“Muscadet is and will remain our iconic wine.” — Cyrille and Sylvain Paquereau

Muscadet. The bracing, salt-stung essence of the North Atlantic in a glass. A classic and still affordable pleasure. But also, in recent decades, a wine of diluted identity. Alexis Lichine, in his masterly Wines of France, saw fit to accord Muscadet a scant paragraph. Fortunately, a new wave of producers in the Pays Nantais is reviving a true understanding of both their variety, melon de bourgogne, and the precise set of soils in which it thrives. Cyrille and Sylvain Paquereau of Domaine de l’Epinay are of this movement. They represent the fifth generation of their family to work a 16th-century estate in the heart of Clisson, now an established Muscadet cru. Conversion to organics and concentration on the precise match of grape to terroir distinguish their tenure. Though we may think of Muscadet as a wine of acid-driven freshness, this is not inherent in melon, but rather a quality only brought out by high pH soils—notably, gabbro and the gravelly granite of this southernmost part of the Sevre et Maine appellation. The range at Domaine de l’Epinay focuses on melon’s terroir transparency, aided by spontaneous fermentations, minimal added sulphites, and up to 36 months lees aging in underground cement tanks. Cyrille and Sylvain’s wines urge us to look at Muscadet in the light of terroir and tradition, underscoring the wine’s capacity both for refreshing directness and more powerful, age-worthy expressions.

History

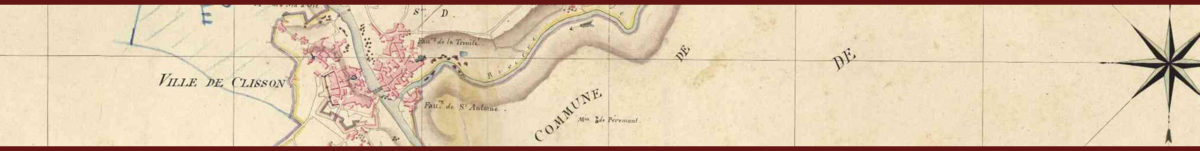

In the 16th century, Domaine de l’Epinay belonged to the Espinozas, a wealthy Spanish trading family. After the French Revolution, a local civil conflict known as the Vendée Wars resulted in the burning and destruction of many buildings and archives in and around Nantes, leaving few records. “But, we know that the culture of the vine already existed,” note Cyrille and Sylvain. “It started at the end of the 17th century, thanks to monks from Burgundy. They brought with them their grapes—especially the melon de bourgogne.” The Pays Nantais had, in fact, been a red wine region until the lethal winter of 1709. Replanting was to prolific white varieties; high-yielding melon de bourgogne, in particular, satisfied Dutch traders’ appetites for neutral base wines for their brandies. The grape flourished in the cool, damp climate and granitic soils around these parts while the presence of small, navigable rivers, all connected to the Loire and the Atlantic, facilitated the wine’s transport and trade.

Fast forward to 1900, the year the Paquereau family took over the domaine. For much of the 20th century, they managed it as a typical mixed farm of dairy, cereals, and vines. In the early 1970s, Albert and Odile Paquereau narrowed their focus to wine while expanding their holdings from 5 to 30 hectares. In 2000, Cyrille, their elder son, returned to the estate from a range of apprenticeships and trainings, and in 2006, younger son Sylvain followed, at which point the brothers took over from their parents. In 2011, Cyrille and Sylvain began the conversion to organic farming, starting with the Clisson cru holdings. Today, the domaine stretches to 52 hectares, nearly half of which are devoted to melon.

Region

Domaine de l’Epinay is a scant 40 miles inland from the sea and the quintessential maritime climate is decisive for melon de bourgogne. It is well adapted to the combination of cool, steady sea breezes and just-adequate sun. Critically, the grapes ripen fully by early September, before the arrival of the rain-bearing equinox tides.

Melon is a natural crossing of pinot blanc and gouais blanc, making it kin to both gamay, which shares melon’s famous predilection for granite, and chardonnay. David Schildknecht has pointed out that its “discreet charms easily morph into vapidity and thinness at high yields” and that “like a white tablecloth, it registers even tiny phenolic imperfections.” Therefore, scrupulous farming and strictly controlled yields are essential to coaxing melon into greater expressiveness.

Geologically, the brothers explain, “we are on the Armorican massif, an old, eroded mountain full of geological faults. This mosaic of granite, schist, mica schist, and gabbro [an intrusive igneous rock chemically similar to basalt] can make one think of Burgundian vineyards by its great diversity.” Soils are shallow, sandy, and poor but retain heat well and fracture easily to allow deep root penetration. They also tend to be basic, which elevates acidity in the grapes.

The introduction of a cru communaux (communal cru) system for Muscadet was an important step in defining terroirs and imposing new standards for yields and sur lie elevage. Clisson was among the first three cru to be classified in 2011, in recognition of its exceptional well-drained, granitic soils and the potential wines grown here have to age into power and richness.

The winemakers

“Since we were very young, we participated in the work of the family farm,” say Cyrille and Sylvain. Cyrille studied viticulture and enological technology at the local winemaking school, then added further studies, notably at Pessac Léognan (Château Pape Clement) and on San Juan Island, in Washington. Sylvain pursued degrees in science and agricultural engineering, specializing in viticulture and oenology, at schools in Angers, Toulouse, Montpelliers, and Geisenheim, Germany. To balance this with practical experience, he worked for a wine merchant in the Loire Valley for several years. Today, the domaine consists of Cyrille, Sylvain and his wife, Anne Gaëlle, their children, and a small crew. “We chose an exciting job, always surprising and rich with beautiful encounters. Wine is a link between people who like to chat and discover each other. It is in this spirit that we like to work and that we flourish,” the brothers note. They find surprising satisfaction in meeting the tests of farming in an era of climate change. “It is a reality that we winemakers notice every day. We must adapt and produce our wines in the best possible environment and try to keep the character of our wines. A real challenge for us: exciting and motivating!”

Vineyards and farming

“Muscadet is and will remain our iconic wine,” Cyrille and Sylvain assert. “We are very attached to it. We like to work its different expressions on our soils that have a lot of identity. The crucial point is harvesting at the optimal moment, adapted to varietal and terroir. Since the end of the ‘90s, we have changed many things. Our first year of organic conversion was 2011, with Muscadet. Since then, we have gradually expanded and 2018 was our first vintage grown entirely organically.”

The main idea for Muscadet at the domaine is old vines, low yields, hand harvests. The Sélection bottling comes from 25- to 30-year-old vines grown on sandy-silty soils over gabbro. Cyrille and Sylvain point out that “the cycle of melon de bourgogne on these lands is rather ‘Tardif’ and these parcels are often picked towards the end of the harvest.”

Esprit is grown on plots of similar age on more granitic bedrock, with gravel-silt topsoils. But, the brothers note, melon comes to ripeness much earlier here, so these plots are often picked from the first week of harvest.

Clisson, Epinay’s great vin de garde, hails from 2.5 hectares within the eponymous cru. Soils are gravel and silt over “granite de Clisson” bedrock. It is a warm, early-ripening site with vines planted more than a half-century ago. Harvests are pushed to optimal maturity, typically at least three weeks later than Sélection (“to be at the limit, just before the stage of overmaturity,” the brothers say) and yields are tightly delimited at 40 hl/ha to maximize terroir expression.

There is also a set of traditional method sparkling wines from chardonnay, pinot noir, cab franc and other varieties, all estate fruit, that bring a charming ease.

In the cellar

“Our cellar work is classic,” say Cyrille and Sylvain, meaning temperature-controlled spontaneous fermentations and sur lie aging in buried tanks. Lees aging is, of course, synonymous with Muscadet. Cyrille and Sylvain explain its importance: “Melon de bourgogne is an aromatically discrete variety, which expresses its differences only after aging on lees.” Yeast autolysis, they note, “protects the wine from oxidation and gives it a freshness and a characteristic beading, thanks to a significant presence of carbon dioxide.”

“In our region,” they continue, “the wine is stored underground in concrete tanks, the interior walls covered with glass or grès [a type of ceramic stoneware]. The tanks are a depth of 2 meters, the volume between 30 hl and 120 hl. They are accessed from the top through a hatch, through which we proceed to batonnage. We move the lees, which fall naturally by gravity to the bottom of the tank and are regularly resuspended in the wine, avoiding oxidation of the wines and preserving their aromatic freshness.”

The Sélection wines are bottled in the spring following harvest, preserving their vibrance and the characteristics of the gabbro terroir. Esprit stays on its lees for nine months without any racking.

For Clisson, Cyrille and Sylvain explain, “the juice is put directly in vats for a fermentation of two to three weeks. The wine is then racked and stays on its fine lees for nearly 36 months. It can ripen slowly and enrich itself on its deposit until it is bottled.” It is a powerful wine of character, with an intense and complex nose of acacia and quince, revealing the rich texture and fine balance of a great terroir of Muscadet on a relatively light alcoholic frame.

The traditional method sparkling wines are from base wines blended early in the winter following harvest and can vary slightly each year. The Blanc is typically a blend of 50% chardonnay, 35% folle blanche, and 15% pinot noir. The Rose is a blend of 60% pinot noir, 25% abouriou, and 15% cabernet franc.