“There’s a change coming. Württemberg is getting more and more interesting. We’re right in the middle of it.”

Moritz Haidle makes for an unconventional traditionalist. As a freestyle rapper and graffiti artist, he cuts a radical figure in the Swabian wine scene. But he’s also fiercely proud of the heritage behind his family’s estate and the Remstal valley he calls home. He’s fearless (and tireless!) in his reimagining and refining the potential of both. In the near-decade since he took over, he has made his mark many times over by combining a background of serious training under flagship German producers with the intuitive confidence you’d expect of an artist. Vintage after vintage, and most notably with the conversion first to organics and then to Demeter-certified biodynamics, the wines have gained focus and expression. Across the board, they articulate the character of the Haidles’ enviable collection of single vineyards, the striking cool climate and diversity of soils that mark out the Remstal as one of Germany’s most fascinating, under-the-radar scenes.

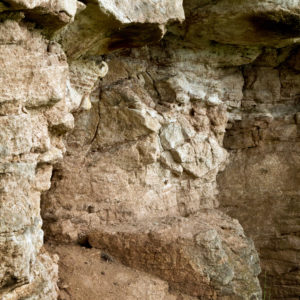

Weingut Karl Haidle is the oldest private winery in the Remstal. Co-ops have a deep tradition in the area and Moritz’s grandfather, Karl, was a pioneer in making and selling his own wines, starting in 1949. Moritz’s work to pare down Württemberg’s long, winding history to a succinct story honors that tradition. The estate specializes in structured, elegant, mineral-driven Rieslings, with 50% of its vineyards planted to the grape. This work starts in ancient dry-wall terraces of Riesling vines, some own-rooted, that rise from just behind the cellar to meet the scenic ruins of a fortress. Moritz has made it his mission to restore meaning to the Remstal’s historic grand cru, the Pulvermächer, and direct attention to sites of serious potential like Berge, Burghalde, Mönchberg, and Häder.

White wines remain the anomaly in Württemberg. Those hunting for excellent Blaufränkisch (aka Lemberger) can stop their search here. The Haidle Lembergers are high-toned, complex, and savory, channeling the interplay of clay-rich soils, exceptional vine material, and deft cellar work. Their Trollinger “Alte Reben” takes Swabia’s signature chillable red to the next level — a far cry from the cheap and cheerful Trollis that diluted the region’s reputation decades ago.

Moritz’s wines embody the energy, creativity, and vision he brings to everything he touches. From his literal calling card Riesling “Ritzling,” graffitied with a design by Moritz himself, to what he calls his first “mainstream natural wine,” a Kerner that honors his family’s early adoption of the variety while playing with its affinity for maceration, his wines are blend work and play deliciously.

Across the board, his constant fine-tuning in the cellar, particularly the ever more specific micro-vinifications that enable him to drill deeper into the character of old vines, soil types, and microclimates, is paying off. The wines are totally vibrant, unified by a lipsmacking savor and salinity.

History

“It all started with this house,” Moritz explains, pointing to a handsome, window-boxed building right in the middle of town. “My family moved in in 1869. We don’t have a long tradition like in the Mosel. So the first Haidle living here was a shoemaker. But it was normal that everyone had a few vineyards.” The winery got its start 80 years later. Moritz’s grandfather, Olympic-caliber gymnast Karl Haidle, had a single hectare of vines. He began vinifying his own grapes, and launched a negociant business alongside it. Then his son, Hans – who grew the estate from 2.5 to its current 23 hectares – and now Moritz have led the way in elevating Württemberg’s reputation. It’s still very much a family business. Hans plays a consulting role, Moritz’s mother and sisters are involved in running many key operations. That back-and-forth among the generations builds on ties to the past, but also gives Moritz a supportive springboard from which to launch new ideas.

Vineyards and Farming

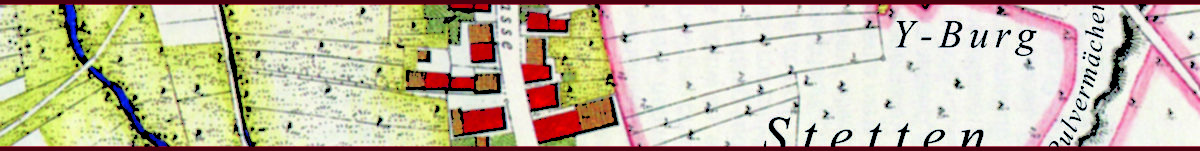

The Haidles hold an enviable collection of vineyards clustered in and around the historic wine villages of Stetten and Schnaitt, just 6 kilometers from each other. Stetten is cooler, the wines that much more focused, mineral, and saline — “what Stetten Riesling is all about,” Moritz notes. Before vineyard reformation rolled through the area, all of Stetten’s major vineyards were terraced. Today, scattered vestiges remain and the Haidles are stewards of a half hectare them in the Stettener Pulvermächer.

The Pulvermächer (this is a German word you’ll want to learn to pronounce correctly so you can ask for it by name: PULL-ver-mek-ker) is the Remstal’s pride. First documented in 1420, this vineyard crowns a steep south/southwest-facing, 360 m.a.s.l. hill. The Haidle’s parcel of ancient vines is gap-toothed, the rows too tight for a regular tractor. But Moritz refuses to change anything. “No other Riesling has the saltiness of the Pulvermächer.”

Sites in Schnaitt, by contrast, give warmer, golden Rieslings on the rich, savory side. The Lembergers spring from parcels in both villages as well. The pair we offer hail from Stetten, with the Häder a high (330 m.a.s.l.), cool site on keuper soils, and the Berge a smaller parcel from the village’s southern edge.

Moritz sums up the viticultural focus at the estate simply: “We want to work with nature to get long-lasting vines with deep roots and naturally low yields.” In 2020, at the urging of the estate’s long-time vineyard manager, Weingut Haidle sought and earned Demeter biodynamic certification. Standing in the old terraces, where mint and wild herbs create a cover crop that’s as fragrant as it is verdant, it’s clear this approach is restoring balance to a delicate ecosystem that includes human cultivation over centuries.

In the cellar

The winery is organized to move the wines via gravity. Fermentations are spontaneous, the whites undergo extended lees contact, nothing is fined, and the wines are bottled with just a touch of sulfur. Pride of place goes to a collection of custom-carved casks, some of which are 70+ years old. “I swear by the old barrels of my grandfather,” Moritz says. Almost all of the Rieslings are raised in large neutral oak now. Even the entry level “Ritzling” sees time in mostly old oak barrels.

Single-vineyard Rieslings are whole-cluster pressed in a smaller press. In 2020, Moritz started to vinify every parcel individually “to get to know the terroir better.” Despite shifts in fashion, Moritz still thinks “barriques are best for Lemberger – it gives me more possibilities to work with different barrel makers, and we are using mainly neutral oak anyway so size is more important when it comes to microoxygenation.” He now makes all the reds except Trollinger in small French oak.