Marcel Zanolari

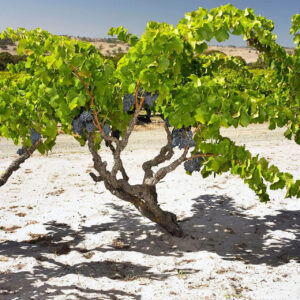

Valtellina clings to the stony reaches of upper Lombardy, where distinctions between Italy and Switzerland subsume to the forces of nature. This long, narrow Alpine valley, Italy’s northernmost wine-growing region, is characterized by imposing peaks, dense forests, and, as far as the eye can see, dry-wall terraces zigzagging across its steep north slopes. Over the course of two millennia, the terraces (laid end to end totaling twice the length of the Italian peninsula) have been built and rebuilt, always by hand — a monument to the unbroken resolve of generations to grow wine in this place. Here, on 10 hectares of vines above the single-steepled village of Bianzone and scattered along the valley further east to Tirano, Marcel Zanolari has dedicated himself to biodynamic farming and making “living wines.” Marcel believes “nature is at the center of all work and man is the respectful observer and carer of the delicate balance of the ecosystem.” Putting this conviction into practice in the vineyard and in the cellar yields wines that could come from nowhere and no one else.

It’s telling that Marcel deflects attention from himself toward something much larger —“connecting people, society, and land through sustainable agriculture.” It’s also what makes him a Schatzi. In talking with Marcel, it quickly becomes clear that his many passions, including hiking and paragliding, all tie in to his dedication to working with, not against, nature, and to sharing his learned experiences so that others can benefit. This approach has earned his estate Demeter certification, one of the strictest in biodynamics, and recognition as the first Italian winery to become a B Corp, a certification that requires adherence to rigorous social and environmental standards.

The estate

Marcel’s interest in winemaking started as a teenager, when he began learning from his visionary father, Giuliano Zanolari. “In the 1980s,” Marcel explains, “on two experimental patches of land, my father made the first attempts at cultivating vines with a method that avoids all synthetic fungicides. For about 15 years, he carried out his experiments on nebbiolo, pinot noir, and cabernet sauvignon vines.” Encouraged by this work, Marcel started a small farm in Bianzone in 2001. “At the beginning, I always told myself: Wait and see. About every ten years you will lose your harvest. Recalculating now, we have lost more than that” — including his entire crop in 2008. Over time, Marcel has added parcels in and around Villa di Tirano, Tirano, and Telio. Mixed crops and small livestock (geese, goats) are part of his vision for closed-cycle agriculture, though the terraced terrain makes these aspects among the most challenging.

The region

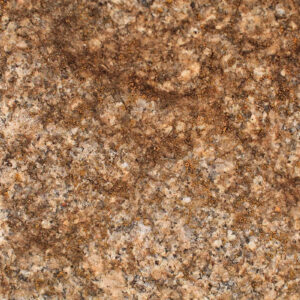

Valtellina is an east-west valley, whose south-facing vineyards have been planted to capture the region’s abundant sunlight, moderate rainfall, warm days, and cool nights. The Rhaetian Alps to the north shelter the vines, while a steady, gentle southern wind brings air flow essential to this humid river area. But viticulture would be impossible here without the terraces and their unique sandy, gravelly soils. Starting with the Romans, through to this day, the vineyards of Valtellina have depended solely on human effort for the thin topsoil that overlays the terraces. Over the centuries, laborers have excavated innumerable loads of riverbed soils from the valley floor and hauled them up, one by one, into the terraces — all in an unending effort to maximize the plantable vineyard area. Maintaining the terraces and their soils is a never-ending task, as both are prone to damage from heavy rainfalls (more frequent now with climate change) as well as training of artisans to do the work.

The staggering number of work hours required to farm vines here by any method, let alone biodynamically, has shrunken the vineyard area of Valtellina considerably in the last century or so. Countless vineyards have been abandoned to forests steadily encroaching from the hilltops. The average parcel size is now just .65 hectares. To counter this, Marcel works with a team of “local boys without vineyard experience but with more passion for the nature and wine” with the aim of inspiring them to keep the terraces in active use — an act of faith in the future.

The vineyards are overwhelmingly planted to nebbiolo, known locally as chiavennasca. Genetic research has revealed a wide diversity of nebbiolo clones in Lombardy, suggesting this, not the Langhe, is the grape’s original home. Valtellina’s main biotype is nebbiolo rosé, prized for its hardiness, including resistance to millerandage and berry shatter (useful in Valtellina’s cold, rainy springs) and to drought (frequent in the region’s dry, hot summers).

Sforzato (Italian for “strained”) is a local production method as much a part of the character of Valtellina wines as the vineyards themselves. In this process, select nebbiolo grapes are raisined for about three months in the appassimento method, over straw trellises in drying sheds. This process of concentration was once essential when not every vintage could be counted on to reach full ripeness. Now the tradition is carried on as a unique expression of the region.

In the vineyards

Roughly half of Marcel’s 10 hectares are planted to nebbiolo, with the rest divided among pinot noir, cabernet sauvignon, riesling, and pinot blanc, using disease resistant clones. Vine age ranges from 20 to 60 years. High elevations (350 to 750 meters, or 1150 to 2500 feet, above sea level) and sandy, gravelly granitic soils control yields. Vine rows are planted north-south to maximize sun exposure.

Marcel explains: “On our farm, we are inspired by the principles Rudolf Steiner suggested in the early 1900s to restore vigor to lands that were already impoverished and exploited at that time.” Since converting to biodynamics, Marcel has observed that his “soils have changed color and texture. There are no more problems of drought even in dry vintages because the soil is much more alive, requires much fewer treatments, and slowly gives more quantity year after year. The grape skins are healthier and allow very, very long macerations. They have a more vital and positive energy.”

“To embrace the biodynamic method means to accept a substantial reduction in productivity, especially to begin with as the balance between terrain and plant has not yet been restored. The choice of adopting the biodynamic principles in this initial phase of ‘unbalance’ is a risky one, especially in an area such as Valtellina, which is also conditioned by the asperity of the land. We can however overcome all obstacles by remaining strong in our fundamental ideals and being animated by passion, belief and motivation,” says Marcel.

In the cellar

Valtellina’s nebbiolos tend to be lean and sculpted, delicate and floral — paler, less tannic, higher in acidity, and altogether lighter on their feet than their more famous Langhe counterparts. Marcel works with, not against, this style. He is fascinated by traditional winemaking methods and unafraid to explore new ones. “It is not always easy,” he observes, “to obtain a ‘live’ wine that expresses all of its potential and shows the particular qualities dictated and influenced by the climate of the season,” but precisely that is his aim. “Often we have to learn again to discover lost flavors, in our case, those of wine.” Marcel is patient. He knows his wines are often initially closed, but with a few hours, they open. “The wine is always in motion.”

“All our wines are de-stemmed and undergo a process of maceration with the skins,” explains Marcel. “If the health of the grapes permits, we prefer long macerations, from a few days up to a couple of months.” Spontaneous fermentation happens primarily in steel tanks and amphorae. “In both cases we use the submerged-cap fermentation method. The length of fermentation depends on the year’s harvest and the development of the natural yeasts present on the individual grapes,” Marcel notes.

Marcel regards each of his wines individually. “Every typology requires its specific aging journey,” he explains. All red wines are aged for a minimum of 24 months, with additional bottle aging of about 12 months.

Nebbiolo Valtellina Superiore is sourced from vines that have been in production since 2001, some of which are air dried on the vine. Spontaneous fermentation is carried out in stainless steel tank, and after malolactic fermentation, the wine is transferred to second- and third-use barrique for 36 months of aging.

Sforzato Valtellina Superiore also comes from nebbiolo vines in production since 2001, dried in the local tradition, through which 25% of the grape’s water weight is lost. The partially dried grapes are then briefly cold macerated, spontaneous fermentation is carried out in stainless steel tank, and after malolactic fermentation, the wine is transferred to used barrique, as above.

Sforzato “Le Anfore” is likewise sourced from partially air-dried nebbiolo that is then raised in clay and cement amphora. Marcel has selected amphora for this bottling for the “correct roundness it gives to the wine, without introducing the scent of wood and its derivatives,” as he puts it, and for the vessel’s ability to maintain a cool constant temperature in normal cellar conditions.

Uvaggio Rosso is a blend of native and traditional red grapes that sees two to three years in used wood cask and amphora, followed by 18 months in bottle.