Cascina Melognis

Revello’s mountainous austerity requires you to redraw your mental map of the Piedmont. Sawtooth, snow-capped Monviso, one of the highest peaks in the Alps, dominates the landscape. This is not the hilly green terrain shaped by the Po, but rather the river’s high Alpine source. Although Revello is just 45 km (30 miles) from the heart of Barolo, its separation by a broad plain and its distinctly cooler, wetter climate have evolved a very different, deeply individualist tradition of wine. Fittingly, Cascina Melognis is a tiny winery called into existence by the vision and will of two determined individuals, Michele Fino and his wife, Vanina Maria Carta. Michele’s roots in farming and the land, coupled with their shared dedication to proving the potential of an historic but little known terroir, has, in rather short order, begun to deliver captivating results.

History

“We are a domaine with a very poor history,” Michele laughingly acknowledges. “The activity we can properly call ‘winemaking’ started in 2008, when we found a few amazing vineyards in Saluzzo.” Today, Michele and Vanina organically farm 3 hectares of vines in and around Revello and Saluzzo, in the area known as Colline Saluzzesi, tucked in the far northwest corner of the Piedmont. They focus on a handful of varieties native or traditional to the region: pelaverga, barbera, chatus, and pinot noir. “The vineyards that we currently manage were cultivated for domestic consumption only by our relatives and the owners of the ones that nowadays we conduct,” Michele notes.

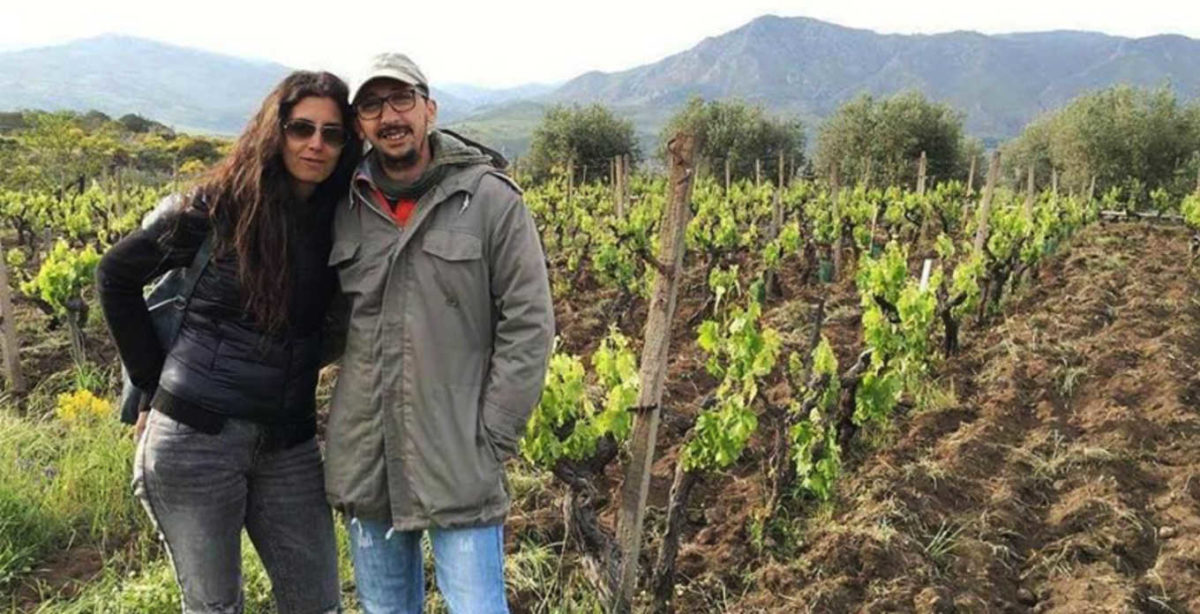

Michele and Vanina

Michele was trained as a lawyer and holds a PhD in Roman law, but “became a winemaker out of passion and a grower because I didn’t want to be the first man of my family not to cultivate a piece of land. All the Finos have always been farmers and/or breeders.” Michele’s interest in winemaking has its roots in his civil service duty in Roero 20 years ago, when he met a number of winemakers who ultimately inspired him to follow their lead. Michele is self taught, but has learned much from long-time collaborations with other Piedmontese winemakers, while Vanina gained wine experience working at Rocche Costamagna, in La Morra.

Revello and the Colline Saluzzesi

Michele and Vanina and their three young children live and work in Revello. “Working so close to a mountain peak almost 4,000 meters (12,000 feet) above sea level shapes our climate, our behavior, and our wines. Our winemaking activity is deeply rooted in our terroir,” Michele explains. “The landscape is modeled by glaciers, the soils are millions of years older than those of the better known Piedmont hills — very rich in rock, gravel, and sand, very poor in nutrients, but extremely rich in minerals. The soils are therefore adapted to let the vines grow slowly, limit yields, and guarantee specific aromatic evolution of our grapes.”

In the vineyards

The Cascina Melognis vineyards are at 350-500 meters (1150-1640 feet) above sea level and are farmed in accordance with the requirements of these high elevations, as well as the poor, acidic soils, stark diurnal shifts, and cool, wet climate. “We have changed very little from the past,” Michele says. “The oldest vineyard was planted in 1947, the youngest in 2002. Our philosophy is naturally low yields. That means Guyot training and minimal or no nitrogen fertilizations.” Michele and Vanina are now completing the third year of conversion to organics, in anticipation of certification. At harvest, the family, bolstered by a wider cast of relatives, does all the picking by hand.

In the cellar

The red wines are spontaneously fermented in stainless steel tanks and undergo malolactic fermentation. All processes occur at ambient cellar temperature, which, given the climate and elevation, is quite cool. Divicaroli (100% pelaverga) ages six months in stainless tanks, while Ardy (70% barbera/30% chatus blend) and Novamen (a barbera-led blend with pinot noir) are aged for 18 months in first- and second-use French oak barrels.

The grapes for Divicaroli are sourced from 30-year-old pelaverga vines. Pelaverga grosso (distinct from the pelaverga piccolo variety of Verduno) is characteristic of the area around Saluzzo. Here it was long a staple in blends, but its importance shrank over time, until it nearly vanished in the 1970s. Today, careful site selection and pruning are bringing about a small and welcome renaissance for the grape. Its peppery, high-toned freshness, and delicate floral and herbaceous notes are quintessentially Alpine. It is still rare to find monovarietal pelaverga from anywhere in the Piedmont, let alone the Colline Saluzzesi.

Pelaverga is late-ripening, and Michele typically harvests in mid-October. The grapes are de-stemmed, then pumped into stainless-steel tank for fermentation and traditional punch down three times a day for the first nine days. After alcoholic and malolactic fermentations, the wine is delicately transferred to another tank for aging until April, when it is bottled.

Ardy is sourced from some of the oldest vines Michele and Vanina work with, 45- to 50-year-old barbera and chatus. Chatus is a variety native to the Ardèche, from which it has now all but disappeared. Today the grape is found almost exclusively in the vineyards around Saluzzo, where its spicy, herbal character make it an excellent blending partner for barbera’s earthy depths.

The barbera is picked in late September and the chatus in early October. The vinifications “take place separately but follow the same track,” Michele notes. De-stemmed grapes go into a stainless-steel tank where they start fermenting and undergo traditional punch down three times a day for 15 days. After alcoholic fermentation, the wine is pumped into another tank for malolactic fermentation. After this, the wine is transferred without pumps into barrels. “Depending on the vintage, we may keep the two wines separate, in order to mix the cuvée before bottling, or do it just before putting the wines into barrels,” Michele explains. “The wine is bottled after 18 months in barrel, and another four months in bottle.”

Novamen is a barbera-led blend with pinot noir, from vines that are roughly 50 and 15 years old, respectively. The grapes are picked in early and then again in late September. Again, the vinifications take place separately but follow the same track. De-stemmed grapes are pumped into stainless-steel tank for fermentation and punch down three times a day for 15 days. After alcoholic fermentation, the wine is pumped in another tank for malolactic fermentation. Then the wine is transferred without pumps into barrels. As with Ardy, after 18 months in barrel, the wine is bottled and then aged for another four months before release.

“Il Selvaggio means “the wild.” It was a word that many years ago an enologist said to me: “your wines are wild as you.” — Roberto Semino

The vines of La Vecchia Posta sit high in the Colli Tortonesi, in the village of Avolasca, amid the gentle foothills of the Ligurian Apennines. Here Roberto Semino cultivates 3.5 hectares of vineyard dedicated to native grapes of the Piedmont: the rare and glorious timorasso, sprightly cortese, bright barbera, and fresh dolcetto. The Tortoniano soils are ideally matched to this suite of varieties. Roberto was among the very first to farm organically in Italy, starting in the 1980s. His work with the land is based on a trust in nature and informed by a deep appreciation of biodiversity. In the cellar, he relies on spontaneous ferments, few to no added sulphites, elevage in stainless for the whites and tonneau for the reds, all to allow for the pure expression of the high hills and their proximity to forest, mountain, and sea.

History

“My family immigrated from the village to Tortona,” says Roberto, speaking of the region’s principal city, a scant 15 km away. “I was born and grew up there. But every summer I was in Avolasca with my grandfather. In that way my passion for agriculture was born. Then, in the ‘80s, I was at the cooperative Valli Unite.” Unite is a remarkable place, a self-proclaimed “subversive” coop of mixed agriculture and ecological education, designed to reconnect people with their planet. The experience proved transformative for Roberto. “After that I started to rebuild my farm — from zero.” Today La Vecchia Posta is a place where two breeds of indigenous cattle, a rampant vegetable garden and, of course, grapes grow together to sustain Roberto and his family, as well as the agriturismo guests and WWOOFers they host.

Region

“La Vecchia Posta is in Avolasca, a very little village in a nice place on the hills, 450 meters above sea level,” explains Roberto. “Behind the village you can see the Apennines between Piemonte and Liguria, so we often have a very nice view to the valley surrounding us.”

“As a winemaker,” notes Roberto, “the advantage of our region is the climate. Summers are dry and windy, with breezes from the sea, which also gives an atmospheric situation with unpolluted air. The big advantage of our region is that there is a very good biodiversity in agriculture and behind us there are enormous green spaces, woods and pastures.” Once in our area there was the sea, so the soil is rich in fossils and minerals. It’s a kind of soil with limestone and clay, called Tortoniano, one of the best for vineyard cultivation.”

“We planted timorasso because it’s the only autochthonous variety from Colli Tortonesi, an important white that can be aged for years — and a personal motivation is that my father loved it.” Timorasso was, along with cortese, once one of the two most planted white grapes of the Piedmont. By the end of the 20th century, the variety, prone to a host of cultivation challenges, had all but vanished. Walter Massa, also of this region, famously led its rescue from near extinction; now it is one of the most sought-after Italian whites: quite racy, distinctively herbal, floral, mineral, and high in acid, famously gaining depth and complexity about five years after vintage.

Roberto makes two bottlings: “Poggio Dello Scagno,” meaning “up near the stars,” from one of the highest vineyards in the area, and “Il Selvaggio,” or “the wild one,” from timorasso vines deliberately scattered throughout Roberto’s property. “The vine is a spirit that wanders between meadows and acacias, between rows and uncultivated, gathering in the wind all the aromas of these high lands,” he says. “’Il Selvaggio’ was a word that many years ago an enologist said to me: ‘your wines are wild as you’. Even if from that time many things have changed, the name remained. Every time we planted a vineyard, we put inside some rows of timorasso to see how it grows in different kinds of soil. Timorasso was abandoned in the beginning of the 1900s because is very difficult in the field, with a compact cluster, not a big producer. It is still difficult work with it, so you have to do much more hand work with leaves and clusters.”

“Derthona” is often added to labels to indicate timorasso wines of distinctive quality. “In one year,” Roberto explains,” we are going to change the name to Timorasso Derthona, which is the Latin-Roman name for Tortona. In this way we want to fix the kind of grapes with our area as Nebbiolo with Barolo or Cortese with Gavi — to protect our tradition since at this moment some famous producers of Langhe-Barolo are coming to invest here.”

The other stars of Roberto’s vineyards are cortese, of Gavi fame, which achieves a delicate intensity at the high elevations and in the silty, fossil-rich soils of Avolasca. Roberto coaxes a wonderfully perfumed, charming brightness from Dolcetto. His “Teraforta” bottling takes its power from the clay-rich soils dolcetto loves, and its freshness from well-ventilated, high-elevation sites. Roberto says this is the wine he loves best to pair with meals.

Vineyards and Farming

Vineyards elevations, hovering around 400 meters above sea level, are the key to the vibrancy of Roberto’s wines. Vines range in age from about 15 to 30 years. Trellising is Guyot, though Roberto says he favors pruning the vines “more as a ‘y’ to divide the energies coming from the roots.”

Farming in tune with the land it essential to Roberto. “We were working organic even before the country started to certify organic farms, so we were among the first in Italy to be certified and with the strange combination of alphabetic order (Avolasca), we have the certification code of “I1”, where the “I” means Italy and the “1” means that we are the first on the list.”

“To respond to climate change, we are starting with soil management, with some cover crops between the rows, part of the gradual lightening of the soil to let the few rains penetrate.” Careful canopy management and green harvests are further “operations that, together with the biological method, help us in the natural world in our qualitative growth.” Hand picking is a given. Grapes are transported to the press pad in small boxes to ensure they remain uncrushed, and therefore unoxidized, even on the short trip from vine to cellar.

In the cellar

“Our first aim is to harvest good grapes in the right moment, then we allow spontaneous fermentations starting with pied de cuve, low usage of sulfites (in some wines we don’t use them at all), no clarifications, and batonnage in all the wines.” With a mix of aging vessels — stainless, for the whites, and tonneau, for the reds — and a preference for lees exposure and even some skin maceration, as for the “Poggio” timorasso, the wines are the truest possible expression of place.

Marcel Zanolari

Valtellina clings to the stony reaches of upper Lombardy, where distinctions between Italy and Switzerland subsume to the forces of nature. This long, narrow Alpine valley, Italy’s northernmost wine-growing region, is characterized by imposing peaks, dense forests, and, as far as the eye can see, dry-wall terraces zigzagging across its steep north slopes. Over the course of two millennia, the terraces (laid end to end totaling twice the length of the Italian peninsula) have been built and rebuilt, always by hand — a monument to the unbroken resolve of generations to grow wine in this place. Here, on 10 hectares of vines above the single-steepled village of Bianzone and scattered along the valley further east to Tirano, Marcel Zanolari has dedicated himself to biodynamic farming and making “living wines.” Marcel believes “nature is at the center of all work and man is the respectful observer and carer of the delicate balance of the ecosystem.” Putting this conviction into practice in the vineyard and in the cellar yields wines that could come from nowhere and no one else.

It’s telling that Marcel deflects attention from himself toward something much larger —“connecting people, society, and land through sustainable agriculture.” It’s also what makes him a Schatzi. In talking with Marcel, it quickly becomes clear that his many passions, including hiking and paragliding, all tie in to his dedication to working with, not against, nature, and to sharing his learned experiences so that others can benefit. This approach has earned his estate Demeter certification, one of the strictest in biodynamics, and recognition as the first Italian winery to become a B Corp, a certification that requires adherence to rigorous social and environmental standards.

The estate

Marcel’s interest in winemaking started as a teenager, when he began learning from his visionary father, Giuliano Zanolari. “In the 1980s,” Marcel explains, “on two experimental patches of land, my father made the first attempts at cultivating vines with a method that avoids all synthetic fungicides. For about 15 years, he carried out his experiments on nebbiolo, pinot noir, and cabernet sauvignon vines.” Encouraged by this work, Marcel started a small farm in Bianzone in 2001. “At the beginning, I always told myself: Wait and see. About every ten years you will lose your harvest. Recalculating now, we have lost more than that” — including his entire crop in 2008. Over time, Marcel has added parcels in and around Villa di Tirano, Tirano, and Telio. Mixed crops and small livestock (geese, goats) are part of his vision for closed-cycle agriculture, though the terraced terrain makes these aspects among the most challenging.

The region

Valtellina is an east-west valley, whose south-facing vineyards have been planted to capture the region’s abundant sunlight, moderate rainfall, warm days, and cool nights. The Rhaetian Alps to the north shelter the vines, while a steady, gentle southern wind brings air flow essential to this humid river area. But viticulture would be impossible here without the terraces and their unique sandy, gravelly soils. Starting with the Romans, through to this day, the vineyards of Valtellina have depended solely on human effort for the thin topsoil that overlays the terraces. Over the centuries, laborers have excavated innumerable loads of riverbed soils from the valley floor and hauled them up, one by one, into the terraces — all in an unending effort to maximize the plantable vineyard area. Maintaining the terraces and their soils is a never-ending task, as both are prone to damage from heavy rainfalls (more frequent now with climate change) as well as training of artisans to do the work.

The staggering number of work hours required to farm vines here by any method, let alone biodynamically, has shrunken the vineyard area of Valtellina considerably in the last century or so. Countless vineyards have been abandoned to forests steadily encroaching from the hilltops. The average parcel size is now just .65 hectares. To counter this, Marcel works with a team of “local boys without vineyard experience but with more passion for the nature and wine” with the aim of inspiring them to keep the terraces in active use — an act of faith in the future.

The vineyards are overwhelmingly planted to nebbiolo, known locally as chiavennasca. Genetic research has revealed a wide diversity of nebbiolo clones in Lombardy, suggesting this, not the Langhe, is the grape’s original home. Valtellina’s main biotype is nebbiolo rosé, prized for its hardiness, including resistance to millerandage and berry shatter (useful in Valtellina’s cold, rainy springs) and to drought (frequent in the region’s dry, hot summers).

Sforzato (Italian for “strained”) is a local production method as much a part of the character of Valtellina wines as the vineyards themselves. In this process, select nebbiolo grapes are raisined for about three months in the appassimento method, over straw trellises in drying sheds. This process of concentration was once essential when not every vintage could be counted on to reach full ripeness. Now the tradition is carried on as a unique expression of the region.

In the vineyards

Roughly half of Marcel’s 10 hectares are planted to nebbiolo, with the rest divided among pinot noir, cabernet sauvignon, riesling, and pinot blanc, using disease resistant clones. Vine age ranges from 20 to 60 years. High elevations (350 to 750 meters, or 1150 to 2500 feet, above sea level) and sandy, gravelly granitic soils control yields. Vine rows are planted north-south to maximize sun exposure.

Marcel explains: “On our farm, we are inspired by the principles Rudolf Steiner suggested in the early 1900s to restore vigor to lands that were already impoverished and exploited at that time.” Since converting to biodynamics, Marcel has observed that his “soils have changed color and texture. There are no more problems of drought even in dry vintages because the soil is much more alive, requires much fewer treatments, and slowly gives more quantity year after year. The grape skins are healthier and allow very, very long macerations. They have a more vital and positive energy.”

“To embrace the biodynamic method means to accept a substantial reduction in productivity, especially to begin with as the balance between terrain and plant has not yet been restored. The choice of adopting the biodynamic principles in this initial phase of ‘unbalance’ is a risky one, especially in an area such as Valtellina, which is also conditioned by the asperity of the land. We can however overcome all obstacles by remaining strong in our fundamental ideals and being animated by passion, belief and motivation,” says Marcel.

In the cellar

Valtellina’s nebbiolos tend to be lean and sculpted, delicate and floral — paler, less tannic, higher in acidity, and altogether lighter on their feet than their more famous Langhe counterparts. Marcel works with, not against, this style. He is fascinated by traditional winemaking methods and unafraid to explore new ones. “It is not always easy,” he observes, “to obtain a ‘live’ wine that expresses all of its potential and shows the particular qualities dictated and influenced by the climate of the season,” but precisely that is his aim. “Often we have to learn again to discover lost flavors, in our case, those of wine.” Marcel is patient. He knows his wines are often initially closed, but with a few hours, they open. “The wine is always in motion.”

“All our wines are de-stemmed and undergo a process of maceration with the skins,” explains Marcel. “If the health of the grapes permits, we prefer long macerations, from a few days up to a couple of months.” Spontaneous fermentation happens primarily in steel tanks and amphorae. “In both cases we use the submerged-cap fermentation method. The length of fermentation depends on the year’s harvest and the development of the natural yeasts present on the individual grapes,” Marcel notes.

Marcel regards each of his wines individually. “Every typology requires its specific aging journey,” he explains. All red wines are aged for a minimum of 24 months, with additional bottle aging of about 12 months.

Nebbiolo Valtellina Superiore is sourced from vines that have been in production since 2001, some of which are air dried on the vine. Spontaneous fermentation is carried out in stainless steel tank, and after malolactic fermentation, the wine is transferred to second- and third-use barrique for 36 months of aging.

Sforzato Valtellina Superiore also comes from nebbiolo vines in production since 2001, dried in the local tradition, through which 25% of the grape’s water weight is lost. The partially dried grapes are then briefly cold macerated, spontaneous fermentation is carried out in stainless steel tank, and after malolactic fermentation, the wine is transferred to used barrique, as above.

Sforzato “Le Anfore” is likewise sourced from partially air-dried nebbiolo that is then raised in clay and cement amphora. Marcel has selected amphora for this bottling for the “correct roundness it gives to the wine, without introducing the scent of wood and its derivatives,” as he puts it, and for the vessel’s ability to maintain a cool constant temperature in normal cellar conditions.

Uvaggio Rosso is a blend of native and traditional red grapes that sees two to three years in used wood cask and amphora, followed by 18 months in bottle.

“We really believe in our two autochthonous varieties: schiava and lagrein. Our focus is on producing wines of good drinkability, elegance, and depth.” — Florian Ramoser

Florian and Georg Ramoser are the tight father-son team behind a sharply focused set of wines from schiava and lagrein, two native red varieties synonymous with Alto Adige/Südtirol. Untermoserhof, the Ramoser family home and winery that dates to 1640, sits just above Bolzano, where it looks onto the green depths of Val d’Isarco/Eisacktal and the staggering Alpine panorama just beyond. Schiava, the bright, floral main grape in the traditional St. Magdalener blend, and its more soulful partner, lagrein, are entirely in their element on the four hectares of tiny parcels clustered around Untermoserhof. Steep slopes, challenging varieties, and the Ramosers’ dedication to minimal-input farming demand rigorous handwork in the vineyards. Their concentration on old vines, dense plantings, controlled yields, and thoughtful cellar work is giving exceptional results — dense, spice-tinged lagrein and vivid, inflected St. Magdalener. They are vibrant, supremely drinkable expressions of a region that is realizing its full potential for wines of distinctive depth and elegance.

Untermoserhof

The estate was established in 1640, likely taking its name, as Florian explains, “from ‘Moser,’ a common name in the region for someone living near a bog” — marshland having been a feature of the river-riven Bolzano landscape centuries ago. From the start, Untermoserhof was a place of mixed farming, included vineyards; it remained so, by necessity, through the Ramosers’ acquisition of the property in the late 1700s right up until WWII. “After the war, as times slowly got better, my family wanted to concentrate on cultivating and making only wine,” Florian explains. The shift from subsistence farming to viticulture took place within a single generation. Florian drives home the starkness of the transition: “My father told me that, in the ‘80s, when he started to reduce yields in the vineyard by doing green harvest, his father (my grandfather) couldn’t believe it. My grandfather’s generation couldn’t handle seeing grapes on the ground — understandably after what they had gone through. So every year in July my grandfather went on holidays and told my father to cut the grapes during that week so he didn’t have to see that. Only after some years, when my father, among other winemakers, started to have success with his ‘new’ wines, did my grandfather and his generation started to understand it.” Untermoserhof has always been passed from father to son, but Georg and Florian, the fourth and fifth generations, work as a team, sharing responsibility for both the vineyards and cellar. Florian notes: “2018 was my second harvest at home. My father has the experience and I try to adapt little things with my ideas — but we decide everything together. “

Georg and Florian Ramoser

Georg developed his understanding of Alto Adige’s native varieties growing up among the vines at Untermoserhof and through work experiences at Alois Lageder and Cantina di Bolzano. Florian realized he wanted to be a winemaker, “already when I was a kid. Growing up, seeing your father and family work the vines the whole year and then harvest them is very special.” He went on to study in neighboring Trentino and work for Luciano Sandrone, in Barolo. “Wine is a big part of my life,” Florian explains, “because many friends of mine are wine producers, too. We travel a lot to other wine regions and we meet very often to taste blind or in someone’s cellar from barrel. Other than wine, I really like playing ice hockey and just being with friends, going out for dinner and travelling. At home, we really love Barolo and Barbaresco, and French wines, too, especially white and red Burgundy, but also syrah from the Côte du Rhône.”

Santa Magdelena/Bolzano

Although Alto Adige/Südtirol looks back on two millennia of winemaking, its recent history was dominated by coops and it is only now truly emerging as a region for thrilling discovery of small individual producers. Culturally, it’s a place of intersection. Sited at a critical transalpine crossing, the region was long an object of contest between Bavarian dukes and Habsburg sovereigns, only coming under Italian rule at the end of WWI. But the language, architecture, cuisine — and wines — retain an individualistic Tyrolean soul. Few places are as traditional and yet transformed by recent history: Bolzano’s strategic value as a transport hub attracted heavy aerial bombing during WWII. Aggressive post-war rebuilding then swelled the city, pushing it deep into the farmland and vineyards that had surrounded it for centuries. Climatically, despite its Alpine location and latitude, Bolzano sits at the base of a great, heat-trapping bowl where average summertime temperatures exceed those of Palermo. The Alps catch most of the clouds and rain, making Bolzano’s weather reliably dry and clear, with some 300 sunshine days per year.

Lagrein and schiava

The two red varieties most closely associated with Bolzano and its immediate surroundings, schiava and lagrein, love this steady warmth and grow best in the calcareous, gravelly soils that trap and retain heat to aid ripening. They retain their freshness thanks to the starkly cooler mountain air that descends from the mountains each night.

Everywhere it is grown, schiava (a.k.a. vernatsch, trollinger), a generous bearer, has suffered from overcropping, leading to its reputation for giving anemic wines. But careful producers like Georg and Florian have trained their focus on older vines, green harvests, and careful cellar work to control yields and elicit characteristic vibrancy and delicacy from the variety. St. Magdalener is the region’s traditional schiava-dominant blend that is deepened by the addition of a small percentage of lagrein. The “Classico” designation identifies wines from historic sites on the northeastern edge of Bolzano.

Lagrein is one of Italy’s oldest native grapes. Its history goes back a thousand years in Alto Adige/Südtirol and it is, deservedly, one of northern Italy’s most prized red varieties. However, it is finicky, susceptible to coulure and prone to uneven yields, which has limited its appeal to growers outside the region. Recent DNA profiling suggests lagrein is the offspring of teroldego and kin to pinot noir and syrah; it shares noticeable aroma, flavor, and pigmentation characteristics with each. Lagrein gives one of the most deeply colored wines in Italy due to its high concentration of anthocyanins. It is also famously tannic, requiring careful management through aging in wood. A more refined understanding of lagrein biotypes (thought to number around 100, though most growers focus on just two) along with better understanding of its vinification needs have helped winemakers like the Ramosers capture the variety’s potential to give gloriously multilayered and complex yet highly drinkable wines.

Vineyards and farming

“We really believe in our two main varieties, schiava and lagrein, and want to focus especially on them,” Florian says — in notable contrast to many producers in the area, who still work with international varieties that have been popular here since the Hapsburg era. “We try to produce wines that express their vineyard’s character, showing terroir, depth, juiciness, and good drinkability.” The winery is 320 meters [nearly 1,000 feet] above sea level and the vineyards range from 280 to 400 meters [840 to 1,200 feet] a.s.l., with lagrein in the lower vineyards and schiava on the higher, steeper slopes, where the soil is less fertile. The vineyards cultivated with schiava (for St. Magdalener) and lagrein are all within the Santa Magdalena zone, at the northeast border of Bolzano. The vineyards are tiny parcels, some scattered around the winery and others a couple hundred meters away.” Vines range in age from 40 to 60 years old, with 100% pergola training for schiava — traditional for this variety, with its impressively pendular clusters — and a mix of pergola and guyot for lagrein.

Soils here are well-draining glacial and alluvial sandy loam and decomposed porphyry gravel. Florian explains that “the primary rock — volcanic ‘Quarz-Porphyr’ of Bolzano — dates back 270 million years. The soils of Santa Magdalena particularly were formed by glacial drifts containing porphyry gravel as well as alluvial deposits that enriched the soil with stones from the more northern parts of Alto Adige.” He thinks the lighter soils of the Hueb result in smaller bunches and berries, so “wines from the soil tend to be deeper and have more structure and spiciness.” Florian is convinced that, for Santa Magdalena, “having high density of vines — 6,000 to 8,000 per hectare — is important. This leads to roots that go deeper into the soil for more mineral, more concentrated wines with more depth.”

“We have about 4-5 % of lagrein in our St. Magdalener [DOC rules allow up to 15%] which, in the old vineyards, was planted together with schiava in the same parcel. It’s harvested together and coferments. These are two varieties that ripen at the same time, so it works pretty well,” Florian notes. He believes the greatest challenges and advantages of the area are: “the steepness of some our vineyards, which makes work pretty time-intensive ( about 600-800 hours per hectare/year). It can be challenging to keep fungus under control. On the other side, we have lots of sun hours and we reach full ripeness every year, even in colder and wetter years.”

“Almost everything has to be done by hand in our vineyards,” Florian underscores. “Most of the vineyards have narrow terraces we can’t enter with any tractor, just with a small crawler vehicle. Strong selection already takes place in the vineyard.” He and Georg work “as naturally as we can,” he says, “looking always to improve soil characteristics, plant characteristics, and to try to adapt things for improvement.” This includes careful canopy management and monitoring the health of the grapes, as well as trials with cover crops. “We are farming almost organically — I say almost because we make one or two [conventional] treatments only if it is needed in the most dangerous moments. We haven’t use herbicides in many, many years.”

In the cellar

Florian says he and his father share a “pretty similar” approach to style. “I’m convinced to let the vineyard express itself in the wine, trying to not do too much in the cellar. We don’t want to cover the fruit of our wines with too much new oak or something.” He explains that his father, along with the rest of Italy, seemingly, experimented with barrique for a time: “But since a couple of years, we use bigger barrels and about 25%, down from 40%, new oak. This leads to maybe a little less concentration in the wines, but more elegance and freshness.” Vinification is, in Florian’s words, “pretty traditional”: destemming, selected yeasts, and stainless steel and large oak barrels for alcoholic fermentation and aging. “The thing I’m experimenting with a little bit right now is using whole bunches during fermentation for lagrein — it leads to more depth and more spiciness.”

For the St. Magdalena, fermentation takes place in stainless steel and large oak cask that is also used for lagrein. During fermentation, pump overs are done twice a day initially, then once daily toward the end. After 10-14 days, wines are racked and pressed. Afterward, half the wine goes through malo in large oak and half in stainless. The wines age for about seven months, before bottling in May or June.

For Lagrein, fermentation takes place in stainless, with pumpovers twice daily “until almost the end of fermentation, to softly extract tannin structure.” The wine is racked and pressed and put in 2,500L oak barrels for malo and eight months of elevage. Normally, one bottling takes place in May, another in June.

For Lagrein Riserva, fermentation is split between stainless and large oak. Pump overs are done twice daily for the oak batch and pigeage for the stainless steel lot for the first five to six days, then pump overs are done, with care taken to avoid overextraction. After 18-20 days, the wines are racked and pressed, and put into 500L oak barrels for malo and 10-12 months elevage. After a year, they are racked again into in 2,500L oak barrels for a few months before bottling.

“The desire to be organic for us is not to put on the label a stamp, but to live the vineyard as if it is your life.” — Massimo Duri

Giovanni and Massimo Duri, father and son, are the fourth and fifth generation to cultivate Antico Broilo’s 6 hectares in the tiny commune of Prepotto. “Traditions are for us the most beautiful things that can be handed down,” notes Massimo. “We made a conscious choice to cultivate only varieties that were already present on the estate, to keep our history in the vineyard.” For the Duris, this means old vines and massal selections of four native varieties that scarcely survived the 20th century: friulano, ribolla gialla, refosco dal peduncolo rosso, and the pride of Prepotto: schioppettino. Their careful preservation of the vines and the culture that surrounds them extends to organic farming, tightly controlled yields, hand harvests, and minimal cellar intervention—native yeasts, racking by gravity flow, little added SO2, brief skin maceration for the whites, long aging in wood for the reds. This quartet of native grapes speaks a distinct local dialect to which the Duris are intimately attuned. Their wines convey it with purity, beauty, and character.

Prepotto

The Colli Orientali are the easternmost hills of Friuli, a corner of far northeast Italy tucked between the broad plain of Friuli Grave and the rising hills of Slovenia, mid-way between the Julian Alps and the Adriatic Sea. The region is gifted not only with a verdant beauty and fascinating interplay of cultures, but also a constant and beneficial exchange between cooling air masses from the north and warming sea breezes from the south—mitigating humidity, tempering summer heat, and drying the vines in what is the rainiest part of Italy.

Soils throughout the Colli Orientali are known locally as ponca. The distinctive, alternating bands of sandstone and calcareous marls were pushed to the surface as part of the broader Alpine orogeny. The ponca is topped by fine clay carried downstream from the surrounding uplands. These soils are prized for the texture, concentration, and—thanks to their relatively high pH—acidity they give to the wines.

Prepotto itself is a tiny subzone of the Colli Orientali that Massimo describes as being “surrounded by sweet hills, narrow and long and running along the Judrio River,” a waterway that separates the Colli Orientali from Collio and Slovenia. “The hills following the path of the river channel a light breeze that daily manages to create a particularly interesting thermal excursion, especially for our schioppettino,” he explains.

Small, tradition-minded producers like the Duris have staked a claim for the unique expressions of their native grapes on terroir to which they are singularly adapted.

Ribolla gialla has been grown in eastern Friuli since at least the 13th century, but after phylloxera and the travails of the last century, wines made from this variety had dwindled to less than 1% of Friuli’s DOC production. The 1990s marked a turning point, though the grape still commands just 2% of Friuli’s vineyard land. As Gravner and Radikon have taught the world, the grape is particularly suited to maceration. The Duris’ favor skin contact, albeit brief, “to combine the appeal of acidity with the intriguing subtlety of the whistle-clean tannins,” as Massimo says.

Friulano also has a deep history in the region, as its name indicates, though genetic testing has revealed it to be identical to sauvignon vert a.k.a. sauvignonasse. Despite its thin skin, it is fairly resistant. The wines tend to be aromatically delicate, with fresh floral and almond notes, and are light in color and body. They, too, take well to the one to two days of maceration the Duris favor.

Refosco dal peduncolo rosso, the refosco “of the red stalk,” is the best known of the genetically diverse refosco group. It has also long been at home in Friuli. DNA profiling shows a kinship with the northern Italian red varieties teroldego, lagrein, corvina, and corvinella. It thrives in poor, calcareous-clay soils and on hillsides, ripening late and characterized by intensely dark- blue berries with thin but resistant skins. The wines feature a strong tannic structure, with a characteristic northern profile of dried cherries, herbs, almonds, and violets.

Schioppettino takes its name from the Italian word for “crackling,” in reference either to the variety’s crunchy berries or bottle refermentation that made the wines slightly sparkling in the past. It, too, has been cultivated in Friuli since the 13th century, when, according to Italian wine scholar Ian D’Agata, “the amphitheater of Albana-Prepotto was almost completely under vine and schioppettino represented about 75 percent of the vines planted there.” Today, the grape is at home almost exclusively in Prepotto, where it thrives in alluvial soils with optimal ventilation amid warm days and cold nights. However, this variety is susceptible to extreme millerandage and flowering problems, especially in rainy, cold springs, making it is an unreliable yielder. For a time, planting schioppettino was banned outright, under penalty of fine from local authorities. The grape became so obscure, it disappeared from the official Italian grape registry. But in the ‘70s, local advocates mounted an impressive effort to effect the grape’s revival. It took decades, but in 2008, the wine obtained its own designation Schioppettino di Prepotto. Still, the quantity of schioppettino the 20-odd small growers who work with the grape can produce remains tiny. The Duris’ wines give us a rare opportunity to experience a wine of spirited freshness, redolent of violets, black fruit, earth, and a syrah-like pepper note thanks to high levels of rotundone. Fine-grained tannins and lively acidity lend structure and finesse and the wines age remarkably well, gaining savory elements and silky complexity with time.

Winemaker

Massimo, 36, is a trained agricultural expert. Yet he credits his parents and grandparents with “making me love this tiring job.” He explains, “when you work as a family, you can’t do everything yourself. I always found it nice to share our passions and tastings year after year. My father is and will be a very important reference for me. He tells me to see a wine in perspective, drink it now and imagine it in ten years, that’s the secret. I also think that my father loved from a young age this work that makes you sense aromas and see horizons that only can be seen in nature. The most beautiful memories are those of flowering, when the whole vineyard smells of honey or with the reaching of autumn when the leaves turn colors and the landscapes become paintings.”

Vineyards and farming

“Decades ago,” Massimo contextualizes, “wine was seen as a food used both for meals and for calories in laborious hours of work in the country. So the vineyards, in my opinion, were exploited more for the quantity of grapes they gave because people needed a light and unstructured wine.”

By the early 1990s, things had obviously changed. “We immediately understood the way to go thanks to my father, who started looking for qualitative techniques—selection of the bunches, cleaning of the vines, selection of the shoots.” Today, this means taking massal selections from centenarian vines “to keep our history in the vineyard.”

“We regard our estate as a garden,” notes Massimo. “Our 6 hectares are all in a single body and mainly consist of clay with sand, capable of drying the soil quite well in case of long rainy periods. Our valley floor is very rich in organic substances and fine earth, typical of this land. We focus on vine quality, monitoring bunch loads per vine—after reducing yields by as much as half, to 40-50 hl/ha. We never force the productivity of our vines, which means they are able to adjust to dry or wet periods, even to drought.” After many years of growing fruit on the traditional cappuccina (Friulian double-arched cane), the Duris switched to Guyot, and added cover crops to further constrict yields.

“Our basic principles are to preserve the typicity of the vine, avoiding chemical fertilization, and use curative products allowed by organics,” Massimo asserts. Despite the challenges of farming in Friuli’s rainy climate, the Duris are intent on minimizing the application of copper sulfates and are always experimenting with new plant protection products, such as a current investigation into one based on seaweed. “The desire to be organic, for us, is not to put on the label a stamp, but to be in harmony with the lunar paths, to live the vineyard as if it is your life,” Massimo says. “It is very important to know where we are, how the soil is made, what vines there are, and above all to know ourselves. We have always employed eco-friendly farming methods and act in full respect of the ecosystem. As proof of the healthfulness and eco-friendliness of our approach, we can point to the presence in our plots of small birds that choose our vines as their nesting site. We tend the vines and thin the canopy regularly, often spotting eggs or newly opened shells, a wonderful testimony to the estate’s respect for nature and proof of its sustainability.”

In the cellar

After hand harvesting and bringing the grapes to the crush pad in small trays to avoid damage, they are gently pressed and spontaneously fermented. “It’s normal for us to use native yeasts,” notes Massimo. “My grandfather did it, my father did it. When you use yeasts that are born in nature or on the grapes you realize the commitment that nature already makes to create them, so I commit myself to express a traditional wine with those yeasts. We use low quantities of SO2, added only at bottling and depending on the vintage, because it is important for long aging in bottle.”

Ribolla gialla and friulano are skin macerated for one to two days, go through malo, are raised 90% in stainless steel, 10% barrique for eight to nine months on the fine lees, and another three after bottling.

Schioppettino, Massimo relates, “is harvested only in the early hours of the morning so as to not lose aroma and spice. Maceration is in stainless, and aging in barrique (10% new) for 24 months.” Refosco dal peduncolo rosso is harvested around mid-September as berry maturity is essential to avoid vegetal notes in the wine. Maceration here is also in stainless for 20 days, with 24 months elevage in barrique (again 10% new).

The Duris are committed to regenerative practices wherever possible in the cellar: all racking is by gravity flow, waste water is repurposed, lighter-weight bottles and responsibly manufactured corks are favored.

“Nobody will give you ‘the recipe.’ But you can learn a small detail every day.” — Mitja Sirk

A family legendary in Friulian hospitality. A young son reevaluating Friuli’s vinous heritage through the lens of experience with Gravner, Conterno, Dujac, and Roulot. A single traditional variety. A fresh, distinctive voice. That voice, that son is Mitja Sirk. His wine story opens with an extraordinary chapter. At age 11, with Josko Gravner’s encouragement, Mitja made his first wine. Over seven vintages, under the master’s eye, he refined his understanding of Friuli’s past and potential. With time, his focus has narrowed. He now works with one grape — friulano — in a single style. He seeks out old vines, ponca soils, traditional trellising, clean farming. In the cellar, he has moved away from extended skin contact and amphora, towards stainless steel, long lees aging, and batonnage, to make a wine that is, in his words, “very clear and direct.”

The Sirks of La Subida

The Sirk family, Josko and Loredana, and their grown children, are originally from Slovenia, but have been at home over the Italian border in Cormons for more than half a century. “My father ran the estate until the 1974 vintage,” Mitja explains, “but he decided to move his attention from farming to the [now Michelin-starred] restaurant and the [now world-renowned] hotel, La Subida. For 30 years, the vineyards that we own were worked by our cousins. Finally, in 2003, we took them back for vinegar and wine production. Vinegar production is my father’s big passion,” notes Mitja. “I restarted the wine production in 2016, as a project based on working exclusively with friulano, the typical variety of our region.”

Mitja Sirk

“I realized I wanted to be a winemaker when I was 11 years old, visiting a local winegrower called Josko Gravner,” Mitja relates. “He took me under his arm and said that he would give me one of his clay amphorae. He did! And one month later he brought some grapes. My first wine was made.” Mitja went on to study at the local viticulture and enology high school, though he was discouraged by the “quite retro” approaches he saw there. He resolved to travel and learn directly from winemakers he admires throughout Europe. “I think that a smart and interested wine producer or wine lover wants to learn from as many other wine people as possible,” he says. “Each visit, each dinner, each talk can be helpful to discovering a new way of doing something. Tasting regularly with my best friend Kristian Keber, Edi Keber’s son, helped me a lot to understand better Friulano and its nuances. I staged at Dujac in 2013 and Conterno in 2014, as well as Isole e Olena in 2011 and Roulot in 2018. Nobody will give you ‘the recipe.’ But you can learn a small detail every day. The cleanness that Conterno wants in his cellar even during harvest is incredible. The experience and confidence that Jean Marc Roulot has with his vineyards, unbelievable. The simplicity and history of Dujac gives you the feeling, even if you are there just for a couple of weeks for a stage, that you can make that history as well.”

Cormons in Collio

The town of Cormons is just a mile from the Slovenian border, in the horseshoe-shaped region of eastern Friuli referred to simply as Collio (“hills”). It is a place defined by confluences. Midway between the Julian Alps and the Adriatic Sea, it is, Mitja notes, “a classic Mediterranean region, warm in summer, but, as a classic Alpine area, cold and wet in winter” — ideal conditions for the thin-skinned but early-ripening friulano. Culturally, Collio has long been an area of overlap for Italian, Austrian, and Slavic influences. “The best part of Friulian wine is the diversity,” Mitja told Levi Dalton in a 2016 interview. “I think history makes the decision for us. We were first under the Venetians, so we were selling the wines there. The best period was the Austrian Empire because we were the warmest for vines. Then the ‘60s and ‘70s brought us to increase production of international varieties.”

The successive dominance of empires and republics here has left the region with a multifaceted identity and a miscellany of varieties. Cormons remained under Habsburg rule until the end of WWI, leading to a preponderance of “noble” varieties, including sauvignon vert, which became tocai friuliano in its adopted Friulian homeland. (It has since been shorn of its tocai prefix by legal action from the Hungarians). The grape is traditional and widely planted in Collio (though recently in decline), long prized for its aromatic delicacy pronounced mineral, floral, and sweet almond notes, with a characteristic catch of bitterness at the finish.

WWII took a heavy toll on Collio. In the postwar period, Friuli rebuilt its economy based largely on wine, but it did not emerge as a source of notable wines until the late 1960s. Since that time, the region’s winemaking identity has undulated nearly as much as its history and landscape. “Friulian” has, in turn, meant “Germanic” (clean, crisp), “Burgundian” (oak influenced), and “Georgian” or “radical traditionalist” (skin contact, amphora). Now, Mitja is putting his own stamp on a style we might cautiously term “purist” (a move toward native and traditional grapes, native yeasts, minimal skin contact, long lees aging, stainless steel, temperature control.) “In Friuli, ‘traditional’ can give many different visions,” Mitja notes.

Vineyards and farming

The soil is relatively consistent throughout Collio. “It is a type we call ponca in Italian and opoka in Slovenian,” Mitja explains. “It looks like a series of compressed stones, made of hard, compacted sandstone and marl. On the surface this stone breaks very easily. This broken stone will mix with the organic matter and the clay portion to create a very good growing environment.” Ponca brings pronounced texture, concentration, and extract to friulano, a variety that tends to delicacy. “We try to find old vineyards for the single vineyard parcels. That is not easy. Our oldest was planted in the 1960s. I’m trellising the vines in the local cappuccino or doppio capovolto [double arch cane] style, I’m picking the grapes at physiological ripeness.” Mitja declares his farming philosophy to be “not using pesticides and herbicides as a simple and basic rule.”

In the cellar

Despite Mitja’s early start with Gravner, “I’m not doing skin contact,” he says flatly. “Josko helped me for the first seven vintages, making orange wine. I was young, but super excited. I think he showed me that wine can be made by a young child without any technology, knowledge. Just a couple of simple rules. Now I’m controlling the temperature during the fermentation, using steel vats; in the future, there will be some cement and oak barrels as well.” Mitja’s style is, in his words, “to be very clear and direct. When I started in 2016, I began by making all the wines in a very classic way. I use gentle pressing, with a cold soak overnight. Fermentation is started in stainless steel. We are moving away from selected yeasts. At the end of fermentation, we try to keep the wine on the fine lees and we work with a light batonnage — but working in steel I have to be careful about reduction [to which friulano is especially prone]. Filtration is done once, at bottling.” These early vintages show structure, elegance, and remarkable focus.

“Martissima is meant to be a provocation.” — Marta Venica

The name comes from jokes among Marta Venica’s friends. They added the “issima” to emphasize what she winkingly calls her “superlatively good, but above all, bad sides.” Marta launched her project in 2019 with the idea of giving fresh expression to practices rooted in tradition: organic farming carried out by hand and horse, and a focus on Collio’s native and traditional grapes vinified for freshness, texture, and verve. She makes just two wines. Each is a lyrical, free verse poem to nature, spirit, and place.

Marta Venica

“I have breathed the world of wine since I was a child. My dad” — Giorgio Venica, of the benchmark Venica & Venica estate in Dolegna — “has always been involved in the production of wine in the family business. At 18, I started to support him during harvest. My studies at university and the experiences I’ve had around the world have only made me more passionate,” says Marta.

After earning a degree in viticulture and enology from the university at Udine, which included a year at Geisenheim, Marta plunged into a range of wine experiences. In addition to having helped with harvest at the family domain since 2013, she has also worked at wineries “where the picking starts when the home harvest is over,” as she puts it. In 2014, it was Ceretto in Castiglione Falletto; in 2015, it was Dönnhoff in the Nahe, “the most amazing experience to understand what a meticulous selection of the grapes means;” in 2016, at Pierre Peters in the Côte de Blancs “for the real meaning of terroir;” in 2017, with Elisabetta Foradori in Trentino for a high-level introduction to biodynamics.

But in 2018, her life was transformed by a stage at the pioneering Patagonian biodynamic winery, Bodega Chacra. “The energy that allowed me to start my project surely comes from here. On the flight home, I decided I wanted to express my creativity through what I like to do most: being in contact with nature and spending the days in my corner of paradise.”

Collio

That corner is the small, hilly part of easternmost Friuli known simply as Collio (“hills”). It’s a place of complex confluences. Perched between Italy and Slovenia, the Alps and the Adriatic, its diverse geology, topography, cultures, and traditions all mark the region’s wines. As Marta puts it: “Collio represents the geographical limit between the Mediterranean and central Europe in climate, tastes, agriculture, and way of life.”

Despite Collio’s small size, it is hard to speak of a single identity for such a mosaic. Marta, together with her like-minded partner (and fellow Schatzi!) Mitja Sirk, is putting her own stamp on a style we might term “purist.” It’s a shift toward native and traditional grapes, responsive, organic farming, spontaneous ferments, minimal skin contact, and long lees aging, all yielding wines of vitality and character.

Vineyards and Farming

Marta now owns and works just one vineyard. It’s a small, low-slung, southeast-facing plot on ponca, a sedimentary rock of layered sandstone and marl. The plot is divided into four small parcels completely surrounded by forest. It’s planted to a mix of malvasia, ribolla gialla and friulano “planted randomly in the 70s,” as Marta notes, among vines of merlot and refosco. Farming organically, Marta’s emphasis is on handwork — and horsework. She relies on her pair of Arabians for the high-quality compost she uses to make her own organic fertilizer. Her aim is to stimulate the development of native microorganisms who, in her words, “permit a soil full of life.” Her hope is to incorporate more animals into the vineyards soon, to restore the natural balance that human influence has distorted.

Cellar

In the cellar, Marta’s objective is “to intervene as little as possible and maintain the integrity of the grapes.” For her Collio Bianco, a blend of equal percentages of malvasia, ribolla gialla, and friulano, the grapes are picked into boxes, pressed directly, and co-fermented. Fermentation starts spontaneously, two-thirds in stainless steel and one-third in barrique. If malolactic happens, she lets it. When fermentation finishes, she racks into tank, adds a judicious measure of SO2, and does battonage once a week for a month. For her Collio Rosso, which is mainly merlot with the animating addition of refosco, she relies on whole cluster fermentation in stainless steel for ten days. Fermentation finishes in barrique, the wine ages first in barrique, then in tank for one year. The wines then rest till bottling in May and enjoy one year of aging before release.

“A piece of land on a gentle slope, completely invaded by brambles and weeds, has become the catalyst for the energies of friends eager to return to the ancient traditions of the native land.” — Cesare Avenia

The story of Il Verro is rooted in a friendship among five teenagers who met in the 1960s. Some 40 years later, they reconvened where they had spent their childhoods — in Alto Casertano. The allure was understandable: unspoiled verdure and forested mountains, memories and connection. It was this landscape, this context that inspired Cesare Avenia and his friends to call into life a haven of history and biodiversity. Amid 14 hectares of olive, walnut, and cherry trees are 4 hectares reserved for vines — all wildly rare grapes indigenous to this remote reach of northern Campania. “Our mission,” says Cesare, “is to enhance our viticultural heritage and make wines that follow the traditions linked to the territory.” Volcanic soils and relative poverty have discouraged both phylloxera and replanting, gifting the region with a wealth of native grapes — among them casavecchia, pallagrello nero and bianco, and the ultra-rare coda di pecora. Respect for these historic varieties and a desire to understand them as they have adapted to the singular climate and terroir of Alto Casertano compel Cesare and his team to organic farming practices and a purist cellar style. The freshness, intensity, and directness of Il Verro’s wines speak to the primacy of its mission, its varieties, its place.

Alto Casertano

Alto Casertano falls between Campania’s better known regions. It has no DOC. Its terrain remains quite uncharted for viticulture. Within the embrace of forested peaks and three natural parks, the Volturno river courses to the Gulf of Gaeta. Wild boar (in local dialect ‘u verru, hence Il Verro) have had the run of the place since at least the time of the Bourbons. “The variety of the landscape and the healthy, ‘sparkling’ climate make Alto Casertano an unspoiled place of environmental, natural, and archaeological interest. Discovering this land means discovering ancient origins and a priceless wealth of history, folklore, and charm,” Cesare avows.

The region’s relative obscurity is sheltering. “It is rich in rare, autochthonous vines and is one of the richest in biodiversity in Italy,” explains Cesare. “At Il Verro, we have rediscovered coda di pecora (in English, tail of the sheep), which risked extinction.” Campania is a trove of native grapes, with many still uncatalogued or lost in a sea of synonyms. Even in this context, coda di pecora stands out as among the most obscure. Il Verro is the only producer in the world to grow and bottle it as a monovarietal wine.

Cesare Avenia and Vincenzo Mercurio

Decades ago, Cesare left Caserta for a career in telecommunications that took him around the globe and to many great wine regions. In 2003, he began to reexamine the world he had left behind. Wines of his region “did not, at the time, adequately enhance the richness of the wine sector,” he explains, “When I chose to come back to my origins, it was important to me that the grapes come from fully owned and native vineyards, characterized by rich lava soils, facing southeast and southwest, where there are significant temperature shifts between day and night. The development of my region’s vinous patrimony and the production of fine organic wines that follow the traditions linked to my home terroir is my philosophy.”

Today, Cesare leads Il Verro. He recognized early on that his lack of agricultural training would require him to employ an expert, preferably one steeped in local culture and traditions. He found this, and more, in a consultant named Vincenzo Mercurio. Vincenzo, says Cesare, “works with a method that respects the grape variety, the territory, and the people who animate it. Committed to the historical recovery of many endangered vines, he believes that Italy has an ampelographic heritage that still holds many opportunities. As a strong supporter of the organic way of life, he participates in round tables and seminars aimed at providing practical tools to live organics as a philosophy of life, not as a sterile operational protocol. His motto: ‘Wine is the history of the land, of vines, and of men.’”

Vineyards, farming, and varieties

Since 2013, farming at Il Verro is strictly organic. The vineyards, on the gentle slopes of Monte Maggiore, have variable exposures from southeast to southwest, at an average altitude is 300 meters [nearly 1,000] above sea level. Diurnal shifts are significant. All vines are 15 years old and pruning is both guyot and a traditional form of the area, known as garland. Planting density is 4,000 vines per hectare. Cesare describes his soil types as “clay/sandstone-clay, rich in clay fragments, strips of varicolored clays, frequent and, sometimes voluminous, exotic carbonate.”

All of his vines are native or nursery clones from neighboring territories. “The benefits of working with ancient autochthonous vines are that these vines are in harmony with the ecosystem and they retain distinct characters that cannot be found elsewhere.”

Pallagrello bianco and nero are two in a cadre of native Italian grapes abandoned in the last century, increasingly adored in the present. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the local ruling family treasured these varieties, earning them a spot in the royal vineyards, as Ian D’Agata points out in his Native Wine Grapes of Italy. But, the author notes, by the late 20th century, no one in Italy was producing a monovarietal pallagrello wine. Cesare explains that forces of powdery mildew and phylloxera “decreed a fast disappearance and substantial oblivion despite the undoubted qualities of these grapes.” Now he and a small handful of other producers are committed to their revival. Pallagrello bianco has always been most at home in northern Campania, where the climate suits its high-acid profile and tempers its inclination to rapid sugar accumulation. Pallagrello nero was once grown throughout Campania but has since retreated to Caserta, where it can best develop its soft tannins and characteristic notes of black fruit, black pepper, and herbs.

Casavecchia’s story traces a similar arc of near loss and rediscovery. Little is known about the grape’s heritage, which, Cesare notes, is the very reason it is so fascinating to pursue. “What is clear,” D’Agata proclaims, “is that it has found its protectors in Caserta. Despite its poor productivity and low vigor, Casavecchia is here to stay.” Cesare, of course, sees the natural advantage in low yields. The Lautonis bottling is raised in stainless steel, while the Montemaggiore sees 15 to 18 months in tonneau. The wines are supple and delicate with a marked herbaceousness.

Cesare cheekily labels his coda di pecora as Sheep. “Its name derives from the shape of the cluster, which resembles the tail of a sheep,” he notes. “After many years of confusion between coda di pecora and coda di volpe (tail of the fox), in 2005 we performed a DNA examination that certified the grape’s individuality and initiated the procedure for registration among the vines officially recognized by the Italian authorities. Precisely because this procedure has not been completed, the name of the vine may not appear on the label. Hence, Sheep.” The wines are savory and mineral, with intense aromas and flavors of ripe white peach, leading to a clean, pleasingly bitter finish.

In the cellar

“The style of my cellar is based on purity and naturalness,” says Cesare. “We like to experiment and adjust the vinification technique to simplicity and respect for the grapes.” Following hand harvest into small, protective baskets, the grapes follow a similar course in the cellar: destemming and gentle pressing followed by fermentation in temperature-controlled 10,000L stainless steel tanks.

Sheep was the first Il Verro wine to be spontaneously fermented, starting in 2018 (Cesare says experiments with native yeasts for other white varieties are ongoing). Beyond this, the wine sees the same cellar treatment as the other whites.

Casavecchia Lautonis is vinified just as Sheep and Pallagrello Bianco are, but then, after racking off the gross lees, it waits for the completion of malolactic fermentation in steel, and then another racking is done. The wine is raised in steel tanks until April or May, when it emerges with intense and lively notes of ripe red fruit, berries, and violets, structured but supple.

Pallagrello Bianco is straw-yellow, with a nose of melon, almond, broom flowers, and mint. On the palate, it is fresh and long. Pallagrello nero is vinified in the same fashion as Casavecchia-Lautonis, but gives an altogether darker, more savory wine with an alluring nose of fresh fruit, almond, and broom flowers and soft, integrated tannins. The essence of Il Verro’s wines are “flavor, minerality, and persistence,” says Cesare. “All my wines have a high aging potential, the whites at five to eight years and the reds at 10-15.” Together, they offer an insight into the terroir and tradition of a place very few have yet discovered.

“The idea from the first day was to work the vines and make the wine just like Grandpa did: with minimum intervention and zero chemistry.” — Giuseppe Scirto

Cool climate wines from a Mediterranean island on the latitude of Tunisia? Yes. Welcome to Etna. Here, on the northern slopes of Sicily’s epic volcano, Giuseppe Scirto and Valeria Franco tend a true polyculture: 4 hectares of vines and 1 hectare of olive, nut, and lemon trees, all at 600-1,000 meters [1,900-3,200 feet] above sea level. Carricante, nerello mascalese, and nerello cappuccio planted between 1900 and 1930 in black volcanic sand and pumice soils work a slow magic. The vines can only extract nutrients over the most gradual timeframe, extending the life of the vine and concentrating a range of savory, mineral elements in the grapes and the wines. Giuseppe and Valeria’s personal history with the land coupled with the tiny, two-person scale of their farming give them a visceral grasp of grape and terroir. Working organically in the vineyards and with radical minimalism in the cellar, they bring forth wild and lively wines. Even as the wines flirt with funkiness, this is never allowed to obscure terroir expression. Giuseppe and Valeria have no formal wine schooling, but are guided by their own intuition, the teachings of Giuseppe’s grandfather, and a primal respect for their untamable terroir. The excitement surrounding Etna wines is in part the thrill of discovering a lost world, with so much of its territory and tradition intact. But for Giuseppe and Valeria, there is no rush to rediscover. They’ve been connected to this place all along.

Origins

The vineyards Giuseppe and Valeria work today belonged to Giuseppe’s grandparents, who produced bulk wine, “as everybody was doing on Etna until about 20 years ago,” Giuseppe points out. When Giuseppe’s grandfather, Don Pippinu, died in 2005, it was at a time when small vineyard owners on Etna had begun to sell off their holdings. “Ours were particularly requested because they are in a highly valued area. But I was very close to the vineyards because from a young age, I spent all my summers there together with my grandfather. Walking in those vineyards, I revived a memory. I could never sell to others the sacrifices of my grandfather, also because no price could repay a bond like that between me and him.”

“In 2009, we started to work the vineyards. 2010 was our first vintage. The idea from the first day was to work the vines and make the wine just like Grandpa did: with minimum intervention and zero chemistry. We did not study enology. Perhaps our own ‘ignorance’ initially allowed us to make this choice. Having a great passion, being connected with many other producers, and being self-educated has helped us to know more deeply the vines and the wine. In the vineyard and in the cellar, we work, just the two of us.”

Giuseppe Scirto and Valeria Franco

“There was not a precise moment,” Giuseppe says of his realization that he wanted to become a winemaker. “I grew up with this passion, but only became aware of it a few years after the loss of my great master, Grandpa.” Giuseppe and Valeria were entwined in wine and life on the mountain before they met. Beyond his childhood in the vines, Giuseppe had also worked at Calabretta, a pillar of traditionalist Etna winemaking, where the wines evoke the principled old school of Barolo. Valeria brings to bear her heritage as one in a long line of farmers and family winemakers.

Northern Etna

“We produce wine in an area that is so different from the rest of Sicily, it is considered an island on the island,” Giuseppe notes. Etna is a stratovolcano, built layer upon layer from the seafloor to its present height of 3,350 meters (nearly 11,000 feet) above sea level over the past half-million or so years. It is one of the world’s most active volcanoes, not just at its main crater, but also in and around myriad vents and fissures that continually conduct lava flows of varying size and intensity. This has surfaced the mountain with an array of extrusive igneous rock and soil types — critically, all comparatively young and unweathered. As John Szabo writes in Volcanic Wines, even “the same volcano can erupt different lavas at different times due to changing composition in the magma below.” This means critical differences in proportions of silica, iron, magnesium, potassium, calcium, and sodium as well as rock structure from eruption to eruption, flow to flow.

In volcanic terrain, there appears to be an inverse relationship between the ages of the soil and the vine: the younger the soils are, the older the vines can become. This is due to the balanced presence, but extremely limited availability, of macro and micro nutrients in the lava rock as well as the hostile environment it creates for pests like phylloxera. Gnarled, slow-growing, centenarian vines are an Etna hallmark. Scirto’s are prime examples of the silent power they exude.

History and culture — here speaking just of the past century, not to mention millennia of habitation and wine cultivation — also distinguish wines made on Etna today. Szabo points out that countless Etna vineyards were either abandoned or cultivated solely for local consumption, lifting commercial pressures to replace low-yielding or unfashionable vines with other material. Moreover, as Italian wine scholar Ian D’Agata writes, “the fierce attachment that Sicilians have to their roots and traditions means that any input coming … from grandparents and other family members would be heeded more here than in other regions.” This keeps roots deep and generational connections vibrant.

As Giuseppe sees it, “the advantage of our region is definitely of being in the south of Italy, but at the same time of being in the mountains. This greatly helps the thermal excursions. Moreover, our volcanic soils have the particularity of good drainage. Humidity is very low, so very few diseases proliferate, even though the rate of rainfall here is higher than the rest of Sicily. Our vineyards, even if close to each other, are quite different, as they are formed by stratifications of different lava flows, so we have some vineyards with deeper soils and others with more pumice.”

The north slope of Etna is somewhat cooler than the vineyards that wrap around all but the truly inhospitable west side of the volcano. But here, altitude is more significant than exposure. It impacts not only temperatures (lower) and rainfall (wetter), but, as Giuseppe notes, soil depth, too. Soils are deepest where lava flows have been most frequent and abundant, that is, closer to the top of the volcano.

Vineyards and farming

Sicily’s native varieties are intrinsic to the island’s self-expression. And few grapes are better adapted to the austerity and intensity of Etna than carricante, nerello mascalese, and nerello cappuccio — at Scirto, all alberello trained, per local custom. Giuseppe and Valeria have a half hectare of carricante, Etna’s principal white grape, aptly described by D’Agata as “a hermit that loves mountainous altitudes.” It is perfectly at home in the higher climes of Etna — and virtually nowhere else in Italy or the world. Low yields from the old vines at Scirto bring intense stoniness and salinity to the wines, with marked acidity, tempered by letting the wines go through malo, as Giuseppe and Valeria do. Carricante is sometimes compared to dry riesling, especially in regard to the flinty register expressed by older bottlings.

Nerello mascalese is an almost one-to-one match with nebbiolo in its high acids and tannins, low pigmenting anthocyanins, late ripening, terroir articulation, and ability to age into grace and nuance. It is thought to be a natural crossing of sangiovese and mantonico bianco, a Calabrian white variety marked by high tannin and acidity levels. Nerello mascalese is vigorous, but responds sensitively to terroir, planting density, and training method. It tends to give wines of savory mineral character underscoring red cherry and herbal notes. Nerello cappuccio plays the perfect counterpart to mascalese. The complementarity of the two starts in the vineyard, with staggered bud break and harvest times. Cappuccio is far less widely planted, more muted in its terroir expressiveness, lower in tannin and darker in color, easily explaining its selection as the traditional blending partner for mascalese.

Working such a small area, Giusseppe and Valeria are acutely attuned to the ways in which the intersection of altitude and soil type affect their trio of varieties. “For example,” Giusseppe says, “our Don Pippinu comes from a vineyard at 700 meters above sea level with very deep soil and pumice, giving wines that are more structured and longer aging. A ‘ Culonna grows in our primary vineyard, 100 meters lower, in Contrada Feudo di Mezzo, where the ground is very rich in pumice, rather than rocks. And our white is a blend of grapes that we collect from all our vineyards.”

In the cellar

“Our philosophy is quite simple: minimum intervention! We believe that if you work well in the vineyard and you farm healthy grapes, there is very little to do in cellar. Our wines are all born from spontaneous fermentations in stainless. We decide the days of maceration according to the vintage (we have no protocols), all the wines do malolactic fermentation, and we only bottle when we are ready. All our choices depend on the sensations we feel every time we taste from the tanks. Even the decision of whether or not to add sulphites is a very sensitive one. In cases where we decide to add, it is always under 40 mg/l.”

The carricante see three to five days of maceration and zero added SO2. It is raised for 10 to 12 months in stainless steel before bottling, accentuating alluring and incisive aromas of orange peel and pink peppercorn. A’Culonna Etna Rosso DOC is named for a volcanic rock column that serves as a local meeting place in Passopisciaro, where Giuseppe’s grandfather used to take him as a boy. When visitors came to town looking for wine, they’d see Giuseppe’s grandfather sitting by the column and ask him where they could buy wine. His grandfather was only too happy to oblige and led the visitors to his own cantina. Scirto’s Rosso honors this memory. Giuseppe and Valeria make the wine at Calabretta, where they allow it an extended maceration (10- to 45-day, depending on the vintage), spontaneous fermentation in stainless steel, and elevage in 2000L Slovenian oak botti for 18 months and in bottle for a further six months before release.

“Compared to previous generations, the differences between my generation and the previous one relate mainly to the way of working in the cellar,” Giuseppe asserts. “In fact, we continue to work in the vineyard as our grandparents did, without using chemistry and most of the work we do manually. In the cellar, we do longer skin contact and aging. We use mainly steel and do a lot of cleaning because that is one of the things we care more about!”

“I feel an indissoluble connection with this place.” — Giovanni Messina