“I see the strengths of German wine as the finesse, depth, minerality, and precision of its aromas.” — Markus Spindler

In 1620, Sontag Spindler left Burgundy for the Pfalz — just as the Thirty Years War was making this a uniquely inauspicious time to resettle in the Palatinate. Almost impossibly, Spindler took the long view. He began to purchase vineyards and by the war’s end was able to acquire one of Germany’s most revered parcels, the Kirchenstück. In 1828, Spindler’s foresight was confirmed when this site was assessed at the highest tax rate in the land. But Napoleonic law splintered Spindler’s descendants’ holdings and the estate was evenly divided among three brothers. Since that time, Weingut Heinrich Spindler has taken its place among the great estates of Forst, with parcels in the Jesuitengarten, Pechstein, and Ungeheuer. None of this is lost on Markus Spindler, great-grandson of Heinrich. He carries forward the 20-hectare, certified organic estate with a level of skill and respect equal to the heritage and holdings entrusted to him. From his everyday bottlings to his top riesling crus, the wines are tactile, focused, detailed, and decidedly dry. They are about nuance and purity over power, grace and precision over opulence. Above all, they are meticulously wrought portraits of legendary terroir.

Region

With a startlingly Mediterranean climate, palm, fig, and citrus trees flourish alongside a wide range of grape varieties in the Pfalz. In and around the village of Forst, however, riesling reigns supreme. Here, a narrow swath of gentle south and east facing slopes rises behind the village to meet the Palatinate Forest, part of the largest contiguous woodland area in Western Europe and a designated UNESCO biosphere reserve. The Haardt Mountains, an extension of Alsace’s Vosges, shelter the vineyards from cold and curtain them from rain.

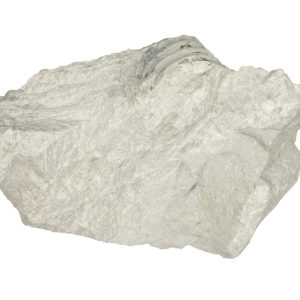

Forst’s top vineyards — Markus is blessed with tiny parcels in each — are some 120 to 150 meters [390 to 490 feet] above sea level, benefitting from morning sun and rising breezes. The sites are distinguished by their varying microclimates and soil compositions: colored sandstone, shell limestone, and basalt — deep, layered, and rich enough in clay to protect vines from hydric stress in this very warm, very dry region.

Colored sandstone defines the Pfalz, from the great red and yellow blocks of it that form the walls of Speyer Cathedral to the soils of the Mittelhaardt. The sandstone was formed some 250 million years ago, when ancient rivers laid down their sediment in a then desert-like landscape. Oxidized iron accounts for the red variant; thermal waters that washed out the iron account for the yellow.

Forst’s least expected feature is its outcrop of basalt. We can’t exactly call the Pfalz a volcanic region, but when the Rhine valley collapsed some 50 million years ago, magma was forced to the surface and cooled to produce black basalt stone. Basalt is a notable component of several sites here, most crucially Pechstein. Forst’s growers haven’t left it entirely to nature to distribute this prized element, though. For centuries, they’ve collected, then scattered basalt shards through their vineyards to help retain heat and capture the opulence and smoky salinity basalt can impart to riesling.

Although Forst’s vineyards seem predestined for riesling, until the early to mid-20th century, these sites (as with the rest of Germany) were largely planted as field blends. But, according to Markus, in Forst, the percentages of other varieties, mostly silvaner and gewürztraminer, were uncommonly low and by the 20th century, riesling was varietally labeled. More recently, sauvignon blanc has also made its mark on the region and Markus takes it every bit as seriously as his riesling.

Winemaker

Family life is the heart of the winery, where Markus and his wife, Lola, live with their three young children. Aside from family outings in the Pfalz Forest, Markus’ passion is for Alpine sports – climbing, mountaineering, and biking – which, he says, comes from his grandfather. “Beyond that, nature is very important to me. I draw a great deal of energy from it.”

Markus wasn’t always sure he wanted the life his ancestry indicated for him. In 1996, he started off with apprenticeships close to home at Dr. Deinhard (now von Winning) and Friedrich Becker, and in the Saar with the legendary Egon Müller. He went on to fulfill a civil service tour, then did a year-long stage at Schug in Sonoma. Putting some time and space between him and the family estate gave Markus perspective: “I needed the distance to realize what a treasure we have at home.” He returned to Germany and enrolled in the country’s top wine school, Geisenheim. “I have always been fascinated by the aging potential of the riesling grape. So I asked the wine chemistry department if I could do my thesis in this area. This led to a study of approximately 30 wines from eight vintages, with particular emphasis on the analysis of volatile aromatic compounds.” He also undertook further apprenticeships, most notably with F.X. Pichler in the Wachau.

In 2007, he graduated and returned to Forst, to work alongside his father, Hans. Eleven years later, Markus took full responsibility for the estate, which includes a well-regarded Gutsausschank (“like a taproom, but for wine,” Markus modestly translates) in which his brother Florian’s acclaimed cooking is matched with bottles from the Spindler cellar.

Vineyards and farming

To walk the Spindler parcels is to hear the echo of history and feel the power of terroir. It is best to start with the Kirchenstück, a 3.7 hectare clos directly behind the village church (Kirche); of which, Markus has a 0.28 hectare sliver. The low sandstone walls around it absorb the sun’s warmth and gradually release it at night, gathering warmth and ensuring air movement that safeguards the vines from frost. The soils here are sandstone scree, sandy clay, and basalt, all planted strictly to riesling. The best wines from the Kirchenstück are a dialectic of finesse and complexity, elegance and power, succulence and structure.

The origins of the name Ungeheuer (“monstrous” in English) have long been debated, but Markus cites the most convincing: “The vineyard was first mentioned in official documents in 1470, as the ‘an dem Ungehuwern.’ In the parlance of the time, this referred to the ‘unsettled and unsettling’ nature of this area west of Forst.” Wild no longer, this vineyard rests on a wide range of soils, dominated by clay and limestone. It is one of the largest Forst sites as well as one of the driest and warmest, but thanks to a significant proportion of deep clay, vines stay cool and hydrated. Markus has a choice 1.5 hectares in a steeper, limestone reef section. “Cool air flows in nightly from the woods,” Markus explains, “extending the ripening period for the grapes and boosting aromatic development.”

The Spindlers have under a hectare in the vineyard that, as Markus says, “riesling lovers love”: Pechstein. The name means “pitch stone,” referring to the basalt in this 17-hectare site, which translates into rieslings of density, with an unmissable smoky-salty intensity. There is a phenolic component — “like quince or grapefruit” — to the rieslings grown here, but they are “always clear and deep in their minerality,” Markus notes.

According to the famed 1828 tax classification, the second-best site in the Pfalz is the little Jesuitengarten. Here Markus has just 0.26 hectares on rich loam, colored sandstone, and basalt. A slate layer ensures a healthy channeling of water from the mountains to this site.

Markus regards the 8.6-hectare Musenhang as “one of the best vineyards of this category,” an Erste rather than Grosse Lage. He has a 0.33 hectare slice that he prizes for “its cooler microclimate, strongly influenced by the nearby forest, where ripeness is good but never excessive, and where limestone soils show more structure and minerality.”

The Spindlers have been committed to farming without herbicides, pesticides, or synthetic fertilizers for nearly 20 years. Markus officially converted to organic viticulture in 2012, an easy and natural transition as all the groundwork had already been laid by his father.

“I think if you want to make top-level wines with character, the basis is healthy soil with a great variety of microorganisms, insects, and a high humus. It’s important to me to have an ecosystem in my vineyards with variety, both above and below the soil,” Markus explains. “Homemade compost, diverse cover crops, and strictly biological plant management techniques are essential for us. Our intensive use of compost — including pomace, straw, and horse manure — allows us to deal with heat and drought when they come.”

Markus is responding to climate change with more sensitive canopy management, removing leaves only on the north side of the plant, and making a very thoughtful, focused use of cover crops. “This is really important,” he notes. “We have a mix of 50 different crops to give the soil a nice structure and to protect it from tractor compaction. We only cover every other row due to competition for water and mow the cover crops only in case of drought.”

All the top sites are hand harvested with multiple pickings.

In the cellar

Markus’s highest objective — “to make wine with filigree depth” — may sound like a paradox. But it is that tension that makes the wines so arresting. “In the vinification, we use maceration, skin fermentation, native yeasts, battonage and new wood. However, we approach all of these enological steps with Fingerspitzengefühl” he says, using a German term that encompasses instinct and touch. “Precision, minerality, and fruit character are not to be lost.”

Not surprisingly for someone who wrote his thesis on the evolution of aromatics in aging rieslings, Markus sees his greatest challenge in the cellar as “preserving the full range of natural aromas.” To achieve this, grapes are pressed gently, at low pressure, with limited use of pumps and maximal reliance on gravity. Macerations are short, fermentations start with ambient yeast, though cultured yeast may be added to ensure the rieslings finish fully dry. Markus prefers long, cool ferments in stainless steel and neutral Stück (1200L) and Doppelstück (2400L) oak casks. The wines remain on the fine lees, with occasional batonnage, until they are bottled between February and June after harvest. Attention to every facet of the process is obvious from the everyday estate riesling, sourced from holdings in and around Forst, to the arresting and expressive single vineyards. While his village-level Forster Riesling is raised in 80% stainless, 20% neutral cask, the single vineyards vary, dependent on site, but tend to be fermented and raised entirely in stainless, again with the emphasis on capturing the panoply of nuanced aromas. Markus wants his sauvignon blancs to be of a drinkable, fruit-driven style. “By staggering the harvest in various stages of ripeness, we get a sauvignon blanc of complexity and variation, on the one hand with green, very fresh aromas, and on the other, ripe, complex fruit, leading to an incisive wine of structure and length.”