“The idea from the first day was to work the vines and make the wine just like Grandpa did: with minimum intervention and zero chemistry.” — Giuseppe Scirto

Cool climate wines from a Mediterranean island on the latitude of Tunisia? Yes. Welcome to Etna. Here, on the northern slopes of Sicily’s epic volcano, Giuseppe Scirto and Valeria Franco tend a true polyculture: 4 hectares of vines and 1 hectare of olive, nut, and lemon trees, all at 600-1,000 meters [1,900-3,200 feet] above sea level. Carricante, nerello mascalese, and nerello cappuccio planted between 1900 and 1930 in black volcanic sand and pumice soils work a slow magic. The vines can only extract nutrients over the most gradual timeframe, extending the life of the vine and concentrating a range of savory, mineral elements in the grapes and the wines. Giuseppe and Valeria’s personal history with the land coupled with the tiny, two-person scale of their farming give them a visceral grasp of grape and terroir. Working organically in the vineyards and with radical minimalism in the cellar, they bring forth wild and lively wines. Even as the wines flirt with funkiness, this is never allowed to obscure terroir expression. Giuseppe and Valeria have no formal wine schooling, but are guided by their own intuition, the teachings of Giuseppe’s grandfather, and a primal respect for their untamable terroir. The excitement surrounding Etna wines is in part the thrill of discovering a lost world, with so much of its territory and tradition intact. But for Giuseppe and Valeria, there is no rush to rediscover. They’ve been connected to this place all along.

Origins

The vineyards Giuseppe and Valeria work today belonged to Giuseppe’s grandparents, who produced bulk wine, “as everybody was doing on Etna until about 20 years ago,” Giuseppe points out. When Giuseppe’s grandfather, Don Pippinu, died in 2005, it was at a time when small vineyard owners on Etna had begun to sell off their holdings. “Ours were particularly requested because they are in a highly valued area. But I was very close to the vineyards because from a young age, I spent all my summers there together with my grandfather. Walking in those vineyards, I revived a memory. I could never sell to others the sacrifices of my grandfather, also because no price could repay a bond like that between me and him.”

“In 2009, we started to work the vineyards. 2010 was our first vintage. The idea from the first day was to work the vines and make the wine just like Grandpa did: with minimum intervention and zero chemistry. We did not study enology. Perhaps our own ‘ignorance’ initially allowed us to make this choice. Having a great passion, being connected with many other producers, and being self-educated has helped us to know more deeply the vines and the wine. In the vineyard and in the cellar, we work, just the two of us.”

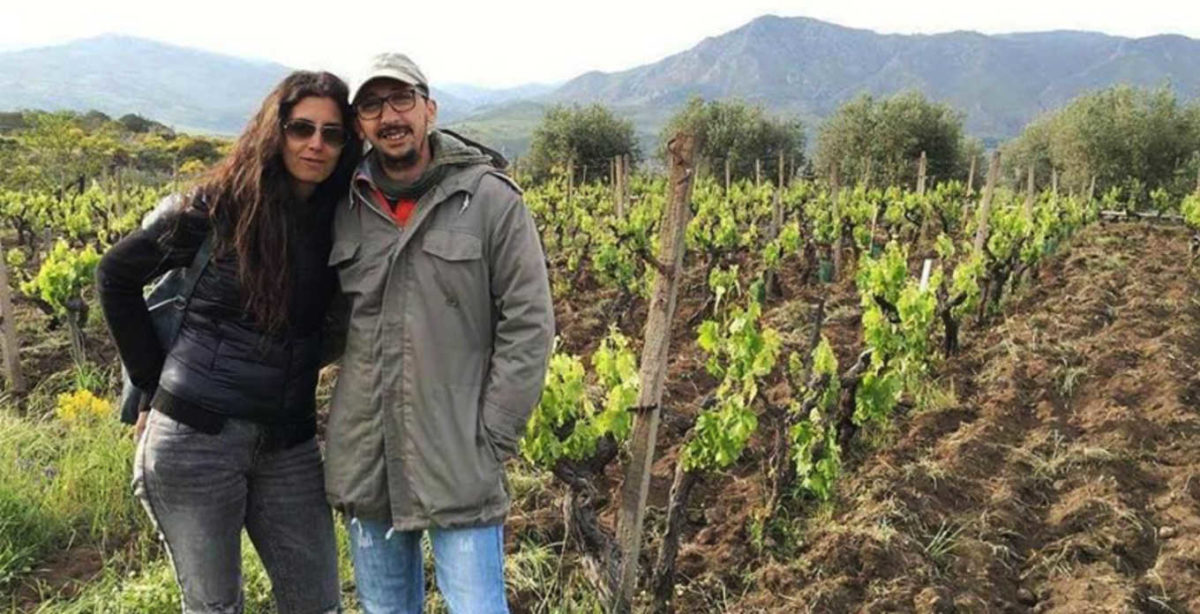

Giuseppe Scirto and Valeria Franco

“There was not a precise moment,” Giuseppe says of his realization that he wanted to become a winemaker. “I grew up with this passion, but only became aware of it a few years after the loss of my great master, Grandpa.” Giuseppe and Valeria were entwined in wine and life on the mountain before they met. Beyond his childhood in the vines, Giuseppe had also worked at Calabretta, a pillar of traditionalist Etna winemaking, where the wines evoke the principled old school of Barolo. Valeria brings to bear her heritage as one in a long line of farmers and family winemakers.

Northern Etna

“We produce wine in an area that is so different from the rest of Sicily, it is considered an island on the island,” Giuseppe notes. Etna is a stratovolcano, built layer upon layer from the seafloor to its present height of 3,350 meters (nearly 11,000 feet) above sea level over the past half-million or so years. It is one of the world’s most active volcanoes, not just at its main crater, but also in and around myriad vents and fissures that continually conduct lava flows of varying size and intensity. This has surfaced the mountain with an array of extrusive igneous rock and soil types — critically, all comparatively young and unweathered. As John Szabo writes in Volcanic Wines, even “the same volcano can erupt different lavas at different times due to changing composition in the magma below.” This means critical differences in proportions of silica, iron, magnesium, potassium, calcium, and sodium as well as rock structure from eruption to eruption, flow to flow.

In volcanic terrain, there appears to be an inverse relationship between the ages of the soil and the vine: the younger the soils are, the older the vines can become. This is due to the balanced presence, but extremely limited availability, of macro and micro nutrients in the lava rock as well as the hostile environment it creates for pests like phylloxera. Gnarled, slow-growing, centenarian vines are an Etna hallmark. Scirto’s are prime examples of the silent power they exude.

History and culture — here speaking just of the past century, not to mention millennia of habitation and wine cultivation — also distinguish wines made on Etna today. Szabo points out that countless Etna vineyards were either abandoned or cultivated solely for local consumption, lifting commercial pressures to replace low-yielding or unfashionable vines with other material. Moreover, as Italian wine scholar Ian D’Agata writes, “the fierce attachment that Sicilians have to their roots and traditions means that any input coming … from grandparents and other family members would be heeded more here than in other regions.” This keeps roots deep and generational connections vibrant.

As Giuseppe sees it, “the advantage of our region is definitely of being in the south of Italy, but at the same time of being in the mountains. This greatly helps the thermal excursions. Moreover, our volcanic soils have the particularity of good drainage. Humidity is very low, so very few diseases proliferate, even though the rate of rainfall here is higher than the rest of Sicily. Our vineyards, even if close to each other, are quite different, as they are formed by stratifications of different lava flows, so we have some vineyards with deeper soils and others with more pumice.”

The north slope of Etna is somewhat cooler than the vineyards that wrap around all but the truly inhospitable west side of the volcano. But here, altitude is more significant than exposure. It impacts not only temperatures (lower) and rainfall (wetter), but, as Giuseppe notes, soil depth, too. Soils are deepest where lava flows have been most frequent and abundant, that is, closer to the top of the volcano.

Vineyards and farming

Sicily’s native varieties are intrinsic to the island’s self-expression. And few grapes are better adapted to the austerity and intensity of Etna than carricante, nerello mascalese, and nerello cappuccio — at Scirto, all alberello trained, per local custom. Giuseppe and Valeria have a half hectare of carricante, Etna’s principal white grape, aptly described by D’Agata as “a hermit that loves mountainous altitudes.” It is perfectly at home in the higher climes of Etna — and virtually nowhere else in Italy or the world. Low yields from the old vines at Scirto bring intense stoniness and salinity to the wines, with marked acidity, tempered by letting the wines go through malo, as Giuseppe and Valeria do. Carricante is sometimes compared to dry riesling, especially in regard to the flinty register expressed by older bottlings.

Nerello mascalese is an almost one-to-one match with nebbiolo in its high acids and tannins, low pigmenting anthocyanins, late ripening, terroir articulation, and ability to age into grace and nuance. It is thought to be a natural crossing of sangiovese and mantonico bianco, a Calabrian white variety marked by high tannin and acidity levels. Nerello mascalese is vigorous, but responds sensitively to terroir, planting density, and training method. It tends to give wines of savory mineral character underscoring red cherry and herbal notes. Nerello cappuccio plays the perfect counterpart to mascalese. The complementarity of the two starts in the vineyard, with staggered bud break and harvest times. Cappuccio is far less widely planted, more muted in its terroir expressiveness, lower in tannin and darker in color, easily explaining its selection as the traditional blending partner for mascalese.

Working such a small area, Giusseppe and Valeria are acutely attuned to the ways in which the intersection of altitude and soil type affect their trio of varieties. “For example,” Giusseppe says, “our Don Pippinu comes from a vineyard at 700 meters above sea level with very deep soil and pumice, giving wines that are more structured and longer aging. A ‘ Culonna grows in our primary vineyard, 100 meters lower, in Contrada Feudo di Mezzo, where the ground is very rich in pumice, rather than rocks. And our white is a blend of grapes that we collect from all our vineyards.”

In the cellar

“Our philosophy is quite simple: minimum intervention! We believe that if you work well in the vineyard and you farm healthy grapes, there is very little to do in cellar. Our wines are all born from spontaneous fermentations in stainless. We decide the days of maceration according to the vintage (we have no protocols), all the wines do malolactic fermentation, and we only bottle when we are ready. All our choices depend on the sensations we feel every time we taste from the tanks. Even the decision of whether or not to add sulphites is a very sensitive one. In cases where we decide to add, it is always under 40 mg/l.”

The carricante see three to five days of maceration and zero added SO2. It is raised for 10 to 12 months in stainless steel before bottling, accentuating alluring and incisive aromas of orange peel and pink peppercorn. A’Culonna Etna Rosso DOC is named for a volcanic rock column that serves as a local meeting place in Passopisciaro, where Giuseppe’s grandfather used to take him as a boy. When visitors came to town looking for wine, they’d see Giuseppe’s grandfather sitting by the column and ask him where they could buy wine. His grandfather was only too happy to oblige and led the visitors to his own cantina. Scirto’s Rosso honors this memory. Giuseppe and Valeria make the wine at Calabretta, where they allow it an extended maceration (10- to 45-day, depending on the vintage), spontaneous fermentation in stainless steel, and elevage in 2000L Slovenian oak botti for 18 months and in bottle for a further six months before release.

“Compared to previous generations, the differences between my generation and the previous one relate mainly to the way of working in the cellar,” Giuseppe asserts. “In fact, we continue to work in the vineyard as our grandparents did, without using chemistry and most of the work we do manually. In the cellar, we do longer skin contact and aging. We use mainly steel and do a lot of cleaning because that is one of the things we care more about!”