“Nobody will give you ‘the recipe.’ But you can learn a small detail every day.” — Mitja Sirk

A family legendary in Friulian hospitality. A young son reevaluating Friuli’s vinous heritage through the lens of experience with Gravner, Conterno, Dujac, and Roulot. A single traditional variety. A fresh, distinctive voice. That voice, that son is Mitja Sirk. His wine story opens with an extraordinary chapter. At age 11, with Josko Gravner’s encouragement, Mitja made his first wine. Over seven vintages, under the master’s eye, he refined his understanding of Friuli’s past and potential. With time, his focus has narrowed. He now works with one grape — friulano — in a single style. He seeks out old vines, ponca soils, traditional trellising, clean farming. In the cellar, he has moved away from extended skin contact and amphora, towards stainless steel, long lees aging, and batonnage, to make a wine that is, in his words, “very clear and direct.”

The Sirks of La Subida

The Sirk family, Josko and Loredana, and their grown children, are originally from Slovenia, but have been at home over the Italian border in Cormons for more than half a century. “My father ran the estate until the 1974 vintage,” Mitja explains, “but he decided to move his attention from farming to the [now Michelin-starred] restaurant and the [now world-renowned] hotel, La Subida. For 30 years, the vineyards that we own were worked by our cousins. Finally, in 2003, we took them back for vinegar and wine production. Vinegar production is my father’s big passion,” notes Mitja. “I restarted the wine production in 2016, as a project based on working exclusively with friulano, the typical variety of our region.”

Mitja Sirk

“I realized I wanted to be a winemaker when I was 11 years old, visiting a local winegrower called Josko Gravner,” Mitja relates. “He took me under his arm and said that he would give me one of his clay amphorae. He did! And one month later he brought some grapes. My first wine was made.” Mitja went on to study at the local viticulture and enology high school, though he was discouraged by the “quite retro” approaches he saw there. He resolved to travel and learn directly from winemakers he admires throughout Europe. “I think that a smart and interested wine producer or wine lover wants to learn from as many other wine people as possible,” he says. “Each visit, each dinner, each talk can be helpful to discovering a new way of doing something. Tasting regularly with my best friend Kristian Keber, Edi Keber’s son, helped me a lot to understand better Friulano and its nuances. I staged at Dujac in 2013 and Conterno in 2014, as well as Isole e Olena in 2011 and Roulot in 2018. Nobody will give you ‘the recipe.’ But you can learn a small detail every day. The cleanness that Conterno wants in his cellar even during harvest is incredible. The experience and confidence that Jean Marc Roulot has with his vineyards, unbelievable. The simplicity and history of Dujac gives you the feeling, even if you are there just for a couple of weeks for a stage, that you can make that history as well.”

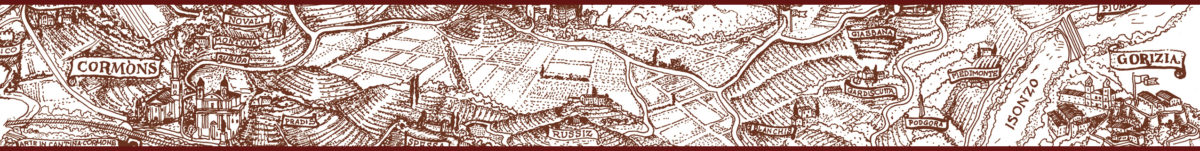

Cormons in Collio

The town of Cormons is just a mile from the Slovenian border, in the horseshoe-shaped region of eastern Friuli referred to simply as Collio (“hills”). It is a place defined by confluences. Midway between the Julian Alps and the Adriatic Sea, it is, Mitja notes, “a classic Mediterranean region, warm in summer, but, as a classic Alpine area, cold and wet in winter” — ideal conditions for the thin-skinned but early-ripening friulano. Culturally, Collio has long been an area of overlap for Italian, Austrian, and Slavic influences. “The best part of Friulian wine is the diversity,” Mitja told Levi Dalton in a 2016 interview. “I think history makes the decision for us. We were first under the Venetians, so we were selling the wines there. The best period was the Austrian Empire because we were the warmest for vines. Then the ‘60s and ‘70s brought us to increase production of international varieties.”

The successive dominance of empires and republics here has left the region with a multifaceted identity and a miscellany of varieties. Cormons remained under Habsburg rule until the end of WWI, leading to a preponderance of “noble” varieties, including sauvignon vert, which became tocai friuliano in its adopted Friulian homeland. (It has since been shorn of its tocai prefix by legal action from the Hungarians). The grape is traditional and widely planted in Collio (though recently in decline), long prized for its aromatic delicacy pronounced mineral, floral, and sweet almond notes, with a characteristic catch of bitterness at the finish.

WWII took a heavy toll on Collio. In the postwar period, Friuli rebuilt its economy based largely on wine, but it did not emerge as a source of notable wines until the late 1960s. Since that time, the region’s winemaking identity has undulated nearly as much as its history and landscape. “Friulian” has, in turn, meant “Germanic” (clean, crisp), “Burgundian” (oak influenced), and “Georgian” or “radical traditionalist” (skin contact, amphora). Now, Mitja is putting his own stamp on a style we might cautiously term “purist” (a move toward native and traditional grapes, native yeasts, minimal skin contact, long lees aging, stainless steel, temperature control.) “In Friuli, ‘traditional’ can give many different visions,” Mitja notes.

Vineyards and farming

The soil is relatively consistent throughout Collio. “It is a type we call ponca in Italian and opoka in Slovenian,” Mitja explains. “It looks like a series of compressed stones, made of hard, compacted sandstone and marl. On the surface this stone breaks very easily. This broken stone will mix with the organic matter and the clay portion to create a very good growing environment.” Ponca brings pronounced texture, concentration, and extract to friulano, a variety that tends to delicacy. “We try to find old vineyards for the single vineyard parcels. That is not easy. Our oldest was planted in the 1960s. I’m trellising the vines in the local cappuccino or doppio capovolto [double arch cane] style, I’m picking the grapes at physiological ripeness.” Mitja declares his farming philosophy to be “not using pesticides and herbicides as a simple and basic rule.”

In the cellar

Despite Mitja’s early start with Gravner, “I’m not doing skin contact,” he says flatly. “Josko helped me for the first seven vintages, making orange wine. I was young, but super excited. I think he showed me that wine can be made by a young child without any technology, knowledge. Just a couple of simple rules. Now I’m controlling the temperature during the fermentation, using steel vats; in the future, there will be some cement and oak barrels as well.” Mitja’s style is, in his words, “to be very clear and direct. When I started in 2016, I began by making all the wines in a very classic way. I use gentle pressing, with a cold soak overnight. Fermentation is started in stainless steel. We are moving away from selected yeasts. At the end of fermentation, we try to keep the wine on the fine lees and we work with a light batonnage — but working in steel I have to be careful about reduction [to which friulano is especially prone]. Filtration is done once, at bottling.” These early vintages show structure, elegance, and remarkable focus.