“Single vineyards are the essence of all our efforts. Just by focusing on them you can work on the marginal differences offered by the diversity of soils. That’s what wine is all about: details, subtleties, and character.”

—Urban Stagård

When Urban and Dominique Stagård took over the family estate in 2006, they set straight to reimagining its potential. Their vision had four elements: reclaiming obscure vineyards, reexamining the possibilities of iconic sites, farming based on a close study of soils, and making wine by drawing on knowledge and techniques of the past. Some of these approaches—such as the use of Steinzeug, or thick-walled stoneware fermentation vessels—are so arcane their rediscovery feels more like innovation. Riesling, the variety the Stagårds say “speaks most to us,” is their clear focus. Grüner veltliner, more traditional and far more widely planted in the Kremstal, naturally finds a place in their work as well. Both varieties are grown organically (certified since 2009) on 17 hectares of exceptional sites scattered around Stein and in the Wachau. The Stagårds are dedicated to amplifying biodiversity and intensifying hand work among the vines, and restoring traditional practices to their ancient cellar. They rely on native yeast fermentations and minimal sulfur, as well as long aging on the fine lees to promote texture and protect against oxidation. They also embrace skin maceration and stem inclusion when they feel this contributes to site expression. “Above all,” says Urban, “we trust in time.” This allows each wine to find its own individual rhythm and equilibrium. These are true wines of terroir – crystalline, tense, and intellectually satisfying, not to mention delightful to drink.

Lesehof Stagård

The Stagård cellar is nearly 1,000 years old. While you pause to take that in, a few details: Dominique says wine was not made here continuously, but documents show that Benedictine monks planted this land with a mix of vines and apricot trees. The estate, first mentioned as “Lesehof Tegernseer,” dates to 1424 – making it roughly as old as the village of Krems itself. In 1786, the winery came under the ownership of the current family, who continued to grow grapes and produce wine under the “Tegernseer” name. Then in 1981, Kenneth Stagård traveled here from Sweden and married into the family. He and his wife, Elisabeth, started the Swedish branch of this estate and renamed it Lesehof Stagård. Kenneth’s son, Urban, and Urban’s wife, Dominique, took over in 2006, making them the seventh generation to run the estate. They immediately began the crucial transition to organic viticulture, with certification gained in 2009.

Urban and Dominique Stagård

The Stagårds, along with their young twin daughters (born in the Mosel as it happened), are keenly aware that they’ve stepped into “a lot of tradition and also the duty to continue,” as Urban puts it. Urban came to Austria from Sweden when he was seven, started oenology school at 15, and then went on to work in Luxembourg at Domaines Vinsmoselle and in Austria at a few small wineries near Stein. He also put in some time at Wein & Co, Austria’s biggest wine retailer, to round out his understanding of the wine market. In 2005, he took a class in organic winemaking, setting him on his present course. He loves German riesling (“and also German winemakers!”), among them fellow Schatzis Johannes Leitz and Matthias Knebel, as well as Andreas Barth, Mark Barth, and H.O. Spanier. Dominique does not come from a wine background, but her training in marketing and administration fits in smartly with the family business, which she’s been part of since 2003.

As a family, the Stagårds are closely attuned to the abundance of life in and around the vineyards. Given the history of the estate they work on every day, long-range thinking is elemental. This combination has made them pioneers of organic farming in the Kremstal. Their emphasis on soil health also stems from their belief that a site’s distinctive character can only be expressed if the soil is fully alive. This all goes hand in hand with their relationships to local monasteries, which have enabled them to lease some of the most iconic and sought-after sites in Stein: Hund, Kögl, Pfaffenberg, and Gaisberg. Urban and Dominique have folded these old-vine parcels into the Stagård family estate, growing it from just 4 hectares to its present size of 17, which has allowed them to increase production in an extraordinarily thoughtful way.

The Kremstal and the Wachau

This part of Austria is quite Burgundian, down to the unique qualities of its many lieux dits, strong influence of monastic tradition, and domination by two varieties – writ small and rocky on the banks of the Danube. The Kremstal is split into three zones: the city of Krems, the eastern areas, and the villages on the south bank of the Danube. The Stagårds work with parcels in all three. Their mindset is that riesling and grüner veltliner are what hold together and give clear identity to such diverse topographies, microclimates, and soils.

Riesling, on the steep slopes of primary rock that rise from the Danube here, accounts for just 10% of Kremstal vineyard area, making it the subject of extreme focus. Two of Austria’s most acclaimed Riesling vineyards, Hund and Pfaffenberg, are in Stein. The Stagårds vinify parcels of both. They also work with the extraordinary sites at Gaisberg, Kögl, and Schrek.

Deep loess banks to the north and east of Krems explain why grüner veltliner dominates the valley, as the grape thrives in the water-retaining loess, protecting it from hydric stress and giving it tension and finesse.

Climatically, the Kremstal, like the Wachau, is at the crossroads of dry Pannonian warmth from the east and cooling drafts of Alpine air from the north, all moderated by the temperature-regulating effects of the Danube’s large surface area. Though it is slightly warmer than the Wachau, it experiences the same diurnal extremes that account for the freshness and aromatic intensity of the region as a whole.

Vineyards and farming

“Working organically,“ says Urban, “means above all to observe, because it is possible to read the soil: its breakages, its compressions, its root penetration. All the things that happen in the soil and on its surface are fundamental for every other development in the process of wine production. This is why we try to understand every detail of our vineyard, to know all of our vines and to treat them as gently as possible.” The Stagårds use no herbicides or pesticides, work strictly by hand in the vines, pick relatively late, and select intensively when it comes to the quality of fruit that goes to the winery.

In the cellar

“Our idea of organic winemaking does not end at the cellar door,” say Urban and Dominique. “We work with minimal intervention and, above all, we trust in time. That’s why we leave our wines on the lees for a long time – to harmonize structure, give them stability, and embrace their own specific character. In addition to heavy sorting, 10% of the fruit is manually de-stemmed for the single parcel wines. The grapes macerate up to 48 hours before they are pressed and begin their spontaneous fermentations. The ferments take place in stainless steel or, in select cases, Steinzeug.”

The Stagårds are not focused on producing wines that fit into the classic categories of “dry” or “sweet.” They normally finish with +/- 5 grams of residual sugar and fall between 12.5 and 13% alcohol, showing a certain Germanic influence and making them laser-sharp, mineral expression of poise and elegance. They have three lines: Handwerk, single sites, and Tradition. Within each line is an impressively pinpointed assortment of bottlings, expressing a different facet of Kremstal or Wachau terroir and winemaking.

Handwerk grüner veltliner originates in a selection of the Stagård’s south-facing mountain and terrace vineyards, all in the Pfaffenberg. It’s a steep site that climbs to 300 meters above sea level (about 900 feet) on the south bank of the Danube near Mautern (very near where fellow Schatzi Georg Frischengruber explores the terrains of Rossatz). The wine is fermented in stainless steel and shows veltliner’s classic snappy crunch and cayenne spice.

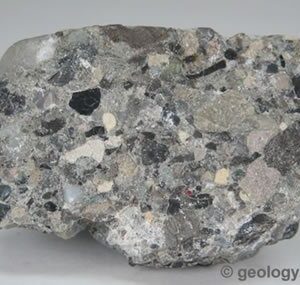

Handwerk riesling also comes from parts of the Pfaffenberg, including the Braunsdorfer terrace, which rises 400 meters above sea level (about 1200 feet) on Urgestein, here primarily schist and gneiss soils. It is also sourced from lower terraces below the Schreck, where there is more blue slate, and from sites near Mautern. The wine is fermented in stainless steel, yielding a briny, linear riesling, showing lime oil, cherry and citrus.

“Single-vineyards are the essence of all our efforts,” say Dominique and Urban. “Just by focusing on them you can work on the marginal differences offered by the diversity of soils. And that’s what wine is all about: details, subtleties, and character—what the particular vineyard can tell about a wine.”

A quick tour is in order, starting with Grillenparz. The Stagårds believe riesling grown on this wildly precipitous slope belongs to the very best of the Kremstal. “The terraces are narrow and extremely difficult to work,” Urban says, “as there is very little topsoil and the crystalline rock below can be treacherous.” Riesling from this site is a bit of an outlier for the Stagårds – rounder, with a hint of marzipan aroma, though the predominant aromas are savory and of apricots.

Schreck is steeper still – the most sharply angled of all of the Kremstal sites. Everything must be done by hand here and the yields are naturally low. The soils are blue slate and there is something particularly Germanic in this wine. Like the best of Germany’s dry rieslings, Stagård’s are detailed, pure, and juicy, displaying apples and a hint of apricot stretched over a linear structure. (A parcel of Schreck will be replanted in coming years with riesling cuttings from a trio of Schatzis: Johannes Leitz, Killian and Angelina Franzen, and Matthias Knebel.)

Nikolaihof made Steiner Hund famous. It’s a loess and loam site over conglomerate and it can produce powerful riesling. Instead of oxidation to balance the intensity of the site, Urban preserves the freshness with spontaneous fermentation in steel. The result is a yin-yang riesling of intensity and elegance, depth and lift, concentration and utter drinkability.

Kögl is pure Glimmerschiefer (mica-schist), and it produces some of the most structured wines in the Kremstal. There are five terraces of 60-year-old vines here that Urban harvests and macerates for 48 hours before pressing with the stems. He does this in healthy years because ripe stems contain antioxidants and because he likes grip in his riesling. He wants you to feel the wine all the way down to your gullet. This riesling spent ten months on the full lees before racking, and was sulphured only twice: once after alcoholic fermentation and again after racking. It is carries the most texture, hold, and length.

Gaisberg consists of 12 terraces surrounded by trees and bushes that act like a clos. It’s one of the warmest sites in Stein, situated very close to the Danube, benefiting the full effect of the river’s solar reflection. Like the Kögl, it is all Glimmerschiefer and it, too, undergoes 48 hours maceration before pressing with the skins. The palate is salty and schmaltzy with cayenne pepper spice and lime citrus zing.

Goldberg grüner veltliner is a mouthful. Whereas the Handwerk is bright, crispy, spicy, and “green,” the Goldberg is rich, persistent, juicy, and “yellow.” The Goldberg is entirely south-facing and rises 400 meters above sea level, making it the highest grüner veltliner vineyard in Stein. Stagård’s vines there are 40+ years old. The soil consists of Glimmerschiefer, loam, and loess, and it is the site that is picked last every harvest. Urban doesn’t want a peppery or “classical” grüner veltliner from this site; he wants a complex wine that highlights this particular terroir. Urban oxidizes this wine (“to get rid of the pepper”) by means of exhaling into a hose in the tank. The wine is decidedly rich, but it is also extremely focused and precise. It is exotic, spicy, and above all, long.

The Tradition line displays the Stagård’s almost spiritual connection with knowledge and techniques of historical winemaking in the Kremstal. Steinzeug riesling exemplifies this. The family’s long connection to the local monasteries introduced them to a very traditional fermentation vessel: the Steinzeug. This is a glazed, earthenware cylindrical vessel local monks historically used to ferment beer. Urban uses them because they create a reductive environment that, owing to the vessel’s thick walls, never needs temperature control. The Stagård’s largest is 750 liters and more than a century old; Urban fills it with the best grapes from all of the top sites: Kögl, Grillenparz, Gaisberg, Schreck, and Hund. Those grapes are macerated for 48 hours, then 90% are pressed and used to fill the vessel; the remaining 10% are added whole cluster. The fermentation is all sponti and malo is not blocked. The wine stays in Steinzeug until May following the harvest, at which point it is moved to stainless steel, but not racked. The wine rests there until August when it is racked, filtered and bottled. The resulting wine is a treatise on riesling – razor sharp, steely, and taught, yet also dense, intricate, and long. Above all, it is juicy and lively.