of the region, prior to volcanic activity, in the Jurassic sedimentary layers formed in the eastern part of the Kaiserstuhl that resulted in the creation of two distinct neighboring geological formations. On top of this diverse mother rock, at depths up to 40 meters [130 feet], are loess soils that were blown here after the last Ice Age from the northern Limestone Alps in modern-day Austria.

Climate-wise, the Kaiserstuhl is the warmest, driest place in Germany. Again, think Alsace. But here, almost bizarrely, among the vines, wild grape hyacinths sprawl and irises blossom. Figs, apricots, even orchids and wild cacti grow well, while rare butterflies and eastern green lizards thrive in abundance. It’s a magical place and Joachim knows how to let this speak through the wines.

Vineyards and farming

Many of Baden’s vineyards, hard on the French border, were destroyed in WWII. By necessity, the clonal material for replanting came from France. In the Wanne block of his Winklerberg vineyards, Joachim’s father planted a massal selection of Clos Vougeot vines in 1956. The Vorderer Winklerberg GG comes from a mix of Dijon clones, the precise composition a result of the Hegers’ own breeding and grafting work as well as genetics research at nearby University of Freiburg. While it’s recently become common to see growers focus on lower-yielding, higher-quality, terroir-adapted vine material, Joachim points out that “we’ve cared about the clones already for 20 years.”

Joachim’s focus has always been on maximizing the vitality of his vineyards. He works tirelessly in the challenging terrain, “experimenting all the time.” Since 2007, he has farmed all his vineyards without herbicides or pesticides, and — inspired by his good friend Clemens Busch — introduced cover crops. He tests innovative disease-resistant crossings and a range of organic fertilizers and treatments. His plot of old silvaner vines is horse plowed. “All these methods are essential tools for retaining and improving the fragile ecosystem of the vineyard,” he contends.

To focus on just three of Joachim’s holdings gives a sense of the great range of options he has to play with. The Winklerberg, called one of “the most privileged vineyards in Germany,” was subjected to deleterious enlargement under the 1971 German Wine Law. Fortunately, Joachim’s parcels are all within the original Winklerberg, with steep, sloped terraces, mostly southwestern exposures and shallow, weathered volcanic rock soils. The Schlossberg gives him a mostly south-facing amphitheater of steep banks of sparse volcanic and loess soils. The Tuniberg is a small, terraced hill that lies between the Black Forest and the Kaiserstuhl, its microclimate cooler and its soils tending to limestone and loess.

For Weinhaus Heger, Joachim sources grapes from his own vineyards and sites belonging to trusted growers with whom he has long-term contracts. He believes in “paying them more so we can convince them of the Ökobilanz,” which translates roughly to “profits on the ecological balance sheet.”

In the cellar

The Heger style ranges from fresh, snappy rosés done in stainless to profound old-vine silvaner spontaneously fermented and raised in neutral barrels, with full malolactic and very little SO2. For his flagship pinot noir, Joachim seeks clarity of site expression and freshness above all. The fruit is all de-stemmed and given a cold soak, à la Henri Jayer. The Erste Lage wines ferment in stainless, then are racked by way of gravity into a mix of new and neutral barrique. Grosses Gewächs bottlings ferment in 100% new, extra lightly toasted barrique, preparing the wines for a long life in the cellar yet making them hard to resist in their youth. In addition, Joachim also makes some Erste Lage weiss- and grauburgunder from both the Winklerberg and Schlossberg. These selections redefine the potential of pinot blanc and gris in this place and are among the most delicious, unique whites of Germany.

“Our aim is to conserve every facet of what our vineyards produce. In our opinion, each wine documents its origin, its soil, the efforts of the winegrower, the weather, and the details of an entire year.” — Benedikt Baltes

If you’re looking for the wines of Benedikt Baltes, you’re in the right place. His work, his ideas, his singular focus on the extraordinary Spätburgunder (pinot noir) of Churfranken are as integral to the estate as ever. But in the decade since he took over the old vineyards and cellars of the City of Klingenberg, much has changed. Critically, the conversion to organic farming throughout the terraced, red sandstone vineyards, but also a focus on native yeast fermentations, local oak, an unrelenting quest to define Spätburgunder’s identity — and fatherhood. Benedikt and his partner (fellow Schatzi!) Julia Bertram now have a small son. Their life together is in the Ahr, where Benedikt grew up and where Julia’s family vineyards and future winery are. So, while Benedikt remains the guiding force at Steintal, more hands have come on deck. What hasn’t changed is the attention the estate rivets on Spätburgunder. The wines are singularly cool, slender, taut, and sculpted. This is because Benedikt thinks of them not in terms of other reds, even Burgundy, but of riesling. “Good pH, fine extraction, and reductive methods” are, he says, crucial to achieving the level of finesse and detail that mark out the wines. He’s convinced that Spätburgunder needs an “autonomous identity” and few in Germany are working as thoughtfully or brilliantly as he to resolve that definitively. The wines have an alluring strength, with delicate fruit and aromatics, grip and depth. All reward patience, or at least a good, long decant.

Winemaker

Benedikt was born and raised in the Ahr, where his family has long supplied grapes to the local co-op. He had other ambitions. After studying economics and enology, and interning in Austria, Hungary, and Portugal, Benedikt set out to find vineyards where he could make his own mark and push himself as a vigneron. It was impossible to find land in the Ahr so Benedikt scoured the country for a terroir in which he could drill down on Spätburgunder. He eventually found his way to the historic town of Klingenberg, in Franconia, with the opportunity to buy an ancient “urban winery” (founded in 1601—clearly ahead of its time!), with 10 hectares of old vines on steep, red sandstone terraces. “Life is short. You get maybe 40 vintages, so you need to go a region where the vines are of a certain age, where the previous generation understood where to plant. Old vines, good sites were important to me. I always thought I would start very small, with 2 or 3 hectares. But when I saw what the old Klingenberg winery had to offer me, I knew it was a dream come true.”

Starting fresh offered Benedikt the unique opportunity to enact his vision without being hamstrung by expectation or tradition. He also happened to have the great luck that climate change and improved understanding of Spätburgunder’s specific needs in the vineyard and cellar coincided with his arrival in this special place.

Benedikt brings a questioning spirit and tremendous energy to his pursuit of pinot perfection. “There is no preconceived notion he does not challenge,” notes Master of Wine Anne Krebiehl in her guide, Wines of Germany. “Ripeness? Trellising? Sustainability? He seems to relish challenges, and is actively experimenting, testing, pushing boundaries to see what will work.”

In keeping with this maverick outlook, Benedikt has learned “at least as much about Spätburgunder from Riesling estates as I have from top Pinot estates,” as he told Krebiehl. “Spätburgunder has such a different tannin structure from other red varieties and my winemaking aligns more and more with white wine: good pH, fine extraction, reductive methods. German Riesling is a fine wine with moderate alcohol, its long ripening period affords it enormous saltiness. It has an autonomous identity. Working out that identity is what is happening to Spätburgunder now.” He explains what fascinates him about the variety: “Riesling and Pinot Noir just offer more room for projection, more canvas to portray what happened in a vintage. I grew up in the Ahr with Pinot Noir, so I found my fun in that grape.”

In 2018, Benedikt was joined by Carl-Julius Cromme, who brings an international business background, including studies at Geisenheim, to Steintal. He interned under Benedikt, then returned to take on operations and marketing. He’s now stepped into the role of managing director, with the full intent of furthering Benedikt’s vision for Steintal.

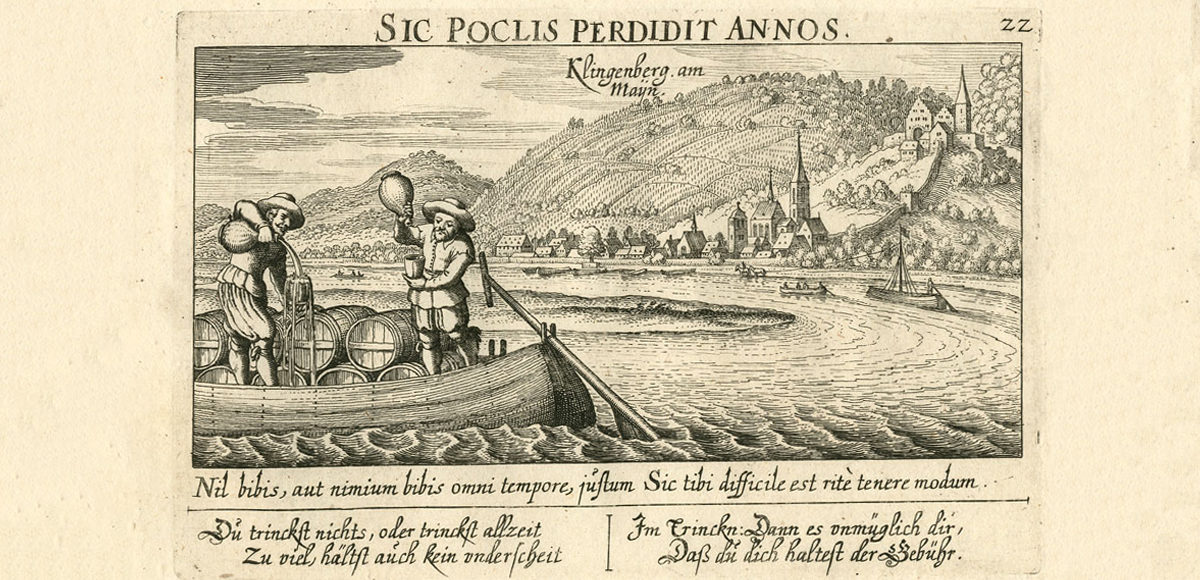

History and Region

Weingut Stadt Klingenberg, founded in 1912, had been a thriving municipal winery with its own lauded vineyards. But by the time Benedikt took it over in 2010, revitalization was in order. He relished the chance. Churfranken, a small red wine oasis in northwestern Franconia, is still quite obscure, even among serious connoisseurs of German wine. The first written mention of viticulture in Klingenberg is from the 12th century. By the 17th, there was evidence of wines from the area being consumed in surrounding cities and exported as far as the Royal Court of Karl Gustav of Sweden. Today, Spätburgunder grows on steep, terraced slopes that soak up the sun — crucially, as Klingenberg sits at nearly 50 degrees north latitude. The brick-colored stone retains heat, insulating the pinot vines when nighttime temperatures plunge while its high iron content gives the wines a dusky minerality.

Vineyards and farming

Steintal now encompasses 12 hectares of terraced sites — all protected historic monuments —primarily on two slopes: Klingenberger Schlossberg (Große Lage / Grand Cru), with 25-60 year old vines, red sandstone in the steep terraces and tremendous diurnal temperature shifts that give the wines a unique combination of elegance, herbal notes, and a cool, minty minerality. Großheubacher Bischofsberg (Erste Lage / Premier Cru), with 20-40 year old vines, again on terraced red sandstone. Unlike the profoundly rocky and stony Schlossberg, this site has a sandier topsoil but the mother rock is still pure, red sandstone. The wines from the Bischofsberg are a bit more fruit-driven and charming in their youth. All sites are planted to French and German clones, propagated by massal selection. In Klingenberg and Großheubach the German “Ritter” clone predominates, while in Bürgstadt, the Dijon clone comes to the fore.