“That things would be hard for us was clear. What we hadn’t expected was that they would also bring so much joy.” — Angelina and Kilian Franzen

Angelina and Kilian Franzen’s story is every bit as moving as their wines. It begins in the Mosel’s Bremmer Calmont. After millennia of cultivation, these sheer vertical vineyards — among the world’s steepest — had, by the 1980s, been abandoned. One wine grower embraced the daunting prospect of recultivation: Ulrich Franzen. “His vision was to bring the Mosel Terraces, especially the Bremmer Calmont, back to where it once was: at the top of German wines,” explains his son, Kilian. Tragically, in the middle of this heroic project, Ulrich lost his life. Kilian and his future wife, Angelina, then still students, returned home to take over the estate. Today, the Franzens have 5 hectares in the Calmont and holdings in the venerated Neefer Frauenberg and Kloster Stuben vineyards nearby. The focus is, naturally, riesling, with small plantings of elbling and pinot varieties. Vines are up to 90 years old, their roots driven into the terraced slate, giving immense concentration to the wines. Perhaps because so much has been forced in the vineyards and in the Franzens’ young lives, nothing is in the cellar. Fermentations are spontaneous, some taking nearly two years to complete. The wines go through malo and GGs are bottled late. All this accounts for wines that are as much about texture, herbaceousness, and salinity as they are fruit. They display remarkable freshness and animation as well as power and echoing length. Because so little wine is made from the Calmont, the wines have largely remained a secret, even among riesling connoisseurs. Through pure dedication and heart, the Franzens have made it the source for some of the most arresting wines in all the Mosel.

History

Wine growing in the Mosel valley dates to around 280 AD, when Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius Probus lifted the ban on cultivation outside what is now Italy, and cultivation spread throughout the Rhine and the Mosel. The Mosel Terraces form a unique landscape, very different from that of the more famous Middle Mosel. Topography and soils are paramount here. The microclimate is warmer, the vineyards more vertiginous, and viticulture more difficult here. The hand-built terraces that give the region its name have always been essential to enabling vines to grow in the cold macroclimate and steep terrain.

Even the Romans called the Bremmer Calmont mons calidus, hot mountain. By the 19th century, the Calmont’s suitability to riesling had become obvious: the entire mountainside was planted to riesling. The upper portion, known as the Fachkaul, was awarded the highest classification on tax maps of the time. Yet after WWII, lack of manpower and will to meet the intensive demands of the vineyards led to abandonment of these parcels, one by one. By the 1980s, the mountain was covered in roses and wild vines; only the parcels along the road and river remained under cultivation.

The Franzen family has been rooted in Bremm for centuries. Kilian’s grandparents had parcels in the Calmont. Kilian says it was always the dream of his father, Ulrich, to have productive vines up there again. “When my father took over operations from my grandparents in the early ‘80s, he changed the orientation of the estate and put the emphasis on the production of dry, lower-acid wines. Beyond that, the preservation of the steep sites was dearest to his heart.” In 1999, Ulrich resolved to buy all the contiguous Calmont plots he could. Napoleonic law had long since splintered the vineyards into tiny parcels, all with different owners. The only way to find out who owned what was to comb through town records. It took Ulrich three years to track down 112 different owners — from Australia to China to the U.S. — and purchase their plots. This enormous effort yielded a glorious prize: the steepest parcels, united in a magnificent, south-facing amphitheater in the very heart of the Calmont.

Painstakingly, Ulrich and a small team cleared and replanted the vineyards, all by hand. Within three years, they had anchored nearly 8,000 riesling vines in the obstinate slopes. The only concession to mechanization was the installation and operation of vineyard monorail lines — 500 meters of track ascending from the Mosel’s edge to the top of the Fachkaul.

This work “was my father’s life’s dream,” Kilian recalls. But before it could be fully realized, a tractor accident claimed Ulrich’s life in 2010. “Completely overwhelmed after the death of my father,” Kilian recounts, “Angelina and I took over the winery from my parents. We were in the middle of our studies and would have loved to travel after finishing. Instead, we came directly from Geisenheim to Bremm.” But the last thing you’ll hear from Kilian and Angelina are complaints: “Even though the maintenance of the steepest vineyards in Europe is one of the most physically demanding and intensive tasks we have, the preservation of this cultural landscape and continuation of hundreds of years of tradition fills us with pride and motivation every day. We tumbled into the adventure of our lives and know to treasure every moment of it.”

Winemakers

Angelina and Kilian were childhood sweethearts who went on to be classmates at Geisenheim, a winemaking team, husband and wife, and now parents to a young daughter who, in Kilian’s words, “is our life.”

Angelina is from Bullay, two villages downriver from Bremm, and her connection with winemaking runs just as deep as Kilian’s: “My family has also been involved in viticulture for many generations,” she explains. “My father has a winery a few miles away. My father’s cousin is Rita Busch, the wife of Clemens. It was many years after I decided to become a winemaker that I realized what an important role Clemens and Rita Busch play in German viticulture. But it was my parents and brother who shaped my path. My father has always mastered the profession of winemaker with 100% passion and rarely showed me the difficult sides. My brother went the same way and I saw every day how happy he was with it. My mother and stepfather have always supported me. I was always free in what I do and I chose the most beautiful profession in the world.”

At first, Kilian seemed set to tread a different course: “My parents put a lot of energy into the recultivation and suffered a lot. For me it was clear that this work is not just sunshine. So I decided to study something else. But when my parents reaped the first fruits after recultivation, I knew: that will be my life, too. I did not have to ask my wife if she was going this way with me: there would never have been another way for her.”

When Kilian and Angelina were called home to take over the estate, Kilian says, “For a while, we tried to balance study and the winery. Unfortunately, that did not work very long.” They hired Angelina’s brother and asked Kilian’s uncle and other winemakers to “show us how everything works.” It was a very difficult time. “The sadness, the terrible autumn of 2010, the setbacks.”

Little by little, Kilian says, “We learned and we grew in our tasks. We exchanged views with many winegrower colleagues. No matter if Reinhard Löwenstein, Clemens Busch, Johannes Leitz, Julia Bertram or Benedikt Baltes. Everyone stood by us in word and deed.” They have now made Franzen truly their own — though they are the first to give credit to everyone else.

“Today we have a job that requires a lot of time,” Kilian explains. “If we make some free time, then for our daughter. She is our happiness. She explains the world to us and opens our eyes every day. We are the fifth generation to make wine here, and hopefully she is the sixth.”

Region

Bremm sits about midway between Bernkastel and Winningen, at a point where the Mosel pulls into a tight bend and the Calmont rises imperiously above its north bank. The Calmont itself stretches some 2 kilometers (1.2 miles), forming what is essentially an enormous concave mirror, open to the south. The mountain rises some 400 meters (1,300 feet) above sea level, and its summit, covered in trees and shrubs, shelters the valley from northern winds and cold. To stand at the Mosel’s edge and look up at the Calmont, the cliff appears “almost threatening,” Kilian acknowledges. “Many passages, even steeper than 65 degrees, rise almost vertically. The steepness can only be grasped once you climb into its terraces. There is no single contained vineyard, but rather sections of earth, intermingled with steep rock walls and rough ledges. To make the cliff useful for cultivation, growers built terraces with support walls. However, these walls, unable to withstand the pressure of the mountain for long, collapse, and must be constantly repaired or rebuilt.” The terraces are also essential for retaining the sun’s warmth to moderate diurnal shifts and for guiding the vines’ root systems into the slope.

You would think such terrain would have earned the wines of this region renown, not obscurity. But, as Kilian explains, “the Calmont remains a secret among wine connoisseurs, partly because its size yields tightly limited quantities. Everywhere in the world, the Mosel is known for its steep slopes and riesling grown on slate. However, Mosel does not equal Mosel. There are countless flat areas on the Mosel with hardly any slate. But if there is a place that is 100% steep slopes and Mosel slates, it is the Calmont. There is no better situation for riesling.”

Vineyards and farming

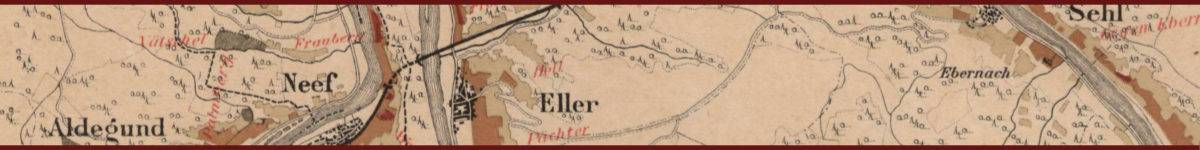

The Franzens’ vineyards are concentrated in the Calmont, with additional holdings in the Neefer Frauenberg and Kloster Stuben just opposite. The Frauenberg and Kloster Stuben (the former Augustine monastery that thrived here for six centuries before secularization) are sited on a hilly peninsula formed by the Mosel’s hairpin bend, offering a second, though less dramatic, bank of south-facing vineyards.

“We now have a little more than 10 hectares in total — about 5 just in the Bremmer Calmont. The largest single parcel is the Fachkaul, with its now 1.8 hectares. Bremmer Calmont has about 12 hectares in cultivation. The remaining seven hectares are shared by about 20 other winemakers,” Kilian notes.

The Calmont vineyards are dominated by quartzite and red slate, the color coming from oxidized iron content. The ground here warms faster and stores heat better than elsewhere in the Mosel due to the optimal exposition, numerous rocks and walls, and high percentage of stone in the soil. Kilian points out: “The slate stores the sunshine during the day and releases it to the vines at night. Throughout the terraces, the foliage walls cast no shadow so each leaf can absorb the heat.” The vines’ root systems struggle for water and cope with limited supply by giving lower yields and smaller berries, making the Calmont wines in Kilian’s words, “a bit more powerful, a bit wider, and with a little more character.”

By comparison, the Frauenberg has more weathered gray slate, with more humus and smaller rock fractions, making the Frauenberg wines, as Kilian sees it, “finer, with slightly more fruit and finesse.” This is also where the Franzens have their oldest vines, ranging from 60 to 90 years old. For the estate wines, such as Quarzit Schiefer, Kilian “likes to take the vineyards from the part of the Calmont exposed a bit east. The wines are a bit clearer, a little less complicated, and a bit easier to drink.” Kloster Stuben is a lower, sandier site, well suited to the earlier-ripening traditional variety of the Lower Mosel: age-old elbling.

“We spend a lot of time and work in the vineyards. It all starts with well thought out pruning, lots of foliage and ground work,” explains Kilian. “In older vineyards, we still have a lot of single pole training. In the newer vineyards, we have moved to wire frames.” For the moment, Kilian says, “climate change is still OK for us. Every year we adapt to the current weather. If it is hotter and drier, we leave more leaves on the sunny side and take them away on the shaded side. If it rains a lot, we give the vines more possibility to dry quickly by more defoliation.”

No roads lead through the Calmont, only narrow paths that wind across the mountain and stairways that climb over the terraces. “Machines could never be used. On the back of the wine grower, fertilizer is transported up in the spring and grapes carried down in the fall,” Kilian makes clear. “The effort of the wine growers is arduous and the expenses involved with the cultivation and preservation of the vineyards on the Calmont have always been high.” To do this work is truly a calling. “We prune, tie, harvest, then fill about 60,000 bottles of wine each year — and love every single one of them. Our life is a succession of many small and some larger, often dramatic, events, which the vines store as information in their grapes,” Kilian muses. “These moments leave traces in our riesling.”

In the cellar

“When we took over the winery, we wanted to do everything differently. We saw only what we had newly learned at Geisenheim and wanted to upset everything. We had to realize that much of what was old was good. We did not stick to old data for the perfect reading time, but turned to the grapes. We reap maturity rather than time. We want lighter, clearer wines that retain their character, not feel heavy. The wines should decide in which direction they develop — not us,” notes Kilian.

In the cellar, grapes are foot-crushed in large boxes and macerated for two to four hours. After that, Kilian explains, “we really try not to interfere in the fermentation. In healthy years, we like to work with mash time, press very gently, and allow the must to settle for one night. Then the clear must is poured into stainless steel tank and we wait until fermentation starts with the wild yeasts. It challenges us, requires patience and time. Of course it can go wrong -– and sometimes does. Our riesling “Zeit” is the best example of this. A wine can bubble for almost two years. But that’s OK for us. Sometimes the wines also taste difficult, my wife would say ‘awful.’ But so far, these have come to be really great wines.” Beyond this, there is no fining and SO2 is used to prevent oxidation. The estate wines are usually bottled between February and April, the vineyard wines between May and July. The GGs only after the vintage. “But even there,” Kilian cautions, “we do not always go to the calendar, but to the feeling. And the wine.”

The wines are nearly always dry. But, Kilian explains, “Every year, one tank takes forever, and what can we do? We wait and wait and if it doesn’t get dry, it must be where the wine wants to be.” In 2015, they decided to start bottling the results as “Zeit” (“time,” in English). Though extraordinary today, the wine harkens to a time when this kind of élevage was normal. The 2016 version fermented for more than 400 days.

A key element to this overall approach is allowing the wines to go through malolactic fermentation as well.

Malo in riesling

If you talk malolactic fermentation with 10 riesling producers, nine will say, “That’s not what we want in our wines. We like purity and finesse.” One will tell you, “Yes, our wines go through malo — if it’s what nature wants.”

Malo in riesling is completely misunderstood in the U.S. and possibly nearly everywhere else. People tend to think it dulls the precision for which riesling — above all of the Mosel — is cherished. Many also believe riesling’s high acidity to be inimical to the lactic acid bacteria that cause malo. You’ll hear a pH of 3 bandied about as the number below which malo “doesn’t happen.”

In fact, malo can and does. It is part of some producers’ expression of terroir and can contribute a rounder acid profile and richer texture to riesling. It’s also quite possible that malo occurs in riesling far more often than we or even the winemakers — not all of whom control for malo — know.

Malo is not a true fermentation at all, but a bacterial conversion of malic acid to lactic acid. The lactic acid bacteria are typically on the grapes when they come into the cellar from the vineyard. But, as in the Franzens’ case, they can also be in the cellar. Primary alcoholic fermentation and the addition of SO2 at crushing significantly reduce the bacteria population. But by spring following harvest, nutrient and free SO2 levels typically have tipped back in favor of the resurgent bacteria, just as cellar temperatures begin to climb to a hospitable degree, allowing malo to occur.

There is much more at play than pH alone: Temperature and rate of fermentation. Timing of malo relative to primary alcoholic fermentation. Lees exposure. Early versus late bottling. And of course, timing and levels of SO2 additions. These factors can partially or fully block malo or alter the perceptible sensory effects of malo on the wine.

In discussions of malo in riesling, most consideration is given to its effects on acidity. According to research reported by Jamie Goode, malo increases pH by 0.1 to 0.3 units and reduces total acidity by 1 to 3 grams per liter. There are also concerns that it may add nutty or buttery aromas. But when managed correctly, malo can offer a desirable roundness of acidity and textural complexity. And malo’s characteristic aroma and flavor impacts, it turns out, can be absorbed by the lees, given adequate exposure.

(To be clear, here we’re only talking about spontaneous malo in dry riesling. Off-dry styles generally require SO2 additions for stability at levels that block malo.)

The Franzens are not the only Schatzis who let their dry rieslings go through full or partial malo: Stagård, Dreissigacker, and Knebel do the same. For their part, Kilian and Angelina say, “We work with malo. This is not really typical for Mosel riesling, but exactly what makes our style. Our spontaneous fermentation is very slow (up to 23 months). Our malolactic fermentation runs parallel to the alcoholic fermentation. It is part of our philosophy of giving the wines space and time. Ph is certainly one of the reasons for the malo. The other is the flora of lactic acid bacteria in our cellar. We have been doing malo for 30 years. The malo tastes and aromas are absorbed by the yeast. For us, the best case is if you do not smell or taste the malo at all.”

There is debate as to whether malo belongs to the historical style of the Mosel. Some argue that up until the 1890s, this was the norm for the dry wines. Others contend acidity levels of the time would have made this impossible. What matters to the Franzens is that malo is inherent to their terroir and style. They wouldn’t have it any other way.