“I feel an indissoluble connection with this place.” — Giovanni Messina

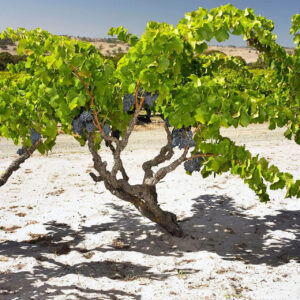

The vineyards of Vini Eudes command an enviable position on Etna’s eastern slopes: high above the thin strip of land that separates Sicily’s defining volcano from the Ionian Sea. Giovanni Messina and Laura Torrisi have staked their future on 3 hectares of native vines rooted in a once-abandoned property Giovanni grew up with. Sweeping stonewall terraces are banked into the sides of Monte Gorna, an offspring cone on Mother Etna, where the Eudes vineyards stand at 750-770 meters (2,460-2,525 feet) above sea level. Plantings of carricante and catarratto are just coming into their own at 12 years, but those familiar with the trajectory of Etna’s vines can anticipate a long, vital future. Altogether more ancient is Eudes’ parcel of ungrafted nerello mascalese vines, planted 100 to 130 years ago. Monte Gorna’s black sand and pumice soils are rich in potassium and minerals, poor in organic matter, and highly porous—ideal conditions for long, slow, healthy vine growth. Giovanni and Laura are committed to organic farming, hand harvests, and clean, temperature-controlled fermentations in stainless steel. The wines are polished, silky, and deep—a compelling expression of Etna terroir.

Origins

Eudes is a young venture, a pledge Giovanni and Laura have made to the land and a realization of their dreams. “This property belonged to a wealthy landowner who had abandoned it,” explains Giovanni. “In the late 1970s, my father fell in love with the place. Although his friends advised him not to buy, instead he did everything possible to find the owner and start negotiations for the purchase. After many attempts, he succeeded. By then, the buildings showed the passage of time and lack of care. Despite all, my father devoted himself to rebuilding the old farmhouses that dotted the property. As a boy, I followed my father during the reconstruction. After university, I decided to devote myself entirely to the realization of my father’s dream: the rebirth of places dedicated to viticulture.”

Monte Gorna

Sicily is Italy’s largest island by far—a compressed continent of diverse climates and terrain. Washed by three seas (Tyrrhenian, Ionian, and Mediterranean) and dominated by the towering form and unpredictable activity of Etna, Sicily gives a variety of wines that mirror this sweeping range of influences. Etna occupies a massive area on the island’s eastern side, with a base perimeter of about 135 km (77 miles). As a stratovolcano, it built itself layer upon layer from the seafloor to its present height of 3,350 meters (nearly 11,000 feet) above sea level over the past roughly half-million years. It is one of the world’s most active volcanoes, not just at its main craters, but also in and around myriad vents, fissures, and side cones. This has surfaced the mountain with an array of extrusive igneous rock and soil types—critically, all comparatively young and unweathered. As John Szabo writes in Volcanic Wines, even “the same volcano can erupt different lavas at different times due to changing composition in the magma below.” This means critical differences in proportions of silica, iron, magnesium, potassium, calcium, and sodium as well as rock structure from eruption to eruption, flow to flow. The sand, pumice, and ash that predominate on Etna are very poor in organic matter, giving vines what Szabo calls “a broad and balanced diet, but in small quantities.”

“The territory of the volcano has very different aspects of morphology and typology depending on altitude,” Giovanni explains. “Etna has four summit craters and about 300 adventitious cones on its flanks, all formed during their only eruption. There are several notable cones, but our focus is Mount Gorna, in the Trecastagni region. Since the end of the 1920s, throughout the Trecastagni, viticulture was very developed. Just think that the entire volcanic cone was completely cultivated, evidenced by the presence of ancient dry walls up to the summit of the volcano. Not all the plots were easy to run, but despite the difficulties, viticulture was the main element developed throughout the territory.” By the 1950s, when industrialization came to the island led the vineyards, including those on Monte Gorna, were largely abandoned.

Obviously, fortunes have shifted. In 2013, Etna gained recognition as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, in recognition of its “important terrestrial ecosystems including endemic flora and fauna and its [importance as] a natural laboratory for the study of ecological and biological processes”—not least of these, wine.

Climate wise, elevation and exposure are all important here. Eudes’ vineyards benefit from the brisk temperatures and marked diurnal shifts of these extreme altitudes. The Gulf of Catania and the wider Ionian Sea are not 10 km (6 miles) away. Exposure to the sea breezes further cools the vines and results in the steady accumulation of mineral substances such as sodium chloride that influence the salinity of the wines.

Giovanni Messina and Laura Torrisi

“Since I was five years old, I accompanied my father to our property on Monte Gorna,” Giovanni recalls. “It seems absurd to think a child could be fascinated by this ‘world.’ But I remember my initial happiness when work was still under way to recover the houses, and sheep came to graze. I even witnessed the birth of a lamb. Growing up, I felt more and more the need to recover a portion of the property where there was a small, ancient vineyard.”

Giovanni and Laura both studied at the University of Catania. “While we were studying, I decided—with Laura—to devote myself 360 degrees to Vini Eudes. Everyone was skeptical. Everyone except my father and Laura, who have supported me in the heaviest moments (and there have been many). But I am delighted with my choice. I have dedicated myself to a project of total recovery that I carry on now with the new plantings.”

Having studied political science at university, Giovanni recognized he would need the services of an expert in the vineyards. “From the beginning,” he says, “I looked for a worker who would treat the vines as if they were his own, a worker who was of the place and who knew the territory and the characteristics of the land. I found that in Angelo Buda. He is able to transfer important knowledge and secrets that the ancient peasants handed down from father to son.” One day, Giovanni may need rephrase this, as the Vini Eudes family now includes “our little girl, Alice, born the day we bottled the 2016 vintage.”

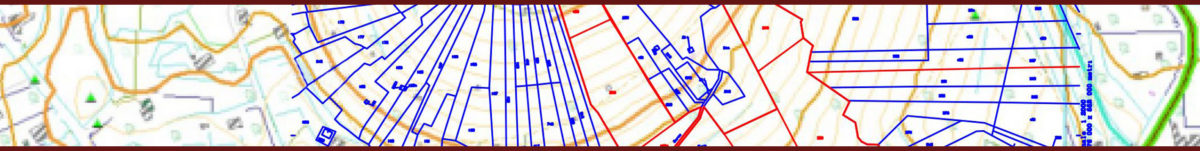

Vineyards and farming

“The peculiarity of Etna rests in the diversity of the land,” Giovanni asserts. “For this reason, the Etna territory is divided into Contrade, or subzones. We are located in Contrada Monte Gorna. Here, even within the same vineyard, we find varying soil compositions and mineral content. The vineyard from which Bianco di Monte comes is very stony, rich in minerals, pumice skeleton, and trace elements, including iron, copper, and silica. A peculiar characteristic of the soil is its intensely dark color. In the parcel from which we produce Monte, the composition is very different: mostly sandy. The earth is highly porous, driving the roots in search of moisture and nutrients.”

The Eudes vineyards reveal two faces of Etna viticulture today: an ancient parcel of 100- to 130-year-old nerello mascalese vines shares the property with carricante and catarratto vines planted in 2007. In both, Giovanni believes the key is “to carry on the traditions that our territory was slowly abandoning.” In keeping with this philosophy, farming is organic. “We are careful not to use anything that is not natural, in full respect of the terroir.” Harvests are all by hand.

In the cellar

“Our philosophy is to respect how much the vineyard has given us and to produce typical Etna wines. Once the grapes arrive in the cellar, they are gently pressed and the must fermented in temperature-controlled stainless steel tanks.” Post fermentation, Bianco di Monte is racked into stainless steel; monovarietal carricante Monte into oak cask. A minimal dose of SO2 and temperature control block malo to give full expression to the mountain freshness of the wines. Both see 15 months of elevage on the fine lees with simple batonnage. After light filtration, the wines are bottled when “they have naturally reached a point of stability,” explains Giovanni. They age a further eight months before release. “The main characteristic of our wine is without doubt the great minerality,” Giovanni believes, “An Etna wine should be especially recognizable: a strong sensation of sapidity linked to a pleasant persistence of acidity.”